One of the changes that humans have experienced with the rise of industrialization, and more recently, consumerism, is a shift away from creating our own lovingly crafted objects, objects created with precision, skill, high-quality materials, and care and into using things that instead are made by far away people and machines. I wrote a little bit about this before in a post on wood. In speaking of the 17th century, Eric Sloane writes in the Reverence of Wood:

“In 1765, everything a man owned was made more valuable by the fact that he had made it himself or knew exactly where it had come. This is not so remarkable as it sounds; it is less strange that the eighteenth-century man should have a richer and keener enjoyment of life through knowledge than that the twentieth-century man should lead an arid and empty existence in the midst of wealth and extraordinary material benefits” (pg 72).

I know that a number of us on the fringes (and growing increasingly towards the center) are picking up these old skills through the process of reskilling and supporting craftspeople in their trades. The craft brewing movement, wood carving movement, and fiber arts movements are several such examples.

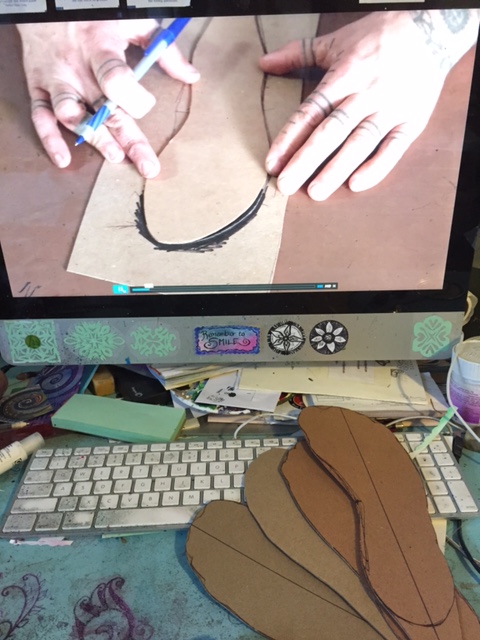

Recently, I’ve been learning a few new skills including making candles from the beeswax from my beehives, learning how to make my own leather shoes, and learning basic woodcarving techniques (some of which I’ll write about at some point). But what has struck me in the process of trying to learn these things is the lack of specialized, accessible knowledge on the subject, especially in my local area. What I’d ideally love to do is to sit with a master and learn the process from him or her here in my local community–but there are no masters to be found locally. Youtube, old books, and an occasional class where I drive a long way to learn is the most common way of gaining this knowledge these days.

And so, I wanted to step back a bit from the specific crafts, and today, spend some time reflecting upon the idea of making things as both a functional handicraft and as a bardic art that cultivates the flow of awen. I think this is important for a few reasons. For one, as someone on the druid path, supporting the bardic arts, which include various functional crafts, is an important part of that path: finding one’s own creativity and being able to do something with that creativity is central. But second, that learning how to make my own things that will last, from local materials, helps us minimize our footprint on the living earth. Third, making our own things helps me slow down and reconnect with the earth and her gifts. Plus, there is simply a lot of fun to be had in making your own shoes, paper, jams, spoons, or whatever else! (Of course, all of this requires time, which is a challenge I also wrote about earlier this year).

The Skilled Trades and Home Economy

At one time, humans in communities provided nearly all of their own needs: there were coopers, cobblers, tanners, barm brewers, blacksmiths, wainwrights, apothecaries, tailors, as well as bustling home economies that produced many other things that a family needed. A list from Colonial America offers a description of some of these jobs here. What strikes me about this list is the amazing number of specialized professions there were for making everyday objects and tools for human use, everything from brewers’ yeast to barrels, from medicines to wagon wheels. In other words, humans in a community used to make things for that community–the expertise was centered in and around that community. My example of making shoes, or the art of cobbling, falls into this category: every community had a local cobbler to make and repair shoes–this required specialized knowledge, tools, and practice.

