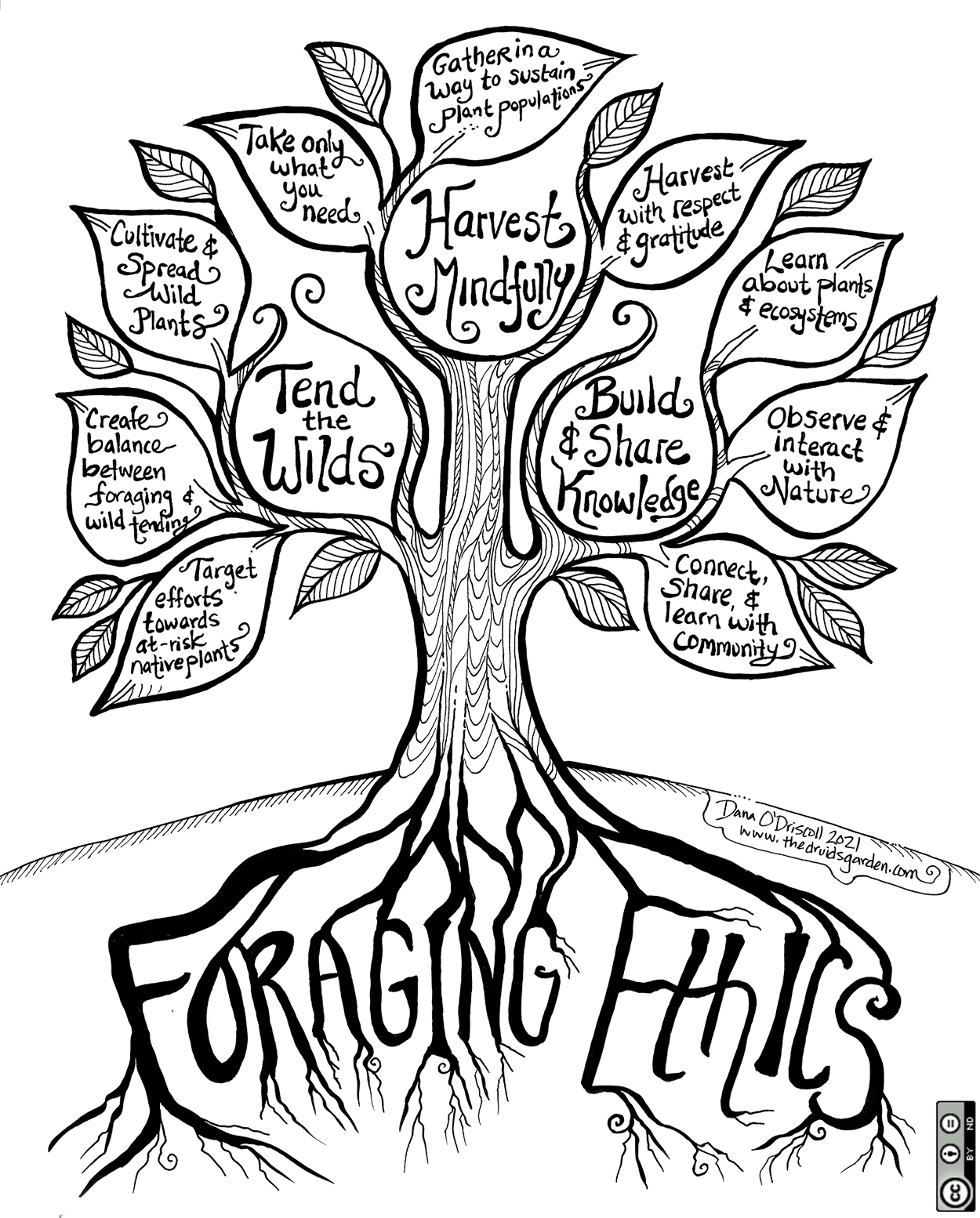

Foraging for wild foods, mushrooms, and wild medicines is something that is growing as a pastime for many people. The joy of foraging from the land connects us to our ancient and primal roots and allows us a chance to build a more direct connection with nature. But with any practice rooted in nature comes the need for balance and responsibility. Thus, the following principles can help wild food foragers and wild food instructors harvest ethically, sustainably, and in a way that builds wild food populations rather than reduces them. I share both the principles in text below as well as graphics. The graphics are (full size and web-sharable versions, see links) and they are licensed under a Creative Commons license. Anyone who teaches plant walks or wants to use them in foraging, wild foods, and herbalism practice is free to download them, print them, and share them! The two graphics are of the same content, rendered differently. For full size printable versions click the following links: The Foraging Flower (8 1/2 x 11″ JPG); Foraging Ethics Tree (8 1/2 x 11″ JPG)

Harvest Mindfully: Mindfully and ethically harvesting from the land to ensure sustainable harvesting, ensuring the long-term survival of wild food and medicines for the benefit of all life and future generations.

- Take only what you need. Harvest only what you need and resist the urge to harvest everything. Find ways of preserving foods and wild medicine so that nothing goes to waste.

- Harvest in a way that sustains long-term populations. Be careful about how much you harvest, where you harvest, and when you harvest to ensure that you are not damaging plant populations or harming individual plants. If you need to take a root harvest, it should only be done sustainably and when plants are in abundance. If you are taking a mushroom harvest, remember that mushrooms are the reproductive system; if you harvest them all, the mushroom can’t reproduce. At the same time, recognize that some plants should be harvested as much as possible–those who are spreading and harming native plant populations.

- Harvest with gratitude and respect. recognize the gift that nature is offering you, and harvest respectfully and with gratitude. Be thankful for the plant and the opportunity to harvest.

Tend the Wilds: Our ancient human ancestors understood that creating a reciprocal relationship with nature were the only way to ensure a more bountiful harvest and sustain our lands so that they could sustain us in return. Thus, building in wildtending practices and tending the wilds should be a counter-practice to foraging.

