What can we do to support nature in this age that is meaningful and important? One of the primary ways that I’ve been thinking about this is in terms of creating refuges for life, or “refugia.” I’ve shared some of these ideas before in various ways as I’ve developed them on this blog, but today’s post offers my most comprehensive overview and a thorough guide of how to create refugia and the resources to do so–and I’ve now been doing this for 10 years, so I have some new things to share! In fact, this year, I’ve been giving a series of workshops and talks on refugia gardening, particularly geared towards those who have gardens or are herbalists. You can also see resources for my talks on this page which include a number of photographs and examples from my gardens, handouts, and more information! Thus, this post is adapted both from my workshops, from my Land Healing book (whic contains even more information than what is here), from my the Plant Healer Quarterly column “Roots, Shoots, and Spirits” and also from watching my planted refugia mature and grow. My goal is to offer a comprehensive introduction to the practice, complete with examples from my own ecosystem – USDA Zone 6A in Western Pennsylvania, USA (this means we have winter conditions with no more than -10, and that’s quite rare. Our growing season goes from mid-May to the end of September and we are in a temperate climate).

Introduction: Why Create Refugia? How can I help?

One of the many things that we think about as herbalists, druids, and gardeners is how to bring healing and support to nature, from which all of our medicines, food, and resources come. Thus, many of us are concerned and want to take action on the overharvesting of plants, an increasing number of medicinal plants that are in peril, and the degradation of our ecosystem. In today’s article, I want to share a technique that I call “refugia gardening” that can work to support our ecosystems and medicinal plants in very specific ways, creating small pockets of intentionally supported life to survive this challenging age. This is a very hopeful, impactful method of protecting and preserving nature, and as I’ll argue here, possibly one of the best things we can do at present to protect the natural world. It can be a supplement and extension to what many of us already do in growing medicinal herbs or in other conservation-based work.

Refugia or “fuges” are a natural phenomenon discussed by E. C Pielou in After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America (1991) among other places. Refugia are small pockets of diverse life, sheltered from the larger devastating effects of the last ice age. While broader populations of species died off, these isolated pockets of life survived as a sheltered spot, a microclimate, a high point, and so on. When the glaciers receded and left a bare landscape devoid of topsoil or most other forms of life, it was these refugia that allowed life to spread outward again, repopulating areas in North America that had been covered with glaciers. Of course, Refugia are not limited to North America–they are a worldwide phenomenon, and even our human ancestors, at various points in our history, have used them to survive challenging environmental conditions. Further, climate science is now recognizing what are called climate change refugia. Morelli and Millar (2018) describe these as ecosystems that are more resistant to climate change, which can house more biodiversity despite broader inhospitable conditions. These ecosystems might be those microclimates that help build climate resistance such as canopy cover (to regulate maximum and minimum temperatures), areas with deep lakes or snow that are heat sinks, and so on. In both of these related examples, we see a situation where pockets of biodiversity can thrive a larger inhospitable situation.

In the Anthropocene, a time of human-dominated ecological changes, we have an increasingly dire situation that is not that ecologically dissimilar to the last Ice Age. Along with tremendous loss of biodiversity, human population increases mean that humans are taking up more and more space and demanding more resources from the earth. Combined with climate change, these pressures can create an increasingly inhospitable landscape for most species. For example, in the United States alone, we have at least 40,000,000 acres of lawns, 914,527,657 acres of conventional farmland, and 40,576,000 acres of urban areas—all of which are inhospitable to the bulk of species that used to occupy these spaces. We also have 539,136,000 acres of forests, but the bulk of this forest cover is often subject to resource extraction and human-driven pillaging, making these areas a lot less diverse than they once were. For example, the loss of American Ginseng, Black Cohosh, Ramps and other woodland medicinal species in most of the Appalachian Mountains is caused both by so-called ‘sustainable logging’ and human overharvesting—so these forest areas are not the pockets of safety they may have once been for woodland medicinal plant species. In fact, here in the US, our forests are losting biodiversity due to ongoing demands and pressure by humans. Places that aren’t being actively pillaged by humans are likely are recovering from previous resource extraction or are subject to other duress–and the few spaces that are supposedly “safe” and “protected” are constantly under threat from new bills or legislation, logging, mining and so forth. And so, we have a situation where a biological life in the broadest sense has a lot less space to grow and thrive unhindered. It is these factors, and many others I have not named, that are driving the sixth mass extinction-level event on this planet.