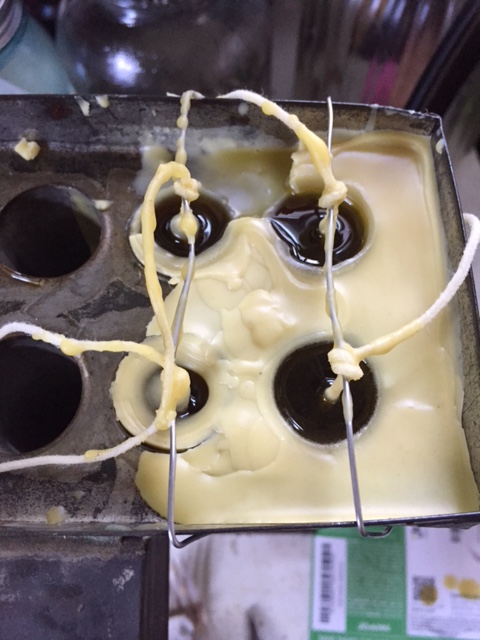

The second kind of economy in these times was, of course, the home economy. Homesteads were places of constantly bustling activity: bread baking, cheese making, tool making, farming, candle making or rush light making–providing so many of a family’s own needs. My candlemaking experiences, here, certainly fall into this category. I’m not going to talk too much about the home economy today (although I likely will at an upcoming point).

The system I outline above was no perfect system, but it was a system that employed highly skilled people working with more local materials in their local communities, making things for the use of that community; combined with highly adaptable home economies that produced the bulk of a household’s needs. This system allowed people to monitor how supplies in the local ecosystem would last and to understand their direct ecological impact when they made new things. Further, this general system has worked for most non-industrial agrarian cultures around the globe for millennia. Its especially interesting to note, too, that this system actually seemed to be less work-intensive than current systems; one such presentation of this is through Juliet Schor’s The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure and in Tom Hodgkinson’s The Freedom Manifesto. Both of these books explore the issue of work, showing how many of our ancestors had plenty of time for 12-day feasts and much revelry and worked fewer hours than we did (a topic I explored earlier this year).

Tucked into quiet places, you still may find the remnants of these locally-based, highly skilled trades: odd tailor who makes his or her own suits, the local wood turner, and so on. Today, we see the remnants of these older ways of life in antique shops and other nooks and crannies: hand-hewn and worked wooden objects, iron tools clearly forged by an expert blacksmith, homemade buckets, spinning wheels with various small repairs, handmade clothing and quilts, and so on. In fact, my town still has a cobbler who fixes shoes (but doesn’t’ make them; he tells me his grandfather from who he learned the trade from did). At a thrift store visit last year, a dear friend of mine found an incredible green suit made by a tailor right here in town (and obviously, no longer in business).

But with the rise of consumerism and industrialization, we left behind many of these skilled trades and we left behind our home economies to buy things. We also, unfortunately, left behind even the idea that craft was something to take seriously and that a high-quality product was worth paying more for or spending a tremendous amount of time to make.

The Decline of the Skilled Trades

As someone who grew up in the 1980’s and 1990’s in the rust belt/flyover zone, I have always lived in a time of declining small businesses and large corporations. Each year of my life, I’ve watched more family businesses and local shops close up for good and be replaced by large corporations on the edge of town reachable only by car (rather than in town, reachable by foot). In fact, I lived this firsthand, watched my parents’ own graphic design home business steadily lose their local customer base as one business after another closed their doors, or relocated, or were bought out by a bigger corporation who were headquartered in a far off state and not interested in offering work to local graphic designers. The first Walmart came to my area while I was still in middle school, driving many local establishments out of business within only a few years’ time.

At this point, exploring the landscape of most places in the US shows the most boring monotony of the same businesses selling the exact same things (an issue I took up last year). I had, of course, read in various places about the engineering of American society to be consumerist in the times following WWI. This general pattern was well underway long before I was born, and in fact, was several centuries in the making. To understand this phenomenon better, I spoke to some older family members to try to understand their firsthand experiences. My older family members attribute a large number of factors to the loss of our small trade businesses and creation of handicrafts locally, but I’m going to hone in on three that seemed to arise with the different conversations: 1) the rise of large corporations (which is the fairly obvious one), 2) the lack of new apprentices to carry on the family businesses; 3) the loss of the blue laws and 4) the cultural disregard for handmade things.