- Cultivate and spread wild plants. Learn how to cultivate and tend the native and naturalized plants you commonly harvest. Work to establish new wild patches of these plants by gathering and scattering seeds, dividing and planting roots, and transplanting. Cultivate new patches which you can later harvest from.

- Target your efforts towards at-risk plants. Look for plant populations that are in danger of disappearing (from overharvesting, loss of habitat, etc) and target your efforts to help cultivate them. This may mean that there are certain plant populations that you do not harvest until a more stable population is established.

- Create a balance between foraging and wild-tending: Strive to balance your practices between foraging and wild tending, both in terms of working to cultivate more specific plant populations and also in terms of broader conservation and ecological work, such as protecting wildlands, replanting lands, engaging in political activism, or working with conservation groups.

Build your Knowledge: Understand the plants that you are harvesting–how they grow, how they function ecologically, and the populations of plants in your area.

- Build your knowledge of ecology and plants. Recognize that there is a lot to know about plants and that this is a lifetime of study. The more you know, the more you are able to apply to your foraging and wildtending practice. Read books, attend workshops, and learn about how your plants function in the ecosystem: where do they grow? how do they grow? What insects/animals depend on them? Which plants can you harvest as much as you want? Start by learning about a few plants and build from there.

- Observe and interact. Don’t depend on the wisdom only in books but get out into your local landscape, observe, and interact. Recognize that the populations in your local area of plants and mushrooms may be radically different than what you read about. Understand what is happening in the areas that you spend time in specifically so you can be more mindful of your interaction.

- Connect, learn, and share with community. We can do more as a community than as individuals, so find ways to connect with like-minded others, building and sharing knowledge. The more we spread these principles and ethical foraging approaches, the more good we can do in the world.

