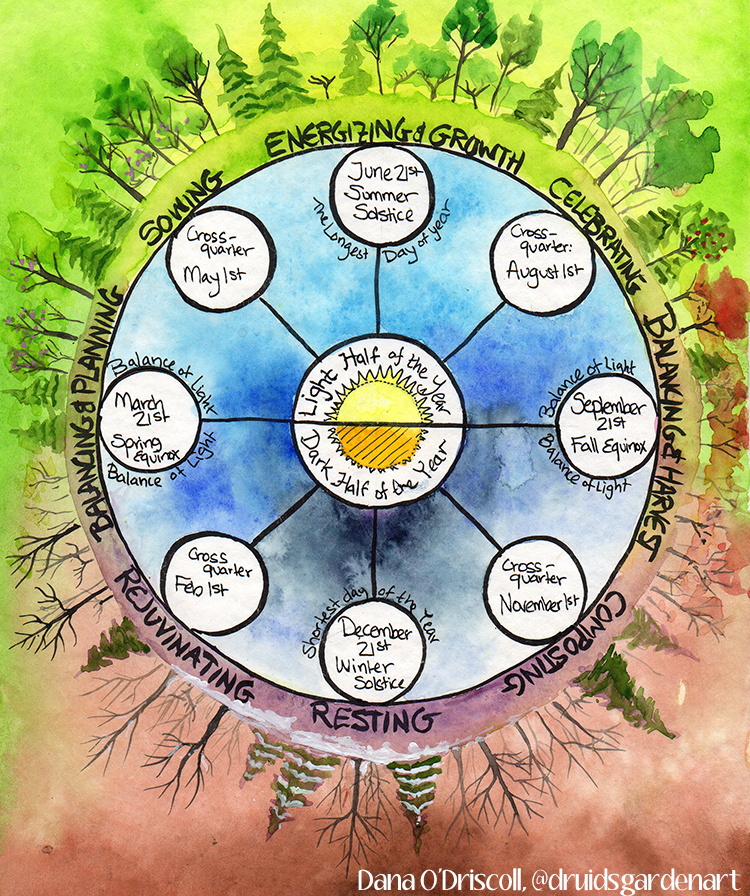

The Wheel of the Year is obviously a powerful symbol, both in nature spiritual practices like druidry as well as more general neopagan practices. It resonates with something that is ancestral and connected–living by the cycles and honoring the seasons. A host of different traditions use some form of a yearly wheel, and when you join many traditions, the wheel of the year is a critical part of the practice. But what do these holidays mean? How do they actually connect to our lives? How do they connect to our local ecosystems, and how do the wheel holidays help us connect with nature? I consider these questions and argue for a wildcrafted wheel of the year rooted in your own observation, connection, and daily life in connection with nature.

As a druid for the last 16 years, I feel like this is a question I continue to return to over and over again. I even wrote a book on sustainable living practices as sacred action using a wheel of the year framework (see Sacred Actions) trying to explore these issues from yet another perspective. I’ve celebrated these in all sorts of ways–by myself and in various groves and groups, formally and less formally, with other people’s rituals and my own. And yet, I feel like almost every year, I get another piece of what it means to really live this wheel but also what complications and changes I have to make.

When I first took up the path of druidry when I was still in college, I began celebrating the wheel by looking at rituals in books and enacting them. There was nothing wrong with this approach, but I was essentially bringing in other people’s visions and classical interpretations of the wheel from an ecosystem in which I didn’t live. It was a good foundation and gave me a connection to a tradition I was still attempting to understand. However, it wasn’t until I really started delving deeply into wildcrafting my own druidry and developing an eco-regional approach that I really started to understand these practices.

