I think it is easy to forget in this day and age that so many of our traditional art forms are directly rooted in the living earth, and reconnecting with those ancient forms can bring us closer to nature. This allows us to be more deeply connected with nature outside of our door and learn how to source more of our basic needs–including supplies for our art and craft purposes–from nature. These practices connect us, inspire us, fill us with joy, and teach us powerful lessons in resilience, balance, and reciprocation. One of my own ongoing committments as an artist is to continually look to nature to help support my journey.

One of the most inspiring things about my visit to the John C. Campbell Folk School last month was getting to see their dye garden. While I was not taking a class that was using dye plants, I was extremely impressed by the number of dye plants they were growing and their dedication to preserving this beautiful craft form. Today, I wanted to talk about dye plants and offer a tour of this delightful garden. In doing so, I’ll introduce some of the best dye plants and share some of their uses and preparation.

The Colors of the Land and Traditional Dye Plants

Before the development of synthetic dye, many traditional cultures’ art, clothing, fine crafts, pottery, and other cultural objects were often defined by the local colors available in their landscape. Often, the other colors that they could trade and get from faraway places were reserved for very special clothing, events, or purposes. These traditional dyes included those found or produced by plants (walnut, indigo, woad madder, turmeric, buckthorn), those produced by various means(lamp black, etc), those found in animals or animal products (bone black, cochineal, carmine), and those found in minerals (red ochre, iron oxide, copper, ultramarine, cobalt). Many of these ancient dyes have been with us for thousands, and in some cases, tens of thousands of years, meaning that these dye plants in particular have very longstanding relationships with humanity (and that makes for some interesting plant spirit work!)

These beautiful dyes have rich cultural traditions that led to unique art forms. For example, the Siberian Ice Maiden Princess Ukok has incredible tattoos that were likely created from black from charcoal. One of the oldest pigments we have records of is red ochre, which is found in cave paintings globally and to this day, is beloved of those making natural watercolors and exploring and foraging for earth-based pigments. Even in traditional art forms like Pysanky, the style is tied to the colors available in Europe when this art form was being created: the traditional palate is black, white, red, orange, and yellow–which were natural dyes that were readily available in Slavic countries for centuries and that could be made at home (and once you read through this list, you’ll see why!). From these traditional dyes, entire traditions of art, craft, and fine craft were born. By rekindling a relationship with these traditional dyes, we can better connect to our ancestors of craft and the natural world that produces them.

Today, many artists and craftspeople are reconnecting to their local landscapes by exploring dyes, pigments, and ochres and what they offer, and through this, finding their way back into more traditional methods of adding color to any number of projects. I’ve been interested in these natural art forms for a long time, through my recently released TreeLore Oracle (which was an eco-printed project), and as documented in various blog posts such as foraging for earth-based pigments, making homemade berry inks, and acorn ink.

What I have loved about my own long-term exploration into natural dyes and pigments is that you can apply them to so many different art forms: on fabric and yarn, on leather, as a wood stain, on pottery, in traditional paint media (watercolor, oil, gouache, egg tempera), on eggs/pysanka, on paper, and even in natural building. And today, with seeds easy to acquire and a renewed interest in natural dyes and pigments, there are many opportunities to learn and grow. In my own bardic practice, most of my experience using dye plants is through creating watercolor paint, natural inks, working with indigo and other natural dyes for clothing, and doing eco-printing on leather and paper. I’m excited to expand my use of dyes to dye much more of my own clothing, integrate into pysanky, deepen my leatherwork through dye, and maybe some other art areas as I learn more about what pigments I can grow and forage.

A Walk Through a Dyer’s Garden

When I was at John C. Campbell, one afternoon we were able to tour their extensive gardens. One of the newest gardens they had was a dye garden, a garden that they had just dedicated some weeks before we came. It was filled with so many different dye plants, plants that were dried and then used in their various classes in eco-printing, natural dye, fiber arts, and more. This garden is not only a great resource for the classes but offers a wonderful teaching tool and introduction to many dye plants that can be grown in temperate climates. We were given a wonderful tour that shared about the work they do in the garden, how they harvest and prepare the plants and the cultivation of these various historical sources of color.

As a fun aside, you can learn a little more about Latin plant names from this list–many of the most major historical dye plants are called “tinctoria” (in the same way you often would see “officinalis” for herbal plants or “wort” listed in common names for healing).