Obviously, when large corporations like Walmarts and Targets come to town, economics has a lot to do with the issue. For one, because they buy and ship in such bulk, they can undersell local businesses on the same products. But they also sell cheap products in snazzy packaging with fancy words masquerading as good products. This has been talked about a lot in other places and is fairly well known, so I won’t belabor the point here. This decreases the demand for these locally-produced crafts and trades.

The second reason was the lack of young people wanting to go into these traditional crafts and trades–which has a lot to do with economics, but also with interest. When my parents attended the closing of our local shoe store in Johnstown (called Yankee Shoe Repair), they spoke with the owners, who said that there was nobody who wanted to carry on their business and that was one of the reasons they were closing. They purchased a good deal of leatherworking supplies for me, and that’s how I got my start in leatherworking.

Third is my mother’s “blue law” theory. Blue Laws, which used to protect family time, also contributed to the downfall of the trades here in our region. The Blue Laws governed, among other things, when businesses had to stay closed to ensure adequate time for families and religious services. After the blue laws were removed, family businesses often kept with those traditions (and still do, in limited places) while big corporations remained open for longer and longer hours, making it more convenient for customers. Today, we are seeing the real effects of these pushes with the loss of Thanksgiving day and the push for being open on Christmas day. The limited hours made shopping at these stores (and their associated value systems) less convenient and, in an age of convenience, folks less likely to visit the family-owned business.

Finally, the idea of something being handmade (rather than store-bought) after World War II took on a negative connotation for many Americans. Handmade objects were looked down upon and seen as less desirable. My mother shared with me stories of wearing “hand-me-downs” or “handmade” clothes rather than purchased ones and how she was teased as a child. Even in my own childhood, I experienced this. My paternal grandmother was a maker, going to church sales, picking up huge bags of old clothing and drapes, and repurposing them into toys, skirts, doll clothes, and more. When I went to school with my handmade clothing lovingly crafted by my grandmother, I was mocked (which, to the other children, suggested poverty). Today, “handmade” still has some negative connotations (especially if it’s done in a less-than-sleek manner).

Problems with the Shift to Consumer Economies

So now that we have some understanding of what happened to the skilled crafts and trades, I want to briefly explore a few problems that this has created. These are key problems for both individuals, communities, and our broader lands.

The Loss of Highly Skilled Workers and Educational Opportunities. First is that the highly skilled labor required to produce these objects has shifted to mechanized low-skilled labor. This means that these highly skilled trades employing people in every community that offered a good living have now vanished. These skilled trades had offered young people educational opportunities and career opportunities through apprenticeships. Now, these positions are largely relegated to lower-skilled or unskilled factory workers in a single community (likely these days, overseas). We’ve taken 100,000+ cobblers located all over and have replaced them with 10 factories each employing 300 low-paid, unskilled employees in far off locations. Pressing a button on the shoe cutting machine is a lot different than the custom measuring, cutting, and fitting of a pair of shoes for a specific person in terms of the skill, care, and precision necessary for the work. Not to mention that you end up with a much better product if the shoe is made for your feet. Finally, a pair of shoes made in a factory vs. one made by skilled hands fundamentally changes the nature of the work we do, and I believe, makes it a lot less meaningful.

I have firsthand experience of this factory work: when I was in high school, I worked for a summer in a bra and underwear factory; we didn’t produce bras or underwear (they were made in sweatshops overseas), but we hung them, packaged them, and shipped them off to various big box stores all over the country. It was the most wretched four months of my life. At the factory, anyone could do the work; it could be learned with minimal training, usually less than a few hours. There was no craft, no care in the work–and how could there be? People worked in rough conditions, for minimal pay, and there was no need to be skilled or invest time in the quality of our work done well. This isn’t to say that people at the factory were lazy–they worked hard, but the nature of that work was much different than our skilled shoemaker fitting a person for a custom pair of shoes.