That last paragraph was hard to write, and I’m sure it was hard for you to read. But rather than turn away from this information, the question becomes: what can herbalists and druids do about it? We can create herbal refugia, of course! A lot of us don’t have control over what is happening in the land around us, but we can work to help cultivate small spaces of intense biodiversity, spaces that preserve important plant species, then we can put more of the building blocks back into nature’s hands for the long-term healing of our lands. This allows us to grow herbs and tend green spaces—and do good for all life. Thus, I would like to suggest that each of us, as we are able, create biologically diverse refugia as part of our herbal growing practices–small spaces, rich in diversity and life, that can help our lands “weather the storm” and a place where we can grow seeds, nuts, and roots to scatter far and wide. Or if we are already cultivating biologically diverse gardens, homesteads, nature sanctuaries, and the like, we add the goal of becoming refugia to our plans–and plant accordingly. In the rest of this article, I’ll share some strategies you can use to start to plan and create your own refugia.

Creating Refugia: Land and Where to Cultivate!

The first thing you need to get started creating refugia is a piece of land that you believe is reasonably safe from human resource extraction or future human-caused damage—for many herbalists, this might be our own herb garden, property, community spaces that we help tend, or protected places where we volunteer. In terms of land, refugia can be created anywhere, including in more human-dominated spaces (like lawns), or in more wild spaces (forests, prairies, wetlands, etc.). You will note that I emphasize land that is “safe” here because what you will essentially be creating is a lifeboat or sanctuary—a place where nature can thrive, grow, and survive in this difficult age. You don’t want this sanctuary to be created only to have someone else come in and destroy it a few years after you establish it.

You may already be engaged in extensive gardening of herbs, perhaps using organic, biodynamic, or permaculture-based practices. As someone who practices herbalism, organic gardening, nature spirituality and the like, you likely have a multitude of goals for this space—foster life, grow and create medicine, have a place that is a personal refuge for yourself, have a place for spiritual practices. Or perhaps you do a lot of wild medicine foraging and know many areas that have some level of protection and could use some caring human intervention. Or perhaps you are looking at a large swath of lawn in your backyard, knowing that it could be so much more. For an existing or new space, you can add and/or compliment your existing approach with a mindset towards creating refugia.

Long-term safety and protection here is an important goal, and one I had to, unfortunately, learn the hard way. Prior to purchasing my own land, I began working to gather and spread a variety of woodland medicinal species (a personal goal of mine for refugia creation) in local forests. The forest I targeted was state-owned, part of our state forest system. Thinking that these lands were safe and protected, and had a perfect habitat for our region for a range of woodland medicinal species, I scattered seeds and planted roots of American Ginseng (panax quinquefolius), Blue Cohosh (caulophyllum thalictroides), Black Cohosh (Actaea Racemosa), Ramps (allium tricoccum), and Red Trillium (trillium erectum). My refugia and efforts were going well, and then a few years later, I was devastated when a large portion of that forest was “sustainably” logged. I put sustainably in quotes because in quotes because modern logging methods are not sustainable, for many reasons, including the fact that heavy machinery disrupts the forest floor, crushing many of these plants with their medicinal roots. Almost nothing I had growing survived the machines. Since having this experience, I’ve spent a lot more time studying what lands are fully protected from logging and which ones are not, recognizing that many public lands are just as subject to pillaging as private ones.

Of course, what else matters is the specific kind of ecosystem, climate, microclimate, and habitat you have or can create. For example, where I live in Western Pennsylvania, we have a range of different species that are at risk, but due to the nature of my own land, I can’t create refugia for all of them because I can’t create the right habitat conditions for them to flourish (e.g. mature oak forest vs. woodland marsh vs. full sun field). Each refugia needs to be unique based on the nature of the ecosystem you can foster.

