We gather to the outstretched rope lines, ready to move the 22-foot-long stone weighing thousands of pounds by hand. Our goal is about a half a mile away, through hilly terrain. This stone is destined for the a place in the ever-expanding Stone Circle at Four Quarters Interfaith Sanctuary. All have gathered for one purpose: to move this massive stone using our hands and hearts, and to give it a home in the honored northern quarter of the circle.

So much preparation has gone into this moment; building this sacred space from the ground up, the years and years of work. Countless hours of developing expertise on how to move stones. More recent preparations, from the “stone peoples intensive” volunteers arriving a week early to prepare the site, building and securing the moving equipment, developing the rituals, and preparing the grounds. And there are the stone movers– the huge group of people who have gathered from far and wide. The evening before, we held ritual around the flame stone and called in our ancestors to bless our sacred work. The next day, we volunteered on one or more of the many paths of service necessary to help the event take shape. Anticipation built, especially for those of us who had never done the work before.

And so, here we stood, on the day of the “long pull.” Our hearts, minds, bodies, and spirits ready for the work ahead. Everyone is quiet on the lines except those who are directing the activity. We stood in silent communion with the stone. The order is given–pull slow and steady. The stone people work closely with the stone, shouting orders, watching to see how it moves along the path, and putting logs underneath so that it can roll along smoothly. The logs are particularly important for rises in elevation and flat areas (as the road we pull the stone down is full of many dips, hills, and turns). The leaders call out commands–we stop, we move left with our ropes, we pull. We stop, shift again to the right, and pull. We gather together to shorten the ropes and pull. We move apart on the longer stretches and pull. We breathe. We pull.

We are many tribes within tribes gathered here to pull this stone. And yet, on these ropes, there are no differences among us. Regardless of race, class, vocation, identity, skill, physical appearance, gender, sexuality, political orientation, or ability, we gather as a single tribe with our one purpose–to pull. We have three lines coming from the stone–I was in the middle line, with my small community of druids surrounding me. These druids are dear friends, people with whom I have long shared sacred space, with whom I’ve conducted the work of initiation, with whom I’ve spent many an evening at the bardic fire, sharing mead, stories, and songs. If I fall, I know they will catch me. But I realize in that moment, looking to the broader tribe of people around me…so would any other person here today. Whatever differences or divisions there were before this stone pull, they fade away, and with that, our small druid tribe flows seamlessly into the greater tribe, all working as one.

Doing the work of raising this stone requires an incredible amount of trust. It requires that we put aside our differences, our disagreements, our pain, whatever we carry with us, and simply trust the other people who are there beside us. You can’t have barriers between you for this work, because you can’t be anywhere but present in the moment. Anything else has no place. I can understand now, in ways that were unfathomable to me before, why the ancients built big things. They built things to build community. They built things to build bonds of friendship and trust that transcend any other boundaries. They built things to bring people together. You couldn’t hold a grudge against your friend or neighbor because the next day, that person you are angry at might be holding the wooden lever that is keeping 2000 pounds of stone from crashing down on you. The ancient monuments that still stand are symbols of that community and trust.

In fact, working in a community to accomplish so many tasks used to be a skill that every human had. Communities worked together to accomplish incredible feats, like building stone circles that stand for 10,000 years. It is no wonder we need our ancestors here to support us–we reach deep within our own blood and reconnect with their wisdom to guide our hands, hearts, and spirits. We are not a separate people, but one. Pull, wait, move. Breathe. Pull. Pull, Pull!

As much as you depend upon your community during the moving of the stone, your community depends upon you. The stone is so heavy; every person is needed. You have to pull your own weight in the most literal way. At one point, we were pulling the stone up a really long hill, and it was really intense. If we stopped, we might not get going again, so we just kept pulling. Our muscles were burning, everyone was sweating, groaning, giving it our all. There’s a temptation at that point to ease up just a little, to not pull quite so hard, to catch your breath. But you don’t. You pull with all of your might because if you don’t, someone else in your community will have to do so, and that might be too much for them as they are already giving their all. This is another form of trust.

If there is one thing that can be said it is that anything worth doing takes time. And stones in particular, move slowly. To move a stone quickly would risk serious injury to either us or the stone. The stone forces us to slow down, to be in the moment, to simply be present, and listen, and attend to exactly what is happening right now. I had to be present in each moment to hear what was coming next. For four hours while we moved that stone, I was in an extended movement meditation where my entire existence was focused on listening for those instructions and doing it exactly as asked. We get into a rhythm. The pauses allow us to reflect on the moment, on the beauty of it. I look to my brothers and sisters of the tribe of the standing people, noting the hickories and white pines who send us their blessings as we slowly pass. As we wait, as we pull, as we move left on our rope lines, as we drink the water that other community members provide, we are simply in that moment.