Background on these Principles

I started teaching wild food foraging almost a decade ago after a lifetime of cultivating an ethical practice of foraging and working to regenerate damaged landscapes. I began teaching foraging with the naive and simple premise that if people understood that nature had value for nature, they would honor and respect it, work to protect it, and cultivate a relationship with it. However, this is not the case. But with increasing frequency, as new people get into wild food foraging, I’m seeing something very different emerging: communities of people who see wild food foraging as a treasure hunt, going into areas without any knowledge of the plant populations or sustainable harvesting techniques, and pillaging the ecosystem. And in these same communities, there is strong resistance to any discussion of limits, ethics of foraging, or cultivating reciprocation with the land. But, this situation offers us a chance to grow and to learn how to be better stewards of the land. With that said: what an opportunity for change. We are always learning and expanding our understanding, foraging is an opportunity for this. Be open to changing your perspective and be forgiving and understanding of yourself and others on this foraging path.

Unfortunately, in the wild food community, we see the same colonizing and capitalist attitudes that pervade other aspects of Western society. Here in North America, one of the underlying issues is that nature is treated by most people in the 21st century no different than it was treated in the 16th-19th centuries: as a resource that you can take as much as you want from. The history of colonization here in North America turned carefully cultivated food forests into deserts and destroyed the way of life and culture of indigenous peoples who lived in harmony with nature. The current practices of land ownership and individualism stress this further–the assumption is that if it’s your land, you can do what you want with it regardless of how it impacts other life living there. Many people born into Western culture are enculturated into this colonizing mindset and may not even be conscious of how much it impacts our assumptions and relationship with nature. This mindset drives a set of behaviors that are literally putting our planet–and all life–at risk. Thus, it becomes increasingly clear to me that at least some behavior surrounding wild food foraging is a new take on the very old problem of colonialism.

I’ll give three examples to illustrate the impetus for the principles I offer. When I was a child in the Allegheny Mountains, Wild Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) was easy to find. My grandfather used to harvest it in small quantities and brew it up for us as a special treat. In the years since, with the increasing demand from China and the rising prices for American Ginseng, in all my time spent in the forests here, I have never found a single wild ginseng plant growing. This means that the medicine of American Ginseng is completely closed to the people of the Appalachians, and it should not be. I have only had the opportunity to interact with wild ginseng that someone (myself or others) has planted. And in cultivating it, I’ve realized how incredibly hard it is to establish and grow. Most people cultivating it have less than a 20% success rate with either seeds or roots. In a second example, when a friend and I were co-teaching a wild food class, we came across a patch of woodland nettles. Some of the students in the class immediately went into the patch of nettles like vultures, taking every last nettle. Not 15 minutes before, we had had a discussion of wild food ethics and sustainable harvesting, but this was quickly forgotten with the excitement of the harvest. That nettle patch has since regrown with some careful tending, thankfully, but it took about four years to get as large and beautiful as it was. In a final example, one wild food foraging online group in my region, a person posted a picture of six 5-gallon buckets full of ramps, including the bulbs. This represented an extremely unsustainable harvest for several reasons, not the least of which being that ramps take 1-2 years to germinate from seed and up to 7 years to mature. When I kindly shared information about how to harvest ramps more sustainably (very limited or no bulb harvests depending on the population, being mindful of the amount being taken, scattering seeds to propagate ramps), I was banned from the group for “pick shaming.” Most online groups have very strong and immediate reactions to anyone discussing ethics, sustainability, or limited harvests, which prevent any conversations from taking place.

These three examples illustrate the challenges present with overharvesting and were part of the impetus for the above principles. I will also note that all of these examples come from the United States; I don’t know if the issues I’ve witnessed apply to other contexts or cultures.

I’ve never met a wild food instructor, teacher of herbalism, or earth skills instructor who didn’t do their best to teach at least some of the principles I’ve outlined above. But it seems that we need to do more, particularly as large numbers of new people are picking up wild food foraging and that many online spaces are opposed to discussions of the ethics of practice. These principles can be a critical part of every class we teach, every social media post, every Youtube video we create, and every publication we author. By adhering to a set of ethical standards that put wild food foraging in the broader context of building a reciprocal relationship with nature, I believe we can create a more balanced and ethical practice for all.