Environmental Health and Health of Ecosystems. One of the things about goods being made right in your local community is that you know what goes into those goods and where those goods come from. The local tanner and hunters have some idea of the level of the deer population; the local woodworker knows about the health of the forest; the local farmer can speak about the quality and health of the soil. When the creation of goods is removed from our vision or done on the largest industrialized scale, we no longer can assess the health of those places where raw goods are coming from nor the impact of those goods on the land. Sure, we may hear stories, but it is a “far away” problem that we pay no mind. Further, those producing goods as a family profession are going to care about the health of the land from which those goods come (and continue to come) as their livelihood depends on it. Not so with the large-scale production factory, who can often just find a new source of raw materials to exploit (this, also hidden from view from the end consumer).

The truth is, I have no idea where my goods really come from when I’m purchasing something at the store; they are hidden behind various “distributed by” labels on packaging and even writing a company often does not lead to any deep understanding. This means I can’t really assess their real costs to myself or to any community that may be involved in the extraction of resources nor production. And I certainly have no idea what the environmental costs of those goods are (and I suspect they are generally quite high).

Product Quality and Comfort. On the consumer end, the quality of the products has declined with the loss of our skilled trades and crafts; in many cases, options in many cases is to choose between low-priced junk and high-priced slightly better junk. While factories can certainly produce these objects more “efficiently”, they certainly can’t do it better or of a higher quality. Shoes are a great example here. A pair of shoes fitted to an “ideal” foot is not a pair of shoes fitted to my foot, and my feet nearly always hurt because they are different than the factory-produced ideal. I have never liked shoe shopping and it usually takes me many tries to find a decent pair of shoes that are comfortable. The factory standardizes human feet in a way they shouldn’t be standardized, and my limited experiences with cobbling have already taught me that human feet don’t come in simple digit sizes. Tracing my own and others’ feet on paper as part of learning to make shoes has taught me that feet are as unique as we are, and shoes, therefore, also need to be. Goods designed in a specific local context or body in mind are simply better than those that are not!

Variety and Weirdness. The standardization of goods also comes with the loss of diversity (and anyone who has studied evolution knows how important diversity is to any system!) A local shoemaker in one town might produce a very different kind of shoe than one three towns over depending on his/her skills, training, and creative approaches. With a factory pumping out 10,000 shoes a day that is identical, we now have much less choice, less quirkiness, and less all-around creativity.

Suffering, Joy, and the Energy of Goods. As I’ve stated on this blog before, the things that are near to us, including physical goods, bring their own energy and that energy impacts us. A shoe produced in a sweatshop invariably brings some of that suffering into your own life–it carries the energy with it from how it was extracted and made. I highly suspect that the cobbler enjoyed his or her work much more than, say, the under-paid and chemically-exposed factory worker. Whose shoe would I want to wear?

The “Real” Costs. I think the real lure here is the idea of a cheap good and its overall value. Cheap products are not better ones, ones that are of quality and that last. It’s true that Walmart and Payless Shoes other bargain stores can sell a cheap pair of shoes for $25, while the local shoemaker sells a much better and high-quality pair of leather shoes for $150. This doesn’t seem very competitive on the surface to the average consumer. However, given that the whole purpose of consumerism is to consume as quickly as possible, and so, the $25 pair of shoes you wear every day have barely a year shelf life. You’ll have to replace those cheap, uncomfortable shoes 10 times in a decade. This ends up costing far more than the $150 pair of shoes that last a decade with minimal maintenance and repairs.

Where do we go from here?

Industrialization isn’t going to go away tomorrow (and it would be very bad if it did for those of us who still depend on it). And yet, I think there are a lot of things we can do to cultivate the bardic arts, both within ourselves (as my earlier posts in this series suggested) and to cultivate a culture in which the bardic arts are valued and profitable. Let’s look at a few of those things now!

Supporting Skilled Trades

I think the very first thing all of us can work to do is to support those folks who are still around, still engaged in their skilled trades. My town has a cobbler–he doesn’t make shoes (unfortunately, I’d love to learn from him!) but he does repair them, and I’ve been glad to visit him every few months with small shoe repairs. I honestly know enough about shoemaking at this point that I could manage some of the repairs–but I want to give him business (and his repairs will be nicer than mine!) There’s a local wood turner who I’ve been buying wooden bowls and plates from, and so on. The more we can seek these folks out and help them thrive, the better. On the more fine arts side, the same thing applies: finding local artists, local theaters, local musicians, and supporting their work as much as possible. Each town and community has its own quirky, unique scene of great people creating great things, and supporting that work is so critical to returning to a bardic-arts enriched culture.