The next set of steps have to be done together before you can begin to plant: setting goals, examining the long-term climate projections, understanding what species might be at risk, and creating a list of plants and species you want to target. I’ll share about each of these individually now.

Creating Refugia: Goals

Setting goals and visioning can be an important step as it helps you articulate how you want to proceed and target specific plants or plant species as part of your work. Goals should be simple, direct, and attainable—you can look at your goals and see how you are doing to assess your progress. Another point about setting goals and intentions is that you can invite the land itself into your planning and conversation. Tell the land where you hope to build a new refugia garden what you intend, sit with the land, and see what images or feelings come to you. These can be very powerful in helping you move forward in the best, most reciprocal way possible.

After my devastating forest incident and purchasing a new piece of property, I began developing two refugia: a woodland medicinal refugia site using permaculture principles and sacred gardening practices and a full-sun herbal refugia. Your goals might be different depending on your situation, but I thought I’d share mine as a good place to start.

The woodland refugia garden will contain plants that:

- Native to my region

- Medicinal in nature

- Rare, endangered, at-risk or non-existent in the surrounding ecosystem.

- Slow growing or hard to establish.

- Once established are able to grow without much human influence or cultivation in the long-term (perennial focus or self-seeding annuals).

- Are well positioned in terms of how my climate will be changing in the upcoming century.

The refugia will be:

- A teaching and demonstration site for others

- A site of peace and beauty

- A sacred place for humans to commune, reconnect and grow

- A site of ecological diversity and healing for all life

- A site of healing

Given this example, you will want to spend some time thinking about your own long-term goals and what you are seeking to accomplish. In other words, what good do you want to do on behalf of plants and other species? Be bold and be brave. The earth needs you!

Thinking Long-Term and Examining Climate Projections

Since we are thinking long-term with refugia gardening, I think it’s a wise idea to look 10, 20, or 50, or more years down the road in terms of climate change. How will your immediate climate change in the upcoming century? Will it get hotter, wetter, drier? Are there species that are rare/at risk, but well adapted to these changing circumstances? Usually, these resources exist and can be found online.

The United Nations has a range of useful reports and assessments, which you can find here; additionally, the US Environmental Protection Agency offers global climate risk assessments. A more technical document is NASA’s Global Daily downscaled projections. Finally, each state in the USA may also produce a specific guide, such as the one I drew upon in my own state of Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania state guide provided exactly the information I wanted to know to do more long-term planning (about temperature, weather, snow cover, and more–as well as about different emissions scenarios).

Going back to the Climate Refugia concept I discussed above, knowing how microclimates can affect the overall stress on the ecosystem is also helpful to understand. Certain kinds of microclimates can better insulate your efforts from long-term impacts, so you can see the US Forest Service’s information here. You might consider how building in some of these features or using existing features may help you.

While the resources and information can be difficult to read in this section, it is necessary because it allows you to engage in longer-term thinking. This is thinking not only about what conditions exist today but how you can plan for the future. This is important—if you are going to be in an area with water or heat stress, considering that in your planning now can help you address challenges later. Because knowledge is power, and your whole goal is to create a lifeboat for life to thrive despite these circumstances.

Since much of the planet will be undergoing water and heat stress in the future, the other thing you might think about here is how your refugia can be resilient and respond to increasing climate stress. I strongly suggest using a range of nature-honoring practices tied to permaculture design: approaches like building swales (ditches or low areas for water catchment) and using hügelkultur beds (described below) are two that allow much more moisture to be held in the soil than traditional garden beds or raised beds.

Selecting Plants and Species

Now we move to thinking about the specific plants that you want to plant and the kind of species you want to protect. Given your specific context and the kind of ecosystem and microclimate you may have access to and/or want to create: What are you interested in preserving and protecting?

