Creativity is the singing of the soul. When we create, we draw from the deepest parts of who we are and express ourselves to the world. The act of creation, drawing forth and connecting to our inner selves, is the joy involved in creativity. Having something nice in the end, to me, seems like a bonus! I believe this act of channeling the awen is not only inherently spiritual, it is also part of what it means to be human. But to allow our souls to really sing, we have to grow comfortable with what we create, we have to set aside our judgment, and to grow our skills as bards.

Last week, I explored what the bardic arts are, the cultural challenges associated with the bardic arts, and some ways community groups circumvent said challenges. We looked at the creative spirit of children, and how that spirit gets repressed by cultural challenges and the language of disempowerment. We looked at the ways that we think about “talent” and “creativity” serve to severely disempower us from pursuing the joy that is the bardic arts. Now that we have some sense of what has prevented more people from engaging in their creative and human gifts, we can now turn toward answering the two questions I posed last week:

- How can we make the bardic arts accessible to every person?

- How can you begin to take up a bardic art yourself, regardless of skill level?

Last week, I also established four broad categories of bardic arts, which we’ll be returning to in this post:

- Performing arts: including music, theater, dance, movement, storytelling, singing, acting, and so on.

- Fine arts: including painting, sculpture, drawing, photography, printmaking, and so on.

- Literary arts: including writing poetry, songwriting, writing prose, and any kind of writing that requires craft and skill

- Fine crafts: including fiber arts, metalwork/smithing, pottery, glasswork, woodwork, bookbinding, papermaking, and so on.

And with that background, let’s begin to answer the two questions above and move into a place of empowerment, creativity, and the flowing of awen!

The Triad of Bardic Development: Exposure, Technique, and Practice

In the same way that the ancient bards were dedicated to their craft and in the same way that children devote countless hours to their own creative expressions, so, too, do we need to carefully cultivate our modern bardic arts if we are to grow our gifts. I’ll use myself as an example here of how we might cultivate the bardic arts.

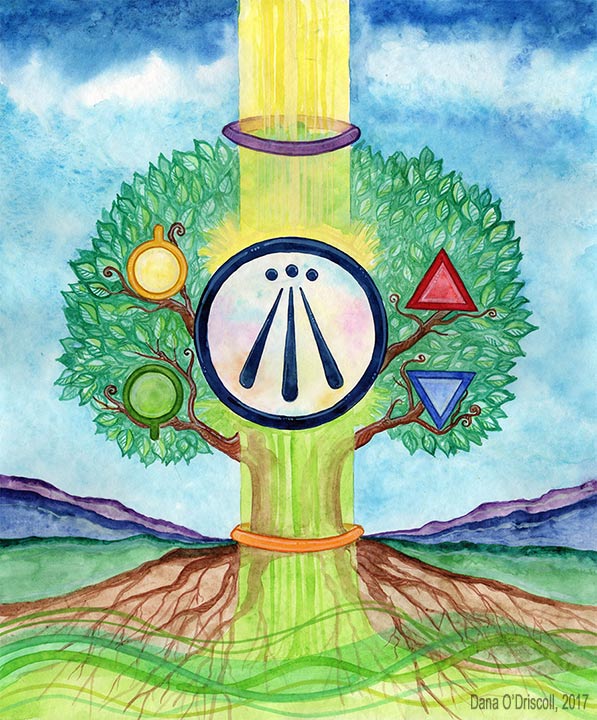

I have been a visual artist focusing on the theme of trees and whimsical nature art and have been seriously pursuing this work for over a decade. As part of my own development as an artist, I often go to the natural world for inspiration and observation: studying the patterns of leaves, sketching in the woods, taking photographs, and bringing that inspiration back into my art studio. I also regularly expose myself to the work of others who are using different artistic techniques (talking with them, viewing artwork, reading books on techniques). I go to museums and study, in detail, various watercolor paintings. I talk to watercolor artists about their own styles and process and inspiration. We share work with each other and ask about techniques. Regardless of how “good” I have become, I regularly take classes, read books, and watch youtube tutorials, which helps me gain the theories and techniques of a visual artist. Often, as part of these classes, I get expert feedback on how to improve my work. Finally, I practice my art as often as possible, several times a week (often for several hours), in a space dedicated for this purpose. Practice doesn’t just mean do the same artwork over and over, but rather, I regularly take on new challenging subjects and new media so that I can continue to grow as an artist. This might mean that I don’t always succeed, but there is much value in the practice.