Reskilling, Time, and Community

We just don’t have time like we used to have to engage in these functional crafts; our ancestors who were making these things in pre-industrialized cultures had a lot more time to do so. (Pre-industralized cultures worked a lot less and played a lot more than people do now). The time and “productivity” suck we are all facing means that we simply don’t have the life energy to really invest in these skills and get good at doing them. I feel this really harshly because I have lots of things I want to do–a wide variety of skills to learn and master–and more often than not, I’m exhausted with my work (and paying off those darn student loans) and don’t have the energy or time to do many of them. This is a cultural problem that faces anyone who is trying to earn a living within our current system.

I think that this time crunch we are all facing means that we don’t necessarily have the energy to figure things out or to fail in order to learn. The way we learn as humans, even when there is someone teaching us, is by trying, testing things out, failing and re-trying, and fiddling with things till we get it right. It’s like a slow spiral, working ever inward and deeper. We need a lot of time to hone our crafts, to take them from beginner attempts into things that are functional that we can be proud of. This means we have to invest a lot of time in them–the one thing that we don’t currently have. Without investing time, we can’t get good at them and turn them into art.

Still, these skills are worth doing and worth preserving, and finding ways of doing so (living arrangements, working arrangements, defending vacation time, etc) are important things we all need to figure out how to accomplish.

My solution at present to this is twofold. For me personally, it is a matter of making the time and keeping with it. I’m working to make the most of the small amounts of time that I might have available (e.g. stitching up a hand-bound book while talking with friends or waiting for my car to be repaired, similar to what knitters do). But also, setting aside sacred days and times to do that work.

The second is community–I’m working hard to find friends to learn these skills with and working on building a network of folks who have different skills. Like the mini-villages of old, finding people who can teach and who are willing to trade is a great way to keep these old skills alive and vibrant. And so I have a friend who carves spoons, and we trade for artwork, another friend makes really great jams, and so on.

The third is to pick a craft and really hone it. I’ve been such a dabbler for a lot of my life, and I really want to start making a few things and doing those well. I’ve suck with my painting and writing longer than anything else, and the results of those efforts show. I’m really getting into leatherworking and some primitive woodworking, and I know those skills will both take me years of time to develop and master. These seem like enough: both in term of the time investment, but also in terms of the materials/tools investment (which is considerable). But picking one, or two, and really working at it is important.

Reskilling and Preserving Living Knowledge

As I’m involving myself deeper in my own reskilling, I’m also seeing the serious cracks and edges of this movement from a knowledge perspective. While knowledge of how to do many things used to be widespread, local knowledge about many of these more complex skills seems to be absent almost entirely. Skilled knowledge about these things may be out there in the world, but it is often contained in small pockets, or inaccessible in faraway places, or offered only at considerable cost (I could travel to a master shoemaker and learn, but it would cost me over $1000 to do so). Or, knowledge is contained in good books, many of which are out of print.

Another issue with this is that many of us no longer have this knowledge or access of where to find it, and we are learning a little bit and bumbling about in that learning and sharing what we learn. But the truth is, you can’t just replace a master craftsperson with a short online tutorial and expect the product to come out the same way. I am learning this the hard way with shoemaking–I tried what looked like it was a decent online tutorial, but my shoes didn’t really come out and the key aspects of the tutorial I needed were lacking. I invested in a Kickstarter campaign to learn from a master craftsperson and his course is incredible and detailed–and I’m putting the finishing touches on my first pair of custom shoes!

And so, in terms of reskilling movement for more specialized skills, we need to continue to build first-hand knowledge. I think it would behoove us to seek out the teachers of these kinds of skills, learn from them, and work hard to pass it on and to keep those traditions alive. I can’t stress this enough–seek these folks out, learn from them, document that knowledge, share it, and preserve it. The internet is great for this! Share, share, and share!