I had an epiphany this week about Imbolc and the real power of this holiday. We had a pretty warm December and then January plunged us into very cold and dark times. January was exhausting after weeks of sub-zero temperatures where we were trying to keep our animals warm, bringing hot buckets of water out to them several times a day, learning how to live with chickens in a tent in our spare bedroom–the chickens can’t handle the bitter cold we had. Thus, the handsome Pythagoras, our roo, woke us up crowing up the sun every day! Each morning, I’d face the bitter cold to tend to the animals, coming in like an icicle to warm by the fire (which I had to stoke and tend before venturing out). We spent our days making sure we had enough wood, and one of us was always up tending the fires throughout the night and wee morning hours. It was pretty intense. This was deep winter, cold winter, dark winter, where the sun hardly even came out of the sky. And then, on January 31st, the weather broke. We moved out of the teens and had a 30-degree day (I’m speaking Fahrenheit here!). The chickens got to leave their house tent purgatory, and the ducks and geese had their pools filled with water for the first time in weeks. As the geese and ducks joyfully swam in their pool, you could see the joy and relief on their faces. They knew the weather had shifted. And then February 1st came and with it the flowing of the maple trees. The wheel had just turned from dark winter into late winter, and we celebrated Imbolc and tapped our maple trees.

I tell this story because, if I hadn’t lived on a homestead where we are required to go outside many times a day to tend our animals, the importance of this day would have likely been lost. I remember when I lived in an apartment, dorms, or a townhouse–I didn’t really pay attention much. I would have probably turned up the heat, ran the water a little extra to prevent the pipes from freezing, and then thought nothing of it on the way to the car or into a building. Because that’s how it is in modern life is–everything is designed to make you a cog in the machine that never changes. Regardless of what is happening in the ecosystem, you just keep on going. But that’s not really what creates a deeply connected and wildcrafted wheel of the year. Crafting our own wheel requires us to pay attention.

It was the experience of having to be out there in the cold for weeks on end, seeing the animals enduring the cold and suffering, and then after all of that, experiencing that powerful break in the weather and the first thaw. As soon as the thaw happened, local wildlife changed activities, our flocks grew much more active and happy, our own spirits lifted as the temperatures rose. When I think about the historical origins of Imbolc, how it was a holiday originally surrounding the lactating of ewes, I say yes–this must have been such a relief to those farmers and peasants who had just suffered through a difficult January. Maybe the food stores were running a bit scarce. Maybe they woke up for the 30th day in a row and froze each morning like I did while taking care of the animals and think…will this ever end? And then, suddenly, it does. That was the power of Imbolc. The breaking of the cold and dark times. The promise that spring will return. The flow of milk–of nutrients, of life.

I write all of this to illustrate a simple point: these holidays make more sense when we are deeply embedded in our landscape. When we are deeply connected with nature, when we are out in it every day, when we–through our own life choices or commitments–are required to endure it along with the rest of nature, then we can learn the lessons the wheel really offers us. Living the wheel of the year–not just celebrating it–teaches us the important lessons of that moment. When we spend time in nature and commit to being out there, then we are forced to contend with whatever nature throws at us. When we are understanding the holidays not only in terms of history or lore but based on our actual experience, then the wheel of the year unfolds for us.

And this is critical–in order to make the wheel of the year yours, a wildcrafted wheel that you build yourself, one of the best approaches is to find seasonal markers that make sense for you (I shared a lot more about this approach earlier in this post). Maybe it’s the flow of the maples or the return of the robin, maybe it’s the hawthorn blossoming. To me, these moments in our own landscapes are much more important than dates we may have from traditions that are far removed from us. These kinds of key observational markers also will make sense in the age of the Anthropocene, when climate change is throwing off traditional seasons.