In fact, the way that I develop my skill as a visual artist is no different than the Jazz musician who practices his scales each day, or the aspiring poet who memorizes large chunks of others’ poetry, or woodworker who hones her skills. And this is important: there are things that you can do, regardless of what skill level you begin at, that will help you make good progress on whatever bardic art you choose to undertake. Further, from my example above, we can see that there are at least three essential paths toward developing bardic skills:

The first path of the aspiring bard is immersing yourself in the thing you wish to master. You have to expose yourself in the world of that particular bardic art and begin to understand how others are already working on that bardic art. How this path manifests depends on the broad genre of bardic arts:

- Visual: Visual artists cultivate keen observation skills (of the subject matter) and also expose themselves to others’ artwork.

- Literary: Literary artists read copious amounts of others’ work; for poets this may include memorization of others’ poetry and forms.

- Performance: A performer would attend many performances and observe other performers practicing their art.

- Craft: A craftsperson would study as much of the craft of others as possible. For example, a leatherworker would study other people’s leather working techniques and finished products, and so on.

The second path of the aspiring bard is to learn and practice the techniques of your art/craft. Each bardic art has a set of theories and techniques that you need to understand in order to develop proficiency and eventual mastery. Studying these theories and techniques (on your own and/or through others’ instruction) can greatly assist you as an aspiring bard. Specific bardic arts have their own techniques and their own tools, some of which are listed here:

- Visual: Techniques using particular artistic tools, understanding perspective and distance, understanding light/shading, understanding color theory, understanding how paint blends on a page, etc.

- Literary: Understanding the structure of a story; studying rhyme, studying different forms of poetry, building vocabulary, studying syntax

- Performance: The technical aspects of dance (how to safely perform different moves), how to engage an audience, the technical aspects of acting, singing, vibrato, positioning, lighting a space, etc.

- Craft: Technical aspects of the craft, for example, in leatherworking it would be cutting leather, using leather tools, dying and staining leather, finishing, putting pieces together, designing patterns, knowing which kinds of leathers to use for which projects. Each craft has its own techniques.

Some techniques may transfer from bardic art to bardic art, while others need to be learned anew. For example, drawing skill helps me not only as a painter, but also as a leatherworker when I’m designing and creating leather tooled pieces. But that drawing skill is not so helpful when I’m trying to tell stories around the fire!

Practicing the techniques for some bardic arts also requires the tools: for example, as a watercolor artist, I need, at minimum, high quality brushes of various sizes, watercolor paper of a good quality, and a nice set of watercolor paints. Working with sub-par tools leads to a sub-par experience. Having better tools offers me a better “starting point” and eliminates certain kinds of struggles.

The third path of the aspiring bard is dedication and regular practice. Each bardic art requires dedication and practice, at minimum, on weekly level. Remember that practice often includes many things that are never seen by an audience (sketches, practicing the tale in front of the mirror, practice scraps of leather discarded, scales upon scales on an instrument, etc.). And because these things are hidden, we forget that they are ever done. However, dedication and practice are the only way we can achieve any form of proficiency, much less mastery. We don’t get good at something by thinking about it–we get good at it through practice (people seem to understand this with musical instruments but with little else!)

A second critical aspect of practice is that different kinds of practices are necessary to achieve proficiency. Sometimes, practicing the same thing over and over gives you a lot of skill doing that particular thing, so that you achieve mastery. So, if you make 100 leather bags, your 100th one will be much better than your first. But at some point, there is a diminishing return to continuing to practice the same thing–you’ll get to a certain point and not be able to go any further. It is for this reason that we also need challenges and exposure to more difficult kinds of practice.

A challenging piece/performance requires you to gain new skills, to push your skills a bit beyond what you can handle, and encourages new growth. With challenge is the possibility of failure, but failure is not something to fear. Failure is a regular and consistent part of the learning process, and all proficient people practicing any bardic art have had their share of failure. How we handle failure here is key–letting failure be an opportunity to learn, rather than an opportunity to shut down, is critical to our own development (for more info, see Carol Dweck’s TED talk and research on mindsets. Dweck’s work explores two mindsets for approaching failure–when we can learn and grow, we gain much. But when we shut down and fear/avoid failure, developmentally, little growth happens). A common saying is that the master has failed more times than the novice has even tried, and this is a very true of the bardic arts. In this view, as we cultivate our bardic art, we must also cultivate the understanding and openness that is required for long-term growth and success. Embrace failures as part of learning and for the value that they offer. Of course it is frustrating to make a mistake, but mistakes are a sign of growth because you are pushing yourself beyond your comfort zone.