Localizing Resources

Another strategy that you might try to start bringing more handcrafted functional things into your life is looking at what resources already exist in your community or local ecosystem. Here, there are always places being logged, and those loggers leave behind so much good wood. Straight branches, curved interesting pieces, green or drying out. This is part of what prompted my interest in woodworking: the materials are so abundant and easy to find here that it seems that all I need is to put some time and hone the skill of doing it.

I have a friend who makes these incredible pieces of art from buckthorn vines in Michigan. Buckthorn is everywhere in Michigan, and townships often have clean up days where they pull them out and burn them. She takes them home and turns them into baskets, picture frames, and more. My other friend, Deanne at Strawbale Studio, uses the clay, sand, and silt in her soil combined with phragmites reeds to make houses and natural structures. Again, she is capitalizing on resources that are already present there in the landscape. Yet another friend has cultivated abundance by growing bamboo for flutes and whistles!

So rather than picking a hobby that requires you to bring resources in, perhaps look at what resources are there and use them, if you can. This is the best synthesis of nature-oriented spiritual practice and the bardic arts and crafts.

I think that the edges are starting to wear thin for a lot of us concerning the lure of consumerism with its flashy gizmos and cheap gadgets. It’s exciting to see the rise of the reskilling and maker movements, where people are realizing the potential of their own creative gifts and working again to create functional and lovingly made crafts. I think that many of these movements are not yet mainstream (perhaps craft brewing and the tech/maker movement being the most mainstream at this point), but I do see them as gaining momentum, at least among the fringe groups focusing on sustainable living, permaculture, transition towns, and the like. While this post explored some history and problems, our next post will continue to get us deeper into the relationship of the self with the idea of craft and the bardic arts–and how we can embrace this work as part of our own spiritual and sustainable path.

I love your article and agree with what you are saying, however, sometimes we are “landlocked” so to speak and have no place to go for resources because either there are no natural resources for what you want to create or no stores in which to purchase those resources nor people willing to being in the supplies saying “no one is interesting in buying this stuff (even though you could keep them in business with your orders alone!) . What happens then? I would love to move but can’t afford to go where my supplies would be plentiful so I must rely on the internet for them.

Hi Snowfox, I’m not just talking about natural resources, but any abundant resource. Disgarded plastic, old bags, whatever is abundnat and in your ecosystem! It was one of many other suggestions–but a lot of us still end up getting some stuff online for sure :). Thanks for reading!

thank you for the info. 😀

Re-purposing helps a great deal! I salvage parts from all over, a motor here, light fixture there… Anything of use, especially solar! Once I have some pieces, I see what can be done… Sometimes its a repair job, a tweak, a new idea or just being cheap with my purchases (I just recently re-purposed a pile of wood and T8 LED’s into a gardening cabinet for winter growing and self-sufficiency

I also enjoy making staff making and some pyrography… This is the only part I rely on natural materials for, but even in the city, its not difficult to locate trees being trimmed or fallen branches after a storm

Love the winter gardening cabinet idea :). And yeah, I’m surprised how easy it is to find natural materials, even in urban environments. There always seems to be some pieces of wood on the curb, some tree trimming or downed branches, and that opens up a lot of possibility.

Thanks so very much for posting this, Dana. For years I’ve bemoaned the fact that we throw away watches (for example) and buy new ones, instead of going to a local watchmaker for repairs.

One of the “in” movements now is DIY crafts with people posting that they’ve found discarded items and repurposed them with a bit of spiffy paint,etc. The motives may be for show and bragging rights, but I’m encouraged by this trend.

My husband and I are clearing out accumulated items (junk) in anticipation of a retirement move in a couple of years. We have donated much, had a garage sale, and have given away old toys to youngsters. Much still needs to be done, but I feel good about the process.

Thanks, again, for the post. These are awesome suggestions and great reminders!

Oh yes, repurposing is a huge thing these days! I have this great purse that someone crocheted from bread bags :). We certainly have an abundance of junk, so why not use it?

I’m glad you are feeling good about slimming down the accumulated stuff. Multiple recent moves have had me continue to pare down, which is a very nice feeling and experience :).

