I remember when I first spotted to Wild Grape patch from the dirt road. “Is that all wild grape?” I said to my friend in an excited voice. We pulled the car over, and sure enough, there were thousands of grape bunches on a patch of vines that stretched hundreds of feet, almost ripe. A week later, we came back to the spot with a larger group of friends–there were more than enough wild grapes to go around. After giving thanks for the abundance and promising to return to the spot for some wassailing in the winter, I harvested almost 5 gallons of wild grape that day. We worked to press all of the wild grapes with a friend’s with a small fruit press, and converting those grapes into the most amazing jelly you ever tasted!

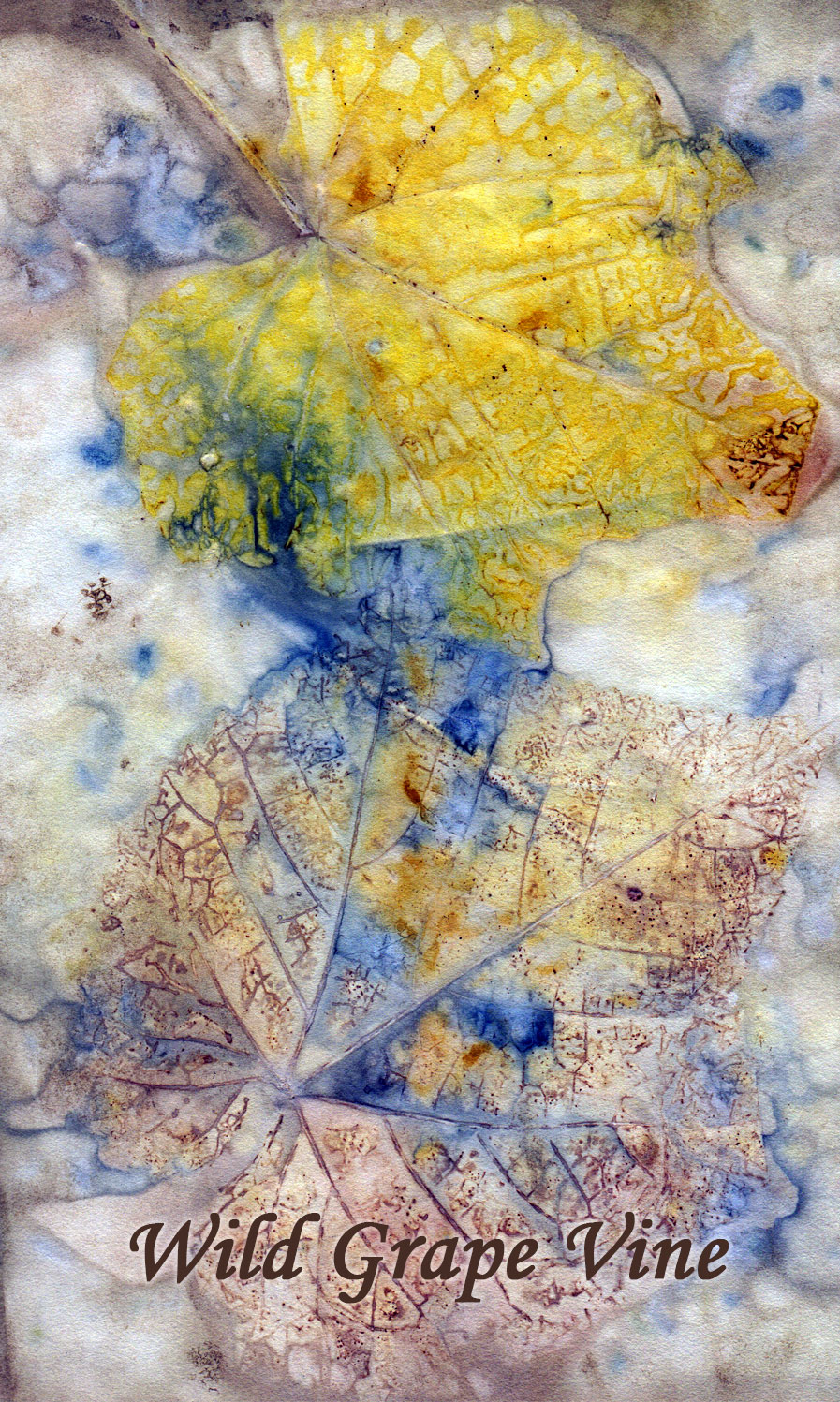

Wild Grapevines, most commonly on the US East Coast the Fox Grape (Vitis Labrusca) variety, are truly a wonderful vine to get to know. They offer a variety of wonderful fruits with medicinal and culinary uses, a whimsical and sacred presence in our forests, and important spiritual lessons to learn. Like apples, pears, and other stonefruits, humans have an extremely longstanding and healthy relationship with grapes. This is, in no small part, the role of wine and other fermented beverages in human history. Before we had modern medicine, the wine was not considered simply an alcoholic beverage but also an important medicine. Grapes, their fruit and leaves, are also an important food source.In today’s post, we will explore the incredible grapevine! While I’m focusing my comments on the most common grapevine along the US east coast, Vitis Labrusca, the fox grape, or wild grape, you can apply the content of this post to all grapevines.