My father and mother offered powerful lessons to me concerning mistakes and failure when I was a small child learning painting. I remember working on a piece very hard, only to have a huge paint drip go into the middle of the sky. I was ready to cry. My father stopped what he was doing, and came over to me, and showed me how to turn that paint drip into a colorful cloud. He told me that mistakes were an opportunity to try something unplanned, something different, and that some of his best work had been a result of such a mistake. When this happened again, my mother reinforced the lesson several weeks later. As I continue to learn new things, I am always appreciative of that lesson and what it taught me.

And so, is through the triad of exposure, technique, and practice that we can develop proficiency, an eventual mastery, in the bardic arts. Notice that “talent” is not on this list. Anyone, given enough of the triad above, can develop at least a basic proficiency in a bardic art of their choice. Talent might help speed things along, but it is is not necessary. If the purpose of the bardic art is the process, the journey, the ability to connect with our hearts and spirits, then the end result seems but a secondary consideration.

Developing a Community and Culture of Bardic Arts

What may not be immediately obvious to the aspiring bard is that the triad above is embedded in a broader culture of bardic arts and also embedded in a specific community of practice. Bards need a community to share their work, talk to others about their work, to receive feedback, and to share their bardic gifts. Each community of bards has their specific techniques and tools, practices that are unique to that community. Further, a bard is often incomplete without an audience of some kind, whether that is the reader of a text, the audience of a performance, the viewer of an artistic creation, or the user/receiver of a craft.

In the same way that bards need communities in order to develop effectively, so, too do communities need bards. We cannot rebuild the bardic arts on an individual level without also rebuilding the communities in which these bardic arts are shared. Those engaged in the bardic arts need to feel needed; as though their work is important and it matters. Because it does. And so, we have to recognize that our communities are richer and better with our bards present and being bards. Imagine sitting around a fire at night with a dozen or so people—the more of those people engaging and sharing their bardic arts, the more interesting of an evening is shared by all. If nobody has a bardic art to share, the community suffers (and the evening is dull). This, too, is supported by learning research: we know that when people join communities of practice (see, for example, the work of Wegner and colleagues), those communities strongly support overall development in a particular skill.

And so, the questions that remain to us now are: How do we build communities without inhibitions against the bardic arts? How do we nature and support people in those communities?

Children. As mentioned in last week’s post, children are natural bards, and the first thing we can do in terms of cultivating communities of bardic arts in the long term is to let children be children and to help them retain and cultivate their creative gifts. Children should be free to create, explore, make messes, make music, and collaborate with friends. As parents and loved ones, finding ways of supporting, reinforcing, and cultivating their creative gifts should be encouraged, especially to help provide a balance to mass education systems which discourage creative expression and creative thinking. As children grow up, they should be encouraged to continue to pursue whatever bardic arts inspire them. They should also be encouraged to view mistakes as an opportunity for growth (which, according to some of the research I included above, is a very teachable thing). These children, then, can grow up to help lead bardic communities of the future.

Adolescents and Adults. In terms of the adolescents and adults, some remediation likely needs to be in order, based on the cultural and educational disempowerment so prevalent today. The overall goal is to help adolescents and adults take down their barriers and inhibitions and reconnect to their creativity in the spirit of the freedom children have but tempered by the focus and ability of an older generation.

First, adults/adolescents must have opportunities in their material and social contexts for practicing their bardic arts, in the same way that children have. For example, storytelling is a common thing that can be practiced daily. Children are constantly telling stories to each other and to their families. Adults could cultivate the same opportunity. For example, perhaps each member of the family around the dinner table tells the story of their day as part of that meal. This simple family ritual allows for the building of a storytelling culture within a family and gives each opportunity to learn to be a storyteller. The same can be true of many other bardic arts: creating social opportunities for bardic arts to be shared and practiced is an important part of cultivating them. Another option here is the Druid’s Eisteddfod, a circle of bardic arts around the fire.

The second thing, also tied to children and creativity, is the fostering of “play time”, that is, unstructured leisure time in which to explore and engage in the bardic arts. As with children’s play, at least some time should not be dedicated to accomplishing a particular task, but simply exploring materials, techniques, and enjoying the process of figuring things out. (This, of course, means we have to reconsider our own relationship with time and make time for these things, which ties directly to my earlier series on “Slowing down the Druid Way.”)

The third thing adults/adolescents need is the tools to engage in the bardic art and access to expertise. Tools can be procured usually fairly directly (a materialist culture lends itself well to such a thing), but expertise might be much harder to come by. Given that, I encourage those interested in a particular art to seek out a local community, or, online community if no local one is present. These things can be learned on one’s own, but it is often more effective to learn from another. Chances are, anyone who has developed mastery in a bardic art has had plenty of mishaps and mistakes along the way, and its useful to talk about those mistakes as much as it is to talk about the successes!