Reblogged this on Rattiesforeverworldpresscom and commented:

Love your article 🙂 I make my own cosmetic and all cleaning products, laundry products, soap, etc they are all natural, I know what I put in them and I like them, I make some for friends too. I love buy handicraft products for decoration, calendar , … I cook everyday and I don’t buy some industrial prepared meals. I’m not able to make some clothes, shoes, furnitures 😉

I’m learning a lot of new things now. I’m trying my hand later this year possible at learning lashing for furniture making (although it is kind of intimidating, I still want to learn!) But it sounds like you are making a ton of great stuff 🙂

🙂

Another good read. Where I live, we have an embarrassment of riches in farmer’s markets. I’m not kidding, we have around 6 that I can easily access on either Saturday or Sunday, and a seventh that is the next city over. Many are small and intimate, with sellers, crafters and vendors I have gotten to know over time. So I count myself extraordinarily lucky. It’s made me conscious of the term “local” which is bandied about too easily. I’m sorry, but in Minnesota, coffee beans are not “local.” The roastery may be local but they still had to source the beans from the equatorial regions, and someone had to grow them and harvest them etc etc etc. So as far as I am concerned, “local” has become meaningless, just like “natural” or “all-natural.” This is the sign of corporate takeover of what started out as a movement to reclaim something we used to value, the same pattern over and over, in which real people recreate something of real value that eventually becomes co-opted and ruined as corporate interests take note and horn in to rake in profits. Mass-produced and factory farmed chicken hereabouts is billed as being from “local, family farms.” Such a bright shiny lie that people fall for. Educating people in the differences is exhausting, and ordinary people are strapped for time, energy and money so they opt for the convenience of Mall Wart and the rest of the big box chain stores. it’s a lot like eating fake food all your life and then being surprised when you get sick from unusual degenerative diseases that could have been prevented by eating real food; if you had made the connections earlier, and made the effort to source real food and prepare it, you’d stave off a lot of future problems.

Or, more succinctly, “Pay the farmer now, or the doctor later.” (I can’t take credit for that pithy phrase, I’m sorry to say!)

I actually have a t-shirt, given to me by one of my best friends, that has that exact saying!

I was having this same conversation with a farmer friend this week at our permaculture guild meeting. This is a new farmer and a young female farmer, and she said it was so bad trying to sell organic produce in a place where people don’t even really get the “local” thing. Some locations have local movements, but so far, our little town does not. This means that people don’t really understand how it bolsters the economy and gives stability–so it is a hard road to walk. I think, in time, the farmer’s markets will continue to prosper, even in places like this!

Great post! Handmade items are REALLY important. When a person makes something from scratch / by hand, they are literally putting their time, energy, and LOVE into the object.. So when you wrap yourself in that quilt that your great great grandmother made completely by hand, you are literally wrapping yourself up in a shield of love. And THAT is a priceless thing these days. Love will shield you from all the evils of the world…

It is so true. I love the idea of the quilt as a shield of love. I think a lot of handmade objects are like that–they offer us strength, power, love, stability.

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Thank you, Dana, for this post! totally understand all you are saying – I’m old enough to remember things before the mass industrialization of the ’60s and ’70s – I had older relatives who could still do craft-type things, who knew how to “make do or do without,” as John Jeavons put it. Sometimes I am sad that younger people have no memory to fall back on of how things were before, like the more diverse bug population in my part of central Indiana. It’s rare one sees a Cecropia moth, yet in my childhood, there were enough for every kid who went through 7th grade to collect one for biology class. I greeted a praying mantis in my back garden bed yesterday, whose presence felt magical, because mine is the only pesticide-free lawn on my side of the street in a small town (fortunately, I have two neighbors across street who are not druid types, but just have enough sense not to use chemicals – they’re my age group!)

Do you know someone who could use some leatherworking tools? My husband George passed away 5 years ago, and had a set of some tools that he had used some time ago, before we married, and I’ve tried to donate his things to people who’d value them, and local thrift stores are too anonymous for my taste … It’s just a small box worth, but something!

On Sun, Jul 23, 2017 at 8:30 AM, The Druid’s Garden wrote:

> Dana posted: “One of the changes that humans have experienced with the > rise of industrialization, and more recently, consumerism, is a shift away > from creating our own lovingly crafted objects, objects created with > precision, skill, high-quality materials, and care and” >