Examples of the Ethics in Action: Working with Milkweed, Garic Mustard, and Oak

Here are three specific examples how this might be done, both from a teaching standpoint and from a practitioner standpoint:

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is one of my favorite wild edible plants, with four different harvests throughout the season. A wild food foraging practice that includes common milkweed has a chance for causing harm. Overharvesting shoots can prevent the plants from growing at all; overharvesting flower buds, immature seedpods, or silks can prevent the milkweed from going to seed and spreading. In most areas in the US, common milkweed is in decline due to new farming techniques, spraying, mowing, and land-use changes. Thus, our land needs a lot more common milkweed, which is a critical food source for declining insect populations, including the increasingly endangered Monarch butterfly.

When I teach common milkweed, I start by passing out small packets of common milkweed seeds that I have grown in my garden from local seed stock. I tell people about what a wonderful wild food that common milkweed is, how good it tastes, and how to prepare it. And, I ask that people work to cultivate their own patch (in their garden, yard, or in a wild area) so that they can eventually start harvesting it themselves. I explain that I do not, ever, harvest this in the wild but rather, I cultivate new patches and eventually return to them to harvest. In this example, I teach Common Milkweed in context: not only what it is but how to harvest, but the challenges surrounding it. And, I put the direct tools for change–seeds–in their hands, so that they can spread them and begin their relationship with milkweed from a place of reciprocation and stewardship.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is another plant I commonly use and teach. The lesson of this Garlic Mustard is a very different one: Garlic mustard is an opportunistic plant (I avoid the term “invasive”, also for ethical reasons) and by harvesting, we can control the populations of this plant. Because it is always abundant and opportunistic, not only do I teach this plant, I encourage those on my plant walks to harvest as much of it as they can while we are on the plant walk. I will sometimes bring a garlic mustard pesto or another dish that they can taste to see how delicious it is. On social media, I will share recipes and information on how to find it and cook it, so that others can also start harvesting this plant abundantly.

Oak (Quercus Rubra, Quercus Spp.) is another one of my favorite trees from a foraging perspective. When I teach oak in the fall, I usually bring a sample of acorn bread or cake so people can get a sense of how delicious the oak is. This helps people recognize and honor the oak tree as such an abundant resource. We discuss the principle of the “mast year” and how you can harvest acorns. We discuss how to identify good acorns to harvest based on examining their caps and shells. We do talk about how much one can reasonably harvest and process–and how to leave acorns for wildlife. I also teach wildtending practices with Oak in two ways: first, I encourage them to be like a squirrel, not only harvesting acorns but, after harvesting, taking a stick and popping some of them back into the ground to propagate the oak. I also encourage people to return to their favorite oak in the spring and dig up some of the small oak seedlings to spread elsewhere, ensuring the genetics of the tree survive. This creates a balanced relationship with the oak, and helps repopulate a keystone species in our bioregion.

In all three examples, I’ve developed both a teaching and foraging practice based on examining the specific context in which a plant or tree grows, its abundance, and the ecological needs it has. In the case of Milkweed, declining amounts of milkweed (including in my immediate ecosystem) have led me to cultivate it in a number of places, spreading those seeds outward, and considerably limiting how much milkweed I enjoy eating. The case with Garlic Mustard is the opposite–I harvest and eat as much of it as I can as a way of limiting the spread. One of the practices of the oak is to participate in acorn planting and spreading oak trees. Each of these wildtending practices allows me not only to ethically balance a foraging practice but to create a deeper and more meaningful relationship with the living earth.

I would love to hear thoughts on these principles and other ideas for how we can cultivate ethics of reciprocation within wild food foraging!

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Thank you for this. I’m off to a backyard ID appointment, but wanted to thank you in this moment and will completely read later. I learned of a ginseng poacher in my town (Dublin, NH) a few days ago, have lost sleep over it, and have come to the conclusion that I just need to teach about exactly what you are talking about here. I’ll figure out how to download your images when I get back and amplify….Coincidentally, I also met someone starting a forest garden in town the very next day. The Universe balanced it out for me, so I can just focus on my sphere of influence — the people who attend my classes.