The fourth thing is to reframe our language within that community of practice. Aspiring bards need both support as well as constructive feedback, and the challenge in a community is finding methods of doing both in ways that nurture the overall development. Some communities offer competitions or critique days that allow people to seek feedback to improve their work. These structured forms of critique and feedback are generally a safe space for those who want that kind of feedback.

For Aspiring Bards

And so, now we’ve come to it–how do I begin to take up the path of the bard? Here are two questions to get you started:

Which of the many bardic arts (visual, performance, literary, or craft) seem interesting to you?

Select something that appeals to you, that is interesting to you and that inspires you. Find one that sings to your soul. Don’t worry about whether or not you can or can’t do this thing or if you know anyone else who does it—all bardic arts take dedication and work. Try it out for a bit making sure that you have given the practice enough time to get past the very beginning difficult beginner parts. I’d suggest spending a minimum of 20 hours on it over a period of time to see if it fits you well (this is the practice we use in the AODA curriculum and it works tremendously well). Twenty hours is enough to know if you will enjoy it, it is enough time to have some small successes, and it is enough time to get past the 10 or so frustrating hours (or more) of learning where not much is accomplished. If this bardic art turns out not to be a good fit for you, try something else until you find your right fit. In this process of exploration, you might borrow the necessary tools/equipment for practicing the art rather than buy them to minimize financial investment until you are sure you will pursue this particular bardic art.

Where is there a community with whom you can connect?

Seek out a community that is engaging in the same bardic art that you have interest in. Once you find that community, show up. I strongly advocate for finding a physical community of people who are engaged in your bardic art (or a range of bardic arts) that you can share with. This community should meet regularly (1/month, at minimum). If you can’t find a community, consider starting one (ask friends to come over once a week and play music or share stories by the fire, etc.). Online communities are a way to supplement local communities, but we encourage you to not stop at online communities. Online communities that have some physical component (e.g. art that is traded through the mail, performances that are given, in-person conferences that are present) are much more effective.

The Flow of Awen

The Ancient Druids understood that the flow of awen, the divine spark of creativity or inspiration, was a magical thing (and a topic I talked about in depth several weeks ago). And the Ancient Druids weren’t the only ones to recognize this sensation: many cultures recognize a muse or deity that is associated with creativity (the Greek Muses; Sarasvati, Hindu Goddess of the Arts; Hi’aika, Hawaiian Goddess of Dance/Chant; and so on). Whether you see the awen as a kind of abstract power or something that comes from a diety, the idea is that this creativity flows through a person when he or she is engaged in her bardic art. Perhaps you’ve experienced this yourself: it is a powerful sensation.

Personally, I see awen a lot like the flow of a river. If you are opening up those channels for the first time, it is like water pouring into an area: the river will need to make work to flow effectively; there might be obstructions to work through, and so on. But the longer the water flows in that spot, the more effectively it can flow and the more channels the water makes. Expressing creativity and channeling the flow of awen is a lot like using a muscle—it can atrophy if it is not used. And yet, any muscle can be brought back into health with enough practice; you might see this like a kind of “bardic therapy.”

This is where everything in this post comes in: we need tools, practice, and skill to allow the awen to flow through our lives and inspire us. And when we are in a place with our own skills and abilities as a bard, the awen can flow strong and we can create incredible works. We need the basic skills and approaches so that we can forget about the technical details and instead just let the awen flow. It is once we’ve achieved a certain level that we can really let loose, let our subconscious and muscle memory take over, and just flow with the awen. The things outlined in this post can help the awen flow into your life permanently and powerfully.

May the awen flow within you in your pursuit of the bardic path!

Reblogged this on The Dreaming Path.

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Very inspiring post, dear Dana! Thank you & much inspiration on your craft way!

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thanks for reading and for the comment! You are most welcome.

Reblogged this on Rattiesforeverworldpresscom.

I don’t draw or perform but I do design and plant gardens to honor the Ancestors and my patron Goddesses, and for the Nature Spirits. I use trees, plants, flowers, colors, and objects that I feel will best show love, have some symbolic meaning, or to welcome certain Spirits to my gardens. These are all offerings made with the art form I express myself in best. Niniann Lacasse

Wondering about the design arts, esp. environmental/landscape/agricultural?

Yes, for sure. I totally consider garden design and cultivation as a visual art! There is this conservatory in Pittsburgh called Phipps Conservatory. It has rooms of flowers cultivated to look just like impressionistic paintings! It is incredible 🙂