In this step, it can be helpful for you to explore some of the specific at-risk species that you may want to target. You can find this information from a few sources. First, the United Plant Savers (UPS) keeps a UPS “Species at Risk” list. I find this to be a primary source of great information for the kinds of medicinal species I want to support, and most of my own lists are drawn from the UPS. On a more global scale, the ICUN Red List is the most definitive and provides information on almost every species in the world, showing if the populations are stable, increasing, or decreasing. The ICUN’s list is global, so you may also want to see if your state or region has a list. For example, where I live, Pennsylvania keeps a specific list, which was also very helpful. My own state has 763 species on our rare/endangered/threatened list, and 582 of those are plants!

Using these lists, you can get a sense of exactly what is threatened or endangered and then go from there. One reason a state-specific or region-specific list may matter is that protections may be in place for certain species. If at any point in the future, if your refugia is threatened (say, someone wants to put a pipeline through your property or some other horrific act) you may be able to draw upon these threatened lists to protect your land. This is why in addition to many woodland medicinal species on the United Plant Savers list, I also help protect some other woodland species that are critically endangered in Pennsylvania, such as the Appalachian Violet (viola appalachiensis) which is listed as threatened in my state. In other words, think as strategically as you can to address to only growing climate conditions but also human and social conditions.

The other important piece of information here is to draw upon your own experiences: your observation, interaction, and experiences in the natural world. Have you noticed a decline in certain species, even if they aren’t on a list? Which species are calling to you to be protected, supported, and nurtured in this way? Do you have a special place in your practice for some endangered herbs? For example, in our full sun refugia garden, we include New England Aster (symphyotrichum novae-angliae) and Common Milkweed (asclepias syriaca) even though they are not on any of the above lists. I do this because when I was a child, I remember these plants being extremely abundant in my ecosystem, and as an adult, I’ve noticed a considerable decline. In fact, New England Aster is almost impossible to find now in my local ecosystem, and I believe this has to do with the way that Pennsylvania manages roadsides (with chemical sprays over mowing). The other thing about these two plants is that both also support a range of insect species, nearly all of whom are also at risk. Thus, these are plants that I seek to preserve and protect.

On my own protection list, I also include the hardwood nut tree species, many of which we have mature on our property, but some others that we’ve planted. This is because we have so much logging in my area and these species are often at risk—even in so-called protected lands. In fact, the US Forest Service is proposing to log 2700 acres of primary White Oak in the Wayne National Forest, claiming that the white oaks will grow back and it will be good for the ecosystem (which is utter bullshit!). The Ohio Environmental Council which is suing the US Forest Service, has provided ample evidence that White Oaks will have difficulty growing back in the next 10-20 years due to climate change and other environmental factors. This is a great example of how paying attention locally and regionally can provide you with additional information that you can use to create your own lists.

Finally, you should observe carefully what is already in your ecosystem so that you can support those plant species that are at risk that are already present—and work to cultivate more of that species. For example, when I moved to my current land, as per permaculture design’s suggestion of observation and interaction, I spent a full year identifying and observing all of the at-risk species that were already growing in our forest. And I found quite a list: Wild Yam (dioscorea villosa), many hardwood nut trees, Swamp Milkweed (asclepias incarnata), Lobelia (lobelia inflata), Red Trilium (trillium erectum), and more. On the property, we observed carefully the exact growing conditions of these plants, and then we can propagate them, protect them, and nurture more into being. This also allows me to understand what related species may also grow well in our environment. Finally, I observed the land overtime—last year, Ghost Pipe (monotropa uniflora) began growing in an area that had been heavily logged—the forest has regenerated enough to bring this sacred medicine back. By doing this critical observation work, you can support existing plants and trees that may already be present.