Our bodies grow sore, but the journey has not yet ended. For some of us, we spend most of our waking hours in our minds, disembodied, our minds focused on screens of information. Our bodies come to life in the moment where we pull, our bodies are fully, and sometimes painfully present, to let us know that we are still alive. Our sore muscles remind us that we are here now, and that we are making this living monument that will last for generations.

As our sled that the stone rested on broke, as our log rollers broke, as everything seemed to break and we moved the stone up the last rise by sheer determination, we continued to pull. Finally, we reach our destination. The stone is once again celebrated and we come together as a tribe. That evening, the warriors, the veterans among us, and others who choose to join, hold vigil over the stone. We let the stone know that the community is here, this day, and always. That evening, we released our fears, doubts, pain, and sorrow and came together as a tribe for the great work, the rising of the stone, to begin.

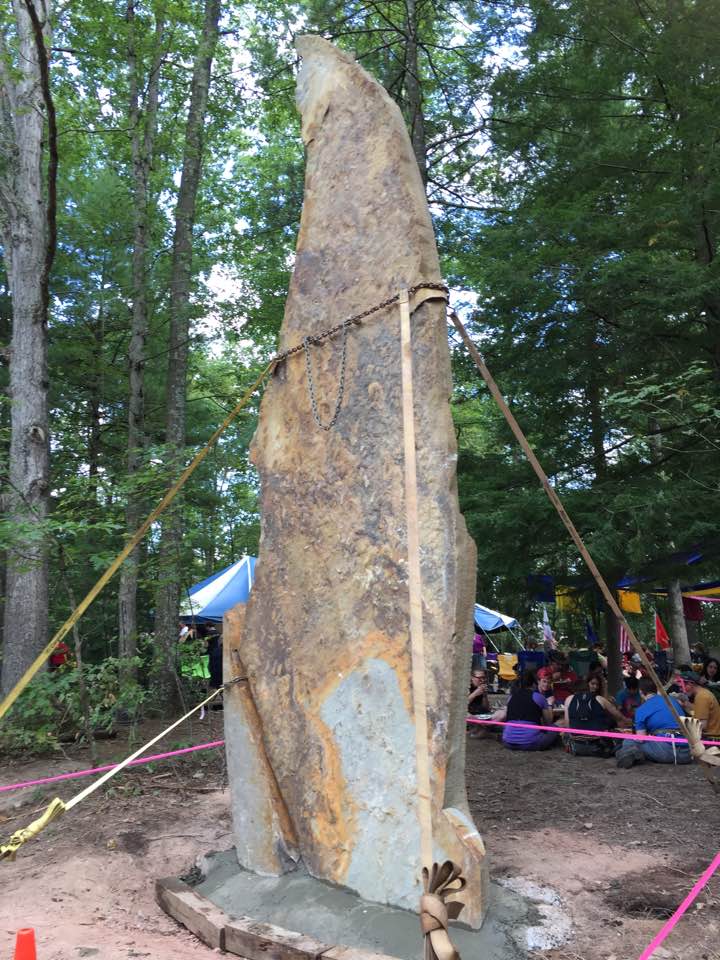

The next morning, it is time for the stone to rise to its sacred place in the north. We gather in the morning. All night long, while the warriors held vigil, the corn mother tribe baked us bread. They offer it to us to break our fast. It is delicious, slathered with honey butter. This warm gift fills our bellies and hearts. We pull, pull, pull and the stone is in place. We watch as the stone people slowly use leverage to lift it up, inches at a time, building sturdy wooden foundations to hold it. We wait, we watch, we listen. Finally, it is time for the stone to rise.

Two ropes are laid out, and those of us who are at Stones Rising for the first time are given the place of honor at the front of the ropes so we can watch the stone rise into place. The drummers beat their steady rhythm, while the entire stone circle is decked out in beautiful colors; an outdoor sanctuary to the living earth. We pull on the ropes, hand over hand, but this is easy work, as we are also using some block and tackle (ropes and pulleys).