This photo is the opening and signage to the garden, which features signage, some cool wooden art, and also a pollinator hedge. The emphasis on the pollinator hedge here is an important feature–with the massive decline in insect populations, the more we can support pollinators through gardening practices, the better. Thus, I always recommend growing a pollinator hedge!

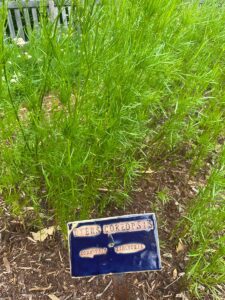

Woad (Isatis Tinctoria)

Our first plant is Woad. Woad (Isatis tinctoria) creates a beautiful blue dye shifting towards the green spectrum. Woad is well known as a dye for those interested in Celtic mythology and druidry because this was a dye that was used extensively by the Ancient Celts. In fact, Woad, which is native to Turkey, has been used throughout the Middle East and Europe since Neolithic times, meaning that humans have had a very long relationship with this plant. Woad was used to dye fabric that Egyptians wrapped mummies in, and most famously, Julius Caesar noted that the Celts tattooed and painted themselves in woad before going into battle. Woad was one of three primary dyes used throughout Europe along with Weld (yellow) and Madder (red), both of which are discussed below. Woad fell out of favor for the bolder and easier-to-use Indigo blue in the 18th century, but Woad is still a fabulous dye plant!

Weld (Reseda Luteola)

Our second plant in the trinity of Middle Ages dye plants is Weld (Ruseda Luteola). Weld is a plant that produces a beautiful bright yellow dye and was used consistently until the 19th century when synthetic aniline dyes came into production (which were cheaper and easier to produce). This beautiful yellow could be over-died with Woad to produce a green (often called Lincoln green). Weld prefers to grow on sandy, dry soil rather than rich, moist soil (so if you are planting her, keep this in mind). Like some other dye plants, Weld is best harvested before the fruit forms or you will not get as much dye. Weld was in use by at least 10,000 B.C., which is likely earlier than either Woad or Madder. In ancient Rome, Weld was used almost exclusively to dye wedding garments of virgins a beautiful yellow. In other parts of the world, Weld yellow dye was used much more widely in Europe after the fall of Rome. Weld produces one of the most pure yellow pigments of any plant on earth. I will also note that as you see in this list, many other plants can produce a nice yellow dye, but none do so as well as Weld.

Madder (Rubia Tinctorium, Rubia Peregrina, Rubia Cordifolia)

Our third of the trinity of Medieval dyes is Madder, which humans have used as a dye plant for at least 5,000 years. The Madder root produces Rose Madder dye, which is a beautiful red dye specifically created from the roots of older plants. Thse roots should be at least three years old but ideally five years old. Several plants are called “Madder” and produce the red dye; what is pictured here is Rubia Tinctorum. Madder was an important dye plant grown throughout Asia, the Middle East, and Europe and has been used to dye the cloaks of women in Lybia, the wrappings of Egyptian mummies, and also used in portrait paintings throughout Europe. Archeologists even found Madder in linen in Tutankhamun’s tomb from 1350 BC and also in the wool found in ancient Norse burial sites. Madder was also used to dye leather; a 4000BC Egyptian quiver for arrows had traces of Madder. Growing Madder requires patience, the roots of the plants cannot be harvested for dye for at least three years, but ideally, five years. Thus, if you want to grow madder, you want multiple plots so you can have a rotational planting and digging cycle. I’ve just made that long-term commitment to growing Madder, so I’ll check back in five years and let you know how it goes!

Indigo (Indigofera Tinctoria, Persicaria Tinctoria)

No dye garden could be complete without Indigo. Some Indigo, such as Indigo Tinctoria, come from the Indigo family of plants, many of which produce dye, but many of which are grown in very hot climates around the equator in places like India. Thus, they are less accessible to people in more temperate climates.

For those of us growing in temperate climates, Japanese Indigo (Persicaria tinctoria) (which is featured here) represents a wonderful alternative option–this plant can be grown as a tender annual, and the leaves are harvested before the plant goes into flower, often in several harvests. Once the plant produced flowers, the flowers lessen the quality of the dye–this makes sense because the energy of the plant moves into flower/seed production. You can harvest the leaves at any branching point throughout the season and dry leaves for later use.