Three Refugia Garden Examples from Pennsylvania, USA

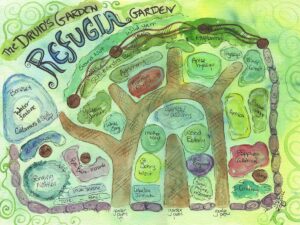

At present, my gnomish partener and I are cultivating a five-acre refugia with distinct areas—one in full sun as part of our medicinal herb garden, which serves also as a primary demonstration site and place to harvest and grow many herbs for my herbal practice. The second one is in the four acres of forested areas that we are working to regenerate; the previous owners of our property did “sustainable” logging and we are working to replant and also control the number of opportunistic species (especially multiflora rose) that are taking over the open understory. The property sits on a slight eastern slope in the Pittsburgh Plateau, an area that is part of the Allegheny Mountains as part of the broader Northern Appalachian mountains. I am currently in the USDA Zone 6A due to being in a lower elevation (1400 feet).

Full Sun Refugia Garden. The specific site was created from a circular area where the previous owners had put in a swimming pool, so it is level and round, with no existing topsoil, only subsoil consisting of heavy clay. Thus, we used in-ground hügelkultur garden beds which help hold considerable amounts of moisture due to their high woody content. Hügelkultur beds are a technique promoted by Sepp Holzer in Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture and involves either creating mounds or digging down under the soil to pile up woody material (logs, sticks, leaves) and then covering everything with a thick layer of compost. As these beds break down, they have the capacity to retain a lot more moisture than conventional garden beds (in ground or raised bed). I did this because our region is already experiencing climate extremes and we’ve experienced moderate drought and increasingly hot days, so creating ways for the soil to hold more moisture is important. Our in-ground hügelkultur beds have been performing well since we created them six years ago, holding much more water and withstanding our increasingly hot climate. This demonstrates an important principle in refugia gardening—using whatever tools are necessary to create a very resilient garden or ecosystem that can thrive in the present and future conditions.

In my full refugia herb garden, I was especially invested in supporting insect life (including significantly declining bee and butterfly species) and growing enough plants and seeds that we could give them away and spread them to others freely. I also have abundant annual and perennial vegetable gardens around the refugia, so having a space for pollinators to thrive is also important for my food growing and self-sufficiency goals. I am primarily surrounded by conventionally farmed fields, and so supporting the insect populations as a lifeboat is also critical goal. Some of the plants we grow in our full sun refugia include:

- Echinacea (echinacea angustifolia, echinacea pallida, echinacea purpurea), United Plant Savers (UPS) at risk list

- Common milkweed (asclepias syriaca), Pollinator and butterfly support

- New England aster (symphyotrichum novae-angliae), Local decline

- Swamp milkweed (asclepias incarnata), UPS at risk list

- White sage (which we grow in pots to bring in in the winter), (salvia apiana), UPS at risk list

- Arnica (Arnicaspp.) UPS

- Echinacea (Echinaceaspp.) UPS

- Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa), PA DCNR

- New York Aster (Symphyotrichum novi-belgii), PA DCNR

- White Heath Aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides), PA DCNR

In addition to these, I have planted a wide range of medicinal plants with long-range of bloom times for insect life, including during the summer nectar dearth.

Woodland Refugia. Four of our five acres where I live are wooded, and I’ve worked to create a larger woodland refugia in these areas as a primary part of my regeneration work and reciprocation practice on the land. Since the land was logged seven years ago prior to us purchasing the property, I’ve done a lot of preparatory work, clearing or cutting the remaining log debris (cutting it so it can be on the ground and decompose faster), and/or using the cut logs to creating hügelkultur beds on the edges of the forest. I’ve also done tremendous work in replanting the understory. At present, I support the following plant species

Plants: Woodland

- American Ginseng (panax quinquefolius), *UPS at risk list

- Appalachian Violet (viola appalachiensis), Pennsylvania Threatened List

- Black Cohosh (actaea racemosa), *UPS at risk list

- Bloodroot (sanguinaria canadensis), *UPS at risk list

- Blue Cohosh (caulophyllum thalictroides), *UPS at risk list

- Ghost Pipe (monotropa uniflora) *UPS in review list

- Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) – UPS

- Green and Gold (Chrysogonum virginianum) – DCNR PA Endangered

- Ladyslippers – (Cypripedium reginae, aurentiana, ennesseensis) – DCNR PA Threatened