This post is part of my Sacred Trees in the Americas series. In this series, I explore the magic, mythology, herbal, cultural, and divination uses, with the goal of eventually producing a larger work that explores many of our unique trees located on the US East Coast. Other trees in this series include Devils Walking Stick, Witch Hazel, Staghorn Sumac, Chestnut, Cherry, Juniper, Birch, Elder, Walnut, Eastern White Cedar, Hemlock, Sugar Maple, Hawthorn, Hickory, Beech, Ash, White Pine, Black Locust, and Oak. For information on how to work with trees spiritually, you can see my Druid Tree Working series including finding the face of the tree, communicating on the outer planes, communicating on the inner planes, establishing deep connections with trees, working with urban trees, tree energy, seasonal workings, and helping tree spirits pass.

Grapevine Ecology and Growth Habits

Fox Grape is widespread along the US Eastern seaboard, from Nova Scotia to Georgia, and its range stretches through most of the eastern half of North America to the Mississippi. Because of this, it is quite easy to find Fox Grape in foraging adventures, and when found, it is often abundant (although not always easy to reach if it is growing high up in the trees). Fox grape, like other grapevines, is not a freestanding tree. Rather, it depends upon the support of other trees, most often in a symbiotic relationship, where the grapevines are growing with other living trees. However, over time, the vines can strangle the trees, eventually pulling them down. You might see places like this in the forest–it often appears as a U-shaped bowl where thousands of grapevines are growing up the trees–and the center is a mass of grapevines that have pulled down smaller trees and continue growing outward. Several other growth habits I’ve witnessed include wild grape taking over an abandoned pile of wood (imagine a very large brush pile covered in wild grape) or a huge amount of wild grape on the edge of a field/forest, taking up much of the edge space. Most commonly though, you will find a grapevine here or there, often climbing up into the host trees.

The woody vine of the wild grape is usually 10-40′ long with a base of several inches and up to 12″ in diameter for the oldest vines. It uses forked tendrils (also edible) to slowly climb up adjacent trees where it uses its tendrils to anchor itself to branches and continue its ascent. The bark is medium brown and usually appears shredded, with some of it flaking off over time as the vine grows in girth. At regular intervals, the vine will have nodes where stems come out to produce leaves. The leaves are alternate and heart shape with three palmate lobes. In the late spring or early summer, the wild grape will produce greenish-yellow bunches of flowers–they aren’t very showy, and it Is usually easy to miss them. The flowers slowly develop into green grape clusters and then, in the late summer or fall, the 1/2″ – 3/4″ grapes ripen to dark purple or bluish-black. Of course, this is the time to go foraging for wild grapes!

Wild grapes grow in a variety of soils and tolerate a range of conditions, but they prefer wetter conditions and have some flood tolerance. They usually thrive in part sun conditions, and as they climb, they bring themselves into more sunlight, sometimes blocking out the light of their host tree.

Wild Grape History

The Fox grape has an interesting history. It is likely that in the 11th century when Leif Erikson and the Vikings were exploring coastal North America, they named the land they saw as “Vineland” because of the numbers of grapevines present. Fox grapevines along with other Vitis species were later exported to Europe during the 19th century. However, all North American grapevines carry the phylloxera louse that devastated many of the Vitis vinifera (European) varieties of grapes but that the American varieties are immune to. Europeans eventually overcame the phylloxera by interbreeding Fox grape with native European grapes to build resistance. Thus, most of the grapevines in the world have a bit of Fox Grape in them. The Concord grape was also bred from the Fox Grape in the 19th century in Concord, MA and after that other varieties such as the Niagara and Deleware were developed.

Wild Grape as Food

The Fox Grape is a very potent red grape variety, which has a skin that can be easily slipped off, offering easy access to the grape flesh and 4-5 small seeds in the center. According to Winker, Cook, Kliere, and Lider from General Viticulture (1974), the fox grape is known as “fox” because it has a strong, musky aroma that is earthy, sweet, and quite unique. These features make it highly sought out as a wild food.

In Native American Food Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary, Daniel Moerman describes the widespread uses of wild grapes by a variety of Native American tribes for food. This included eating the fruit raw, using the fruit to make juice and dumplings, drying the fruit into raisins, and more.