Indigo has been in use by humans for dye for at least 6000 years, with a rich tradition originating in South-East Asia and Mesoamerica and spreading through the world. A Babylonian cuneiform tablet (stone tablet) shares the recipe for how to dye wool cloth with Indigo. Indigo was used by many ancient civilizations such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, West Africa, Iran, Peru, Egypt, and India. Because Indigo Tinctoria cannot be grown in temperate climates, in Europe, Indigo was considered a luxury item (and until the more modern era, Woad was the traditional blue dye). The Romans used Indigo primarily for pigment painting, garments, and cosmetics–but Indigo was always imported to Rome and Greece, making the plant dye quite expensive. Everyone knows the color of Indigo, as that is the color of blue denim jeans. Indigo dyeing as a fine craft has been also experiencing a resurgence of interest globally, and it is a very easy and accessible plant dye to work with.

This changed when a new sea-based trade route was discovered in the late 15th century, which made it easier to import Indigo by sea rather than by land routes.

Here’s where things get troublesome. As Woad–which anyone could grow and use–declined in Europe and Indigo grew into favor as the blue dye, colonialization, and industrialization reared their ugly heads. This always seems the case–mass production and demand, when taken out of the hands of everyday people, allow for exploitation. Unfortunately, Indigo became one of the larger crops that were grown and processed using slave labor from Central and South America to address the demand in the old world. Enslaved Black and Indigenous peoples were forced to work these Indigo plantations under terrible conditions due to the high demand for Indigo in Europe.

While Indigo is no longer produced in this fashion, this history is a good reminder of why it is critical with any naturally-derived things to ensure either you are growing and/or ethically harvesting yourself or ensuring you are getting your plant matter from ethical, regenerative sources. Bringing ourselves back into healthy balance with the plant kingdom by working to grow our own allows us to know every step of the process. To process indigo from leaves is fairly complex, involved process that is described here. I’m using these leaves fresh or dried for ecoprinting, meaning that I can use them right from the plant.

I have been experimenting with using indigo leaves in my ecoprints, including new experiments on paper, leather, and fabric!

Dyer’s Chamomile (Cota Tinctoria)

As far as I can tell, Dyer’s Chamomile does not have the rich history of the earlier plants on the list above but is still a very good dye plant that is used to produce yellow, gold, buff, and golden-orange dyes primarily for fabric. The flowers produce the dye–you can use them fresh or harvest and store them for later use for dying wool and fabric with beautiful golden and orange hues. Most of the sources I read suggest this plant may be biennial or perennial in certain climates, but most dyers will start new seeds each year to ensure a good harvest. Using the flowers in ecoprinting and leather ecoprinting has yielded rich yellows as one would expect.

Dyers Chamomile, being in the Chamomile family, also is a great medicinal plant for insect stings and functions as an antispasmodic, emetic, vesicant, and diaphoretic in tea, tincture, or fresh compress form. Thus, there are many reasons to include Dyer’s Chamomile in the garden!

Holly Hock (Alcea Rosea)

Hollyhocks are perennial flowering plant that has flowers used for dye. Holly Hock with black flowers produces lavender and purple shades; if you change the PH of the dye bath (by adding iron, vinegar, etc), you may also be able to obtain blues and greens. The blossoms are gathered from mid to late summer and either used fresh or dried for later use. Fresh is typically a 2:1 ratio of blossom weight to fiber, while dried use a 1:10 ratio of blossom weight to fiber and an alum mordant. These delightful plants also can grow up to 6-8 feet tall (we currently have a Hollyhock in our garden that is well above our heads and blooming beautifully!)

Coriopsis (Coriposis Tinctoria)

Coriopsis is another delightful plant found in many dye gardens. This is a North American plant that is annual in nature that is quite easy to grow and regularly self-seeds. Coriposis prefers to grow in full sun and, once they are flowering, each plant produces hundreds of flowers which are used for dye. Coriposis yields a range of orange to brown dyes, particularly on wool and silk (Coriposis is not as great for dying cotton or other vegetable fibers; I haven’t tried the dye on leather yet!)