- Lobelia (lobelia inflata), *UPS at risk list

- Mayapple (podophyllum peltatum), *UPS at risk list

- Partridge berry (mitchella repens) *UPS at risk list

- Ramps (allium tricoccum), *UPS at risk list

- Solomon’s seal (polygonatum spp.) *UPS in review list

- Stoneroot – Collinsonia canadensis – UPS

- Trilium (trillium grandiflorum, trillium luteum, Trillium erectum) *UPS critical list

- Wild Cherry (prunus serotina) *UPS in review list

- Wild Yam (dioscorea villosa) *UPS in review list

Tress – Woodland at risk and endangered species. Part of this work is not only introducing these species but also making sure opportunistic species (like Multiflora rose) don’t take up all the space for someone like Nannyberry or young Chestnuts!

- Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis, humilis, obovalis, sanguinea) – DCNR PA Threatened

White oak by our creek - Slippery Elm – Ulmus rubra, UPS

- American Holly (Ilex Opaca) – DCNR PA Threatened

- Nannyberry (Viburnum cassinoides) – DCNR PA Endangered

- Blight-resistant American Chestnut – Castanea dentata, largely expatriated but making a comeback!

I also include a number of hardwood nut trees on our list because, as I’ve described, logging practices in Pennsylvania make these highly sought after trees are harder to grow back after logging. By having mature hardwood nut species, I can take seeds and seedlings into wild areas and plant them, helping to re-establish these species that have been logged. I can also give these away at my plant walks so that others can plant them and propagate these critical species.

- American Hazelnut (corylus americana)

- Bitternut Hickory (carya cordiformis)

- Butternut (juglans cinerea)

- Northern Red Oak (quercus ruba)

- Shagbark Hickory (carya ovata)

- White Oak (quercus alba)

- Sassafras (Sassafras Albidm): Native tree, good habitat

- Paw Paw (Asimina triloba): Massive amounts of fruit for wildlife – I add this last one as we are on the northen edge of the range of this tree, but as the climate grows warmer, PawPaw is going to continue to move further north!

Part-Shade Wet Forest Garden: Part of our land has full or part-shade wetland and a pond, so we are working to restore the forest wetlands with some of the pond edge with the following:

- Shrubs and bushes

- Highbush-cranberry(Viburnum trilobum) *PA Threatened

- Wetland edge plants

- Spotted Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum) *PA Threatened

- Sweet Flag (Acorus calamus) UPS, *PA Endangered

Watching Your Refugia Grow and Learning from the Process

In the 10 years I’ve been doing this practice, I’ve learned some things! The first is that not all plants want to grow in all places. You can do your best to address sun, soil, and moisture needs, but some plants are just going to take better to your land than others. That’s ok. I’ve tried to plant a wide range of plants and also plant them in multiple places. Then see how they do, how they grow, and how they thrive. Eventually, I learn what grows really well or how to protect/cultivate further those that need extra time or support.

The second thing is that raccoons are trouble–so pay attention to your nocturnal predators and those who might stir up mischief! There was a year I planted literally 100 black cohosh roots + some fiddlehead ferns and ginseng roots. I went back to check a few days later and almost EVERY root was dried up, dug up, and destroyed! It was the coons. What I now do is put everything in a pot and get the roots established very well, and then transfer them into the rich soil in the fall–the raccoon can dig up a small root easily but not a whole plant. We have a good relationship with the coons on our property and we are friends with them, but they still make mischief!

The third thing is that there are external forces that you sometimes can’t control. Smoke from wildfires, right-of-way issues, and so forth. A refugia my parents and I were cultivating where I grew up was destroyed with the township putting in a septic line. We dug many plants and actually moved them to our home here, about 35 min away. It was devastating but we were able to preserve life and now we have more growing on our land. But actively watching out for external threats is always part of the journey.

While this is primarly on physically growing refugia, there are a wide range of ceremonies and rituals you can perform to support the land for healing and blessing. I’ve shared some of those ideas here, here, and here!