Today, as traditionally, wild grapes are used as a food source in a number of ways. First, the small forked tendrils coming out of the vines are good for a trailside nibble–they are tart and fresh tasting (you could never gather many of these without harming the vine, so enjoy a few as you hike but don’t consider this a major food source!)

The leaves are a culinary delight: they can be steamed or marinated in oil and then used to make dolmas, casseroles, or other dishes calling for grape leaves. You can preserve them in oil or even parboil and freeze them if you want a ready supply of grape leaves into the winter months.

Of course, the prime food source from the grape is the fruit itself. In the late summer or early fall, keep an eye out for wild grapes that are ripe. Confirm that they are wild grapes (both poison ivy and Virginia creeper can produce a look-alike, identify the difference between the leaves and the size of the fruit). Usually, wild grapes stay on the vine a number of weeks if the wildlife doesn’t get to them first, giving you a long harvest window. As Sam Thayer in the Foragers Harvest notes–and this is important–when you are harvesting, you either need to process your grapes right away or ensure that you do not crush them. The grapes will immediately begin to ferment if crushed (as grapes do!). When you crush them, crush them gently because the seeds can be bitter and that bitterness can be transferred into the grape juice if the seeds are crushed. Thayer notes that a small fruit press or jelly bag is good for this work–I’ve also found you can step on them in a clean bucket with clean feet! Return any seeds or unwanted materials to the living earth.

One of the most important things to know about harvesting wild grapes, at least the Fox Grape variety, is that they contain a compound known as tartrate (a salt/esterate of tartaric acid, found in all grapes but high in wild grape). Different vines have it in larger or smaller amounts, in my experience. After crushing, make sure you wash your hands thoroughly or the Tartrate can start to make your hands burn after about 45 min to 60 min. After you have your juice, put it in the fridge or a cool porch for 24 hours in a large jar. You will see a gray-brown sludge form at the bottom (usually about 1/4 to 1/3 of the total volume).. Pour off everything that isn’t the sludge and discard the sludge in your compost or outside (it is important to return any “waste” to nature. If you don’t pour off the Tartrate, it will provide an “off” taste to your finished juice (or any fermented products you make with it).

What is left is an amazing, very potent, and delicious grape juice. You can mix it with other juices (it goes well with apple or pear), ferment it, make a jelly, drink it fresh, or anything else. At this point, you can use any recipes you want for those calling for Concord or Niagra grapes. My favorite thing to do with it, since I don’t drink alcohol at all, is to turn it into the most incredible jelly you will ever taste! A fruit leather (fruit roll-up) is another excellent use, especially when combined with another fruit like ripe pureed apple.

Wild Grape as Medicine

It’s important to remember that before modern medicine, wine (particularly red wine) was considered as much a medicinal substance as it was a culinary one. Due to the reservitol, which supports healthy heart function, wine has long been used as a medicinal drink and health tonic in many cultures. As Matthew Wood describes in his Earthwise Herbal: Old World Herbs, herbs were often macerated (soaked) in wine, and then it was diluted with honey and water for medicinal use. As Wood notes, in the late Middle Ages, distillation techniques invented which allowed wine to be turned into spirits, creating an even more potent medium for tincturing herbs. Wood notes several other historical uses of grapes including liquid drops from living grapevines being used on the eyes to help heal eye issues and the grape leaves (which are astringent) were used to address a variety of wet or damp stomach conditions.

Wild Grape in the Western Magical Tradition: Europe and the Americas

Vine or Muin is associated most commonly with grapevine, although grapevines are not native to Ireland, where the ogham associated. Still, many contemporary uses of Muin tie it to the wild grapevine (I use it in the Allegheny Mountain Ogham as well). In Celtic Tree Mysteries, Steve Blamires notes that the word Muin is tied to the “highest beauty and strongest effort” in the ancient texts, suggesting that vine grows from tree to tree, connecting the forest, which offers one key interpretation of vine through the ogham (p. 147).

In the American Hoodoo tradition as described by Cat Yronwoode in Hoodoo Root and Herb Magic, the grape is used for revealing adultery revealing spells and also for a very specific kind of curse lifting. If a man has difficulty urinating due to a curse, a rootworker cuts a grapevine to the height of his crotch and then bends it in a glass jar and lets it sit overnight. This will produce a liquid. He should wash his privates with this liquid, which will cure him of the curse.

In The Encyclopedia of Natural Magic, John Michael Greer notes that grapes have been considered magical substances by humans since before we had recorded history. The ancient Greeks called the grapevine the “blood of the earth” representing their critical importance. JMG notes that grapes are tied to the Sun in Pisces and are airy and warm in the 1st degree, moist in the 2nd degree. While grapes were used traditionally in love magic of all kinds, JMG notes that grapes are excellent at carrying the energies of other herbs or substances, which is part of why wine can be the base for many potions, baths, and washes (p. 115).