Anyway, thanks. Lovely, as usual. And such necessary education. We talked about your blog and your new book during the class I taught yesterday. Thank you.

Katherine

>

Hi Katherine,

We have SO many ginseng poachers around here; it is really sad and you pretty much can’t find it anywhere any longer. I’m so sad that this plant doesn’t have the opportunity just to live and thrive here and that medicine is no longer available to people who live on these mountains. It should be!

Please do use the images and share as widely as possible!

This is so very important! Another issue is that even if every forager is responsible, if several come across the same patch, not realizing that 3 foragers have already foraged there (for example), eventually that patch will become depleted. The difference in biodiversity in the woods I grew up in (White Mountains of NH back in the 50s and 60s) when I was a child and now is devastating to me. People bring their consumer mindset with them into the natural world. It’s hard to let go of. In my Fryeburg Maine garden (I moved from there to NY in 2018), I had started and cultivated a patch of goldenseal from 3 roots I got from United Plant Savers (that UPS got from Strictly Medicinal Seeds, that sells beautiful roots, just FYI). From those three roots I had a patch about 4’ x 8’ from roots spreading and I also learned how to germinate the seeds properly and so many plants were started from the seed. Before I moved here, rather than risk the new owners (who wanted the garden but didn’t have much gardening experience), I donated the patch to the town of Fryeburg, and friends came a carefully dug the patch up and replanted it in the town forest. It is still growing there, but not spreading since I believe the birds are eating the berry before it can fall and germinate. Over the years, I shared some of the seeds with friends who planted them, some with success, some not. I need to add here that the goldenseal was in what I called the woodland part of the garden because goldenseal needs shade.

Hi Susan,

Thanks for sharing. I’m so glad to hear about your goldenseal story! That’s so wonderful.

I came up with this after having some hard ethical conversations with myself about whether or not I was going to continue to teach wild food foraging post-pandemic. After all of my classes were cancelled in 2020, and in seeing the just awful behavior in many online groups, I really wasn’t sure. But I decided that if I didn’t do it, others would, and maybe if I created these graphics, etc, others could use them too.

Anyways, we have a lot of work to do, but I think its worth doing. Moving away from consumerism and colonialism starts with each of us and the work we do in the world! Blessings, Dana

Your graphics are wonderful, Dana!

Dana,

Such a beautiful kindred spirit – so resonate with your intention and truth!

Blessings!

Stacy

Thank you, Stacy! 🙂 Blessings to you!

How does one distinguish between Garlic Mustard and Snakeroot? They look so much the same. Danny

[image: image.png] Snakeroot

On Sun, Aug 15, 2021 at 7:33 AM The Druid’s Garden wrote:

> Dana posted: ” Foraging for wild foods, mushrooms, and wild medicines is > something that is growing as a pastime for many people. The joy of foraging > from the land connects us to our ancient and primal roots and allows us a > chance to build a more direct connection with” >

Garlic mustard has scalloped and rounded leaves while white snakeroot is pointed. Also, if you end up accidentally cooking it, snakeroot has a horrible tarry rubber taste which makes it clear quite quickly as to what it is! (Don’t ask me how I know this, haha!)

This is wonderful. What a gift to us teachers! I am going to frame this and hang it in our classroom. Thank you so much for offering this to the community Dana.

Hi Cheryl,

Thank you so much! I’m so glad this is useful to you 🙂

[…] Principles of Ethical Foraging […]

Dear Dana,

As soon as I read “western Pennsylvania” you had my attention. My immigrant ancestors settled in Mahoning County, OH in the early 1900’s. Your article moves me in so many ways and I now have new avenues to explore in my journey with earth pigments. I am not new to a love for soils, but realize how little I know. Hoping to continue learning, I bow to your efforts. Thank you.

Hi Roxanne, glad you are here and exploring the world of earth pigments! I feel like we all have so much learning, connecting, and remembering to do. Blessings to you! 🙂

A very interesting article… I really enjoyed reading it…!

🇯🇲🏖️