And here’s the other thing I learned through this process–not everyone has an eightfold wheel of the year. Your wheel might be threefold, binary (rainy and dry), or even more. In fact, I worked up a 12-fold wheel of the year for my region that actually works better than the eight (I shared that philosophy on the link above). The idea being that there are distinct phases of each of the four seasons (and 4×3 = 12). My 12-fold wheel allows me to understand my ecosystem in much more detail and allows me to see each season as waxing and waning. What I found in creating these wildcrafted seasonal markers is that I start to anticipate them, look forward to them, and honor them as they occur. So rather than having arbitrary dates and times that are disconnected, I do what my ancient ancestors did–I observe, make meaning of the observations, and build that into my spiritual practice. And, I learn to honor and appreciate holidays like Imbolc at a deeper level.

What I’m suggesting takes time and effort. You don’t have to do it all at once. I suggest taking some time, a year and a day, maybe even longer, and simply observing what is right outside your door. Ideally, your seasonal markers for the wheel will be happening in your everyday life–and if you are in an urban setting, they may also be dictated by the patterns of people as well as nature. E.g. perhaps the early part of summer is when the local public pool opens. The built and human-based environment is still part of our environment; we are all part of nature.

PS: This is part of my Ancient Order of Druids in America-themed posts. AODA as a druid order is extremely committed to helping druids “wildcraft” their druidries and create local practices. I am currently the Grand Archdruid in AODA, and have been a member for the last 16 years. For more information on AODA, please visit www.aoda.org.

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Thanks for the reblog!

I really enjoyed this. Thank you!!

Truly awe inspiring. As a Druid who is always just beginning to go deeper into practice with the intension to meld further with Nature—to not be separate but unified—this post and all others are a great and continuing resource. Pithy content and excellent writing. I want to apprentice!

Hi Steve, thanks for reading and for your comment! Glad you found the post useful!

Reblogged this on Rattiesforeverworldpresscom.

How wonderfulx

[…] Nature Connection, Wildcrafting, and the Wheel of the Year […]

I really appreciate this post about being grounded in one’s own environment as foundational for our sacred practices and

journey. In some interesting ways your post parallels the book I am currently reading by Doug Tallamy – Bringing Nature Home.

And just when we hear the maple sap start moving, Winter reminds us she’s not ready to let go. Or so it seems here in southwestern PA. But the longer days and St Brigid Day celebrations remind us we have crossed the line. The sap will run soon. Patience!

Haha, she’s never ready to let go, not with the Groundhog saying otherwise! But right now, I’m heading outside to empty my sap buckets…it is 40 degrees and I am grateful :).

Hello Dana..

Linnie (A’HA Oracle( here again 🥰

My last reply to your online enquiry was pribably confusing. If you’re happy to email me your postal address I’ll just send you adeck, as a gift, because I enjoy your blog and your sharing re Druidry so I’d like to make a gift of it .. if that feels ok to you I’ll wrap a deck for you and next time I’m in ‘big’ town I’ll post it 🥰🙏

Many blessings to you

(((((((hug)))))))

Linnie Lambrechtsen

Reflecting on your post I have realised I am often scared by changes in nature, particularly at this time of the year, because of climate change. Winters in my part of the UK have become unseasonably mild. Tiny cherry trees start blossoming in January and I worry for them. I pointed out the first snowdrops to my girls today and found myself immediately thinking is this the ‘right’ time for them? Is it the same as last year? Or when I was a child? So although I do the first aspect- trying to live in my environment in the moment, and observe it with fascination and joy, as soon as I start mapping my observations to the wheel I become tense. I know nature is adaptive and this is ‘good’ but hate that we are driving this change. I also feel it is important to keep looking at the shadow side of humanity, that nature is directing me to do so.

In summary, I totally agree with what you are suggesting we do. I wanted to share why I find it hard, to encourage myself and others not to let this be a barrier.

Hi Nicola, thanks so much for your comment. I’m pretty scared by what is happening too. I’ve been wanting to write about it, but I’m not even sure what to say. I’m working on it, for myself, and maybe someday, I will have something to share. The one thing I can say now is that I do think it’s important to keep looking, to acknowledge, to hold space, and to witness. It is terrifying work, but still work we must do. Thank you so much for this perspective.