Wild Grape in Native American Mythology

The Chickasaw Legend describes the Raccoon Clan, a clan of bright and well-adapted people, hanging large bunches of wild grapes up to dry for the winter months. In the History and Traditional Lands of the Huron-Iroquois Nations, the tale describes a large bridge constructed by the Iroquois over the Ohio river which broke after several explorers attempted to cross it. In a similar Senaca legend, the Lazy Man makes a grapevine swing and hangs out in his swing all day rather than doing anything productive like hunting. In The Origin of the Iroquois Nation, the spirits of the sky came down and gave each of the five Iroquois nations a gift. To the Onondaga were given grapes, squashes, and tobacco. In a final Senaca legend, the Adventures of Yellowbird, at one point Yellowbird, who is a shapeshifter, is summoned by a neighboring chief. In animal form, he runs to meet her but is stopped repeatedly by an invisible tangle of grapevines. He knows these vines were put in his way by the chief.

The Magical and Divination Meanings of Wild Grape

Binding and Holding Fast. The first meaning of the wild grape is due to the very nature of grapevine–as vines grow, they grow around other trees and plants, in some cases, strangling them and pulling them down over time. even the small tendrils can cause great difficulty to living plants. This meaning is clear, both in the ecology of the plant as well as in some of the legends surrounding the plant.

Transmission of energy. Just as the grapevines connect multiple trees and the wine can be used to transmit the qualities of herbs, the grapevine as a whole offers a transmission of energy and is a worthy vessel for any sacred sacrament – herbs, magic, and more. Wine is a carrier, it can help carry sacred energies of ritual and more. You might consider how vine can be used as such a transmission source in your own practice–through the wood, through the leaves, or through food and drink that you create.

Dear readers, what are some of your experiences with the wild grape? I would love to hear your insights and thoughts!

Hello,

I am new to your post. I would like to do a research paper on the Wisdom of trees and their significance in the Celtic Traditions. I am a student in David Winston’s Herbal school and I have personal interests in Druides Herbal medicine. I would be grateful for some guidance as there is not much on the ancient Celtic traditions, maybe because it was lost along the way. But I would like to make it revive again, as I know my ancestors are from the Celtic lands and it means a lot to my heart,

Thank you,

Anne Selseotes

>

Hi Anne! If you want to look at Celtic traditions, you should consider exploring Ogham. I would suggest Laurie O’Brien’s Ogham book as a great place to start :). There’s a lot more out there than you might think.

Reblogged this on Blue Dragon Journal.

Thank you so much for this gorgeous, information packed article! As an herbalist, a Witch, and a budding ethnobotanist (😉), your article could not have been more perfect & timely for me!

Yesterday, I stumbled upon a massive stand of wild grapes in a remote area of the woods near my home. I sank to the ground crying upon seeing them, because I hadn’t found any since the crossing of my dear Gran 9 years ago.

She & I had spent many a beautiful day foraging grapes & making juice soaked herbal cordials (as she called them) & jams. We’d gather & preserve the leaves as well because she told me that they carried the energy of summer that our bodies needed in the dark winter days. Later, we’d return for vines & craft wreaths and rustic baskets from them “to remind us of the plant that had given us so much”.

Although she never called herself a Witch or a Druid, she was most certainly a Cunning woman, a Wortcutter, and a Wisewoman! Although she wouldn’t have known or claimed those titles either, she always spoke to anything we gathered, thanking them for their gifts that would sustain us & heal our bodies.

When I forage or cultivate, I still follow her ways, but I leave a traditional offering. Gran, not knowing it was perhaps the greatest offering of all, simply kissed a great leaf and bid the plant farewell until they met again.

She was truly my 1st teacher of herbalism and animism! Gran was more than just the humble country girl with a 6th grade education that she thought she was. She never had time to read or study, but I believe she carried in her heart the memories and ancient knowledge of her Celtic ancestors. She would have been 105 in a few days, and in her honor and to honor the Plant Spirits, I am continuing to pass her ways to my daughters and their daughters. When the grapes are ready, Gran will surely be watching over a gathering of 9 women & teens as we work to preserve the gifts that we have been given.

Hi MossStaceyn3! Thank you so much for sharing you wonderful story about Gran and the incredible legacy she passed on to you. How did she preserve the leaves? I’d love to hear more about the recipes if you are willing to share!

[…] O’Driscoll. D. (2022, April 16). Sacred tree profile: Wild grape (Vitis labrusca) mythology, medicine, and meanings. The Druid’s garden.https://thedruidsgarden.com/2021/01/17/sacred-tree-profile-wild-grape-vitis-labrusca-mythology-medic… […]