Doing Good in the World: Refugia Functions and Outcomes

The refugia garden is not only a medicinal herb garden or food forest, it is something much, much more. On a personal level, it feels good to create such a magical place of healing and support of nature. Refugia are places where we can spend time to enjoy getting to know these plants, many of which are hard or impossible to find in the surrounding landscape. It is a place that is biodiverse, alive, and welcoming. First and foremost, by doing this work, it allows us to return to our true human purpose, which Tyson Yunktaporta shares in Sand Talk is to be guardians and caretakers of the earth. Further, a refugia garden can have so many different functions and outcomes that can support your ongoing herbal practice.

Second refugia gardening can be a wonderful way to educate people about plants and the importance of taking an active role in conservation. Make your refugia garden a place where people can spend time in, learn about medicinal plants and conservation, and learn how to create them for themselves. For example, if you regularly host visitors on your land, you can add some signage or offer tours to share the work you are engaging in terms of species preservation. You can share any extra plants or seeds you have with visitors so they can start their own gardens or repopulate the broader landscape.

Third, refugia gardens are seed arks, that is, little places where biodiversity and life can spring forth once again. Once your plants are well established, you will start producing more new plants, root cuttings, and seeds than you can use, and thus, you can then to grow, sell, give away, and scatter seeds, nuts, and roots far and wide. This is nothing new–taking seeds from wild plants this year and spreading them just a bit further or into new areas is something that herbalists have done since the dawn of time. And this approach allows you to do it just a bit better, with more intention and joy. The refugia garden makes it easier to engage in the practice of wildtending–you will have an abundance of seeds, nuts, roots, and so on in a few short years or less that can be scattered to bring biodiversity back to areas that need it due to human causes like logging, mining, pollution, and so forth.

The seeds can be shared with others and spread even further though various plant education and herbal education opportunities—opportunities you are already likely engaging in. For example, I always take my seeds that I am particularly keen to scatter to my edible and medicinal plant walks, which I teach each year in my local community. Each participant at the walk has a chance to take some baby plants or seeds home with them, to scatter and give away. Similarly, in doing local plant education with children, I’ve taught many people young and old how to make seed balls. Seed balls are simple to make, where you take clay and soil, put seeds in, form a ball, let them dry out, and then start spreading these balls far and wide. Twenty-five children armed with a dozen seed balls each is a wonderful way of spreading the seeds from your refugia garden into the broader world!

Finally, and most importantly, the refugia allows you to do something important in the face of this global crisis and create a true difference. None of us have any idea what the future holds, but as herbalists, we can be here to support and heal the land. Right now, building and maintaining refugia and scattering these seeds outwards could be the single most impactful thing you do to support nature. Fifty or 100 years from now, your efforts might directly lead to the difference between a species that survives or one that dies off—because that’s exactly how refugia work. Even if the broader landscape remains inhospitable, the species are still thriving in that small pocket you created. What a beautiful way to reciprocate with nature, to give back, and to live a life of meaning and purpose.

References

Morelli, T.L.; Millar, C. 2018. Climate Change Refugia. USDA Forest Service Climate Change Resource Center. https://www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/climate-change-refugia

Yunkaporta, T. (2019). Sand talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world. Text Publishing.

Announcements:

The next Land Healer’s Network Call will be on July 7th (note the date change from June 30th) at 2:00-3:30pm EST. More details here!

this is exactly the sort of gardening i’m doing up here, in addition to annual vegetables and fruit trees. since i’m trained as an ecologist, i began by thinking of it in terms of upping biodiversity in my 0.3 acres, just to provide a _seed bank_ for the future. because who the heck knows what might happen. i like the name “refugia”, though. i’m interested in your comment on Paw-Paw though, as i’m north of Syracuse and grew mine from baby sticks, and they’re both doing exceptionally well. also, i’m having issues sourcing Sassafras, as it’s a tap root species? and several local growers didn’t have it. i may actually stop by the Peace Center and see if there are any Haudenosaunee selling or gifting it, since it was a Native advisor to ESF, at a garden talk for HGCNY, who advised people to consider planting it.