Yarrow (Achillea Millefolium)

Yarrow is an incredible herb with a wide range of medicinal uses, including my favorite–stopping blood from flowing from open wounds (which is how she earned the name “woundwort.” But beyond her medicinal action, Yarrow is also an excellent dye plant. In eco-printing, she prints a beautiful yellow-gold, and on fabrics and yarn, Yarrow offers a range of choices: yellow and with the addition of iron as a mordant, you can also get olive green shades. The flowering tops of the plant are what are used to create dye; you can keep harvesting them if you cut them at least 6″ from the soil, so the Yarrow can grow back again. She is a perennial plant and is quite drought-tolerant.

Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

Most people who use Tansy gather her wild because she is often considered invasive and is therefore easy to find. But she’s not really wild in all parts of the world, so some people cultivate her in the dye garden. Her lovely button-like yellow flowers produce a beautiful golden-yellow dye. While there are a lot of plants (including many on this list) that produce a yellow dye, she has a very high-quality dye that has lasting effects, with similar chemical constituents to Weld, including offering a higher lightfastness in her dye. She also can produce bronzes, greens, and beautiful greens with Iron (ferrous sulfate) (shifting to bronze/earthy green) or alkaline treatment with vinegar or baking soda (orange). She also works well with Indigo, so you can get lovely greens with an overdye, dying the tansy and then later dying Indigo. I like to use a rust garden with Tansy, which can be created by putting iron objects in vinegar and keeping them stored in something all plastic–I’ve had a rust garden going since 2019 and it is great for using for ecoprinting and natural dye.

I will also mention that Tansy is another plant that has a history of traditional medicinal uses (including being an abortifacient and dealing with internal parasites). However, she is typically not used medicinally as much these days because she also has alpha-thujone, which is toxic.

Iris / Bearded Iris (Iris Germanica)

Conclusion

Given this abundance of plants, some of which I already grow, I was excited to expand my dye opportunities and learn some new plants to grow. Lucky for me, I didn’t have to wait till next year: John C. Campbell had plant starts available both of the Madder and Japanese Indigo and thus, I was able to lovingly prepare space for them and plant them at the Druid’s Garden homestead. I’ve already begun experimenting with leaves for dye from the Indigo. The Indigo will be harvested this year, and I’ll cultivate a long relationship with the Madder and maybe in about 4-5 years, you’ll hear about how it went. In the meantime I will continue to enjoy and work with many of these other plants that we already grow–Holly Hock, Chamomile, and Yarrow–and hopefully add some new ones in the next growing season.

Announcements

To wrap up this post, I’d also like to share some announcements:

1. I’m delighted to share that I have a release date for my next book, Land Healing: Physical, Metaphysical, and Ritual Approaches to Healing the Earth. This book, released by REDFeather is coming out next year on March 28th, 2024. If you don’t want to miss any announcements about this book or my other works, subscribe to this blog via WordPress or join my infrequent newsletter.

2. I have started a TikTok channel that offers short videos of what is happening around the homestead on a hopefully regular basis. This is going to be more informal and in the moment than my more polished stuff here. Feel free to check it out if you are on TikTok! And if you haven’t checked out my Instagram (which is primarily where I share my art, you are welcome to check that out too).

3. This blog was recently quoted on Vox in an article about AI Divination. I’m thankful that the reporter was willing to share my perspective on the use of AI in human spiritual tools, which I share here. I’m glad that we are raising awareness about the problems of AI-generated images, particularly in spiritual contexts.

4: Finally, I want to share that my current book writing project is on the bardic arts and sacred creativity, so you’ll probably be getting a lot of bardic and creativity-themed posts from me in the next year or so. I hope to wrap up writing this book by the end of the year, depending on how things go :).

Enjoyed you article so much, I had a small Dyers garden a few years ago before I moved into my current house, a few days before my move I had dug all the plants I wanted to take with me put them in pots to take to the new house. The day of the move I went back to the house to do a last minute check and to load the plants into my car to take home. When I arrived all the plants were gone this was nearly as heartbreaking as when I went on vacation only to come back to my healing garden completely dug up and well trampled. Injury and recover has prevented me from gardening but slow healing has me hopeful this Fall I am optimistic and plan to prepare my garden beds for a garden.

Ohhh..I’m so sad to hear about your experiences with your garden. I hope eventually you will be able to start something in the Fall! Maybe this post offers some inspiration!