Orren Whiddon, whose vision has created Four Quarters, is leading us in raising the stone. He tells us that reason we are using block and tackle is that we don’t have the experience of working in a community together. We don’t have enough control. We would get too excited, and we pull to fast, and so, the block and tackle slow us down. When we are 75% of the way, an additional tool is needed, and it takes time for someone to fetch it from the farmhouse. We hold the ropes. We wait. We breathe. It is not hard work with all of us here; we trust that the community will hold. Then, we are pulling again, hand over hand, as the stone raises up. With a final thump, the stone fits into its hole in the circle. We cheer and hug each other. The great work is done. Children are blessed, the community spends time in celebration, and later, feasting.

The main ritual that evening welcomes to the stone to the circle, it is powerful and moving and magic. I catch my breath and look around at my tribe, their faces shining in the dim firelight. I think about so many things there, as we stand in the firelight as a tribe honoring the new stone. Modern humans almost never have the opportunity to experience something like this. We have grown so dependent on fossil fuels and machines that do this kind of work that we have forgotten the most important lessons of trust, forgiveness, community, slow time, and craft. As Wendel Berry writes in the Unsettling of America, the point isn’t to do something quickly. It is to do it well. This is especially and poignantly true of building sacred spaces. Fossil-fueled powered heavy machinery could never, ever compare to what we experienced here as a tribe. We might gain efficiency in using fossil fuels, but efficiency comes at an extraordinarily high cost. In the case of building a stone circle or other sacred space, it may come at the cost of the heart and soul of a community. Fossil fuels have made life easier, quicker, but certainly not any more full. Fossil fuels have stripped us of an extremely important gift–the ability to work together. Raising this stone has given us the briefest glimpse into the power of what that once looked like. And I want more.

This experience also has a tremendous amount of value to those of us here in the United States practicing nature-based spirituality. As any druid practicing here knows, we are in a bit of a pickle. We are practicing a nature-based spiritual tradition that originated with the Celts–their land isn’t our land. Some, but not all of us, can trace ancestry back to the British Isles in some form or another. That doesn’t really matter much when we don’t live on that soil. The truth is, here in the USA, we live on someone else’s sacred land. That unavoidable fact puts us in a serious bind–the most compassionate, respectful, and meaningful solution is to build our own sacred spaces. I’ve long advocated the necessity of creating our own sacred spaces (and have offered some suggestions for how to do so), and this experience radically affirms and extends this idea. Building small spaces with a few friends, or very magnificent spaces, like the stone circle at Four Quarters, is part of our own flavor of what it means to be an American earth-centered spiritual person, an American Druid, an American anything else.

The truth is, I’ve been attempting to capture in words an experience so sacred, words can never fully describe its power. But for those who do not have such an opportunity to raise a stone, I hope that my attempt to give the experience voice has given you pause for reflection. To understand the work of the stones, you must do the work of the stones. To understand a sacred place, at least the kind we are trying to create here in the USA, you have to take part in the creation of it. Before I raised a stone, I really had no idea what the circle of stones there at Four Quarters meant, and what their power was. I couldn’t hear the singing of the stones. But now, I understand that place. I am connected to it. It is part of me, and I am forever part of it.

And, perhaps, I will pull stone with you next year!

PS: I am indebted to Patricia Robin Woodruff, who took most of the photos in this blog post. You can learn more about her and her amazing artwork here.

What a gorgeous stone! Great to see community working so well together. 🙂

The Flame Stone (as it is called) is certainly one of the most beautiful of stones :).

Beautiful! Thank you so much for sharing! I truly and deeply love Four Quarters. Every since I attended Fires Rising a few years ago, my Spirit feels connected to the land, the stones and to others who call 4QF a Spirit home. I have been very much wanting to attend a Stones Rising for some time now, knowing that it will connect me even more with the land and the stones, but – being a single mom of 2 teens – I am always busy labor day weekend getting them ready for school & preparing for the new routine… alas, but it is so. I am at peace with it, but do long to be there, so thank you so much for your writing & sharing this – so that in some way I can feel connected <3 Peace and Blessings!!!

Katiejoy – it is a difficult weekend for anyone who is involved in schools of any level! (I had my first week of classes right before that). I’m sure someday you will get to come :).

You touched my heart and soul with this one Dana. I have built several large stone circles on my property and feel very connected to them, but to raise a stone……..I hope I can participate next year

Patrick, it would be amazing if you could come! It is Labor day weekend. There are lots of folks traveling from the DC area (including a number of druids) so we can probably arrange a ride if you needed one out to the stones :).

Thank you for your kind words. You have touched upon the very themes that we try to invoke and promote by example. Pilamaye tanka!

Thank you for reading. Blessings of the stones upon you always!

Reblogged this on Rattiesforeverworldpresscom.

[…] O’Driscoll’s blog, The Druid’s Garden , offers another heartfelt take on the work […]