As a species, we are facing a number of challenges that can be overwhelming—from global climate change to failing ecosystems, to mass deforestation and substantial water stress. Many who care deeply about the earth, who see the earth as sacred, finds themselves in a state of perpetual mourning and apparent powerlessness when reading the headlines or seeing destruction firsthand. The sense of being overwhelmed can be stifling, limiting, leaving you unsure as to how to do anything but strongly wanting to do something. It can leave you feeling that nothing that you do is good enough and nothing that you do as an individual matters.

The environmental movement doesn’t really seem to provide a meaningful way response because its largely based on assumptions that mitigate damage rather than actively regenerate. Environmentalism teaches us how to be “less bad” and do “less harm” by changing from plastic to cloth bags, using less energy, or driving a hybrid vs. a gasoline car. Environmentalism teaches us to enshrine forests; to admire them at a distance where we can’t learn about them or effectively caretake them (the importance of traditional caretaking roles for humans in ecosystems is well documented, as explored in Tending the Wild by Kat Anderson). Environmentalism gives us the ethic that “the earth should be protected” while not really teaching us how to engage in that protection. I also think the environmental movement, at least as I have participated in it, is fairly reactive rather than proactive. I think there’s a place for the kinds of work the environmental movement does, and I think they are helpful, but I don’t think they are “enough.”

Sustainability as a concept, I am realizing, is also problematic. (I’ve been using this word myself, but am now transitioning away from it in favor of regeneration for reasons described in this post). Sustainability, which means a “capacity to endure” essentially seeks ways of sustaining what is there. This may mean to sustaining our current lifestyles and levels of consumption (or near similar lifestyles and levels of consumption) while also working to mitigate any further damage to the planet. Yet, the current lifestyle got us into this mess. Why do we want to sustain that? What are we really protecting when we are “sustainable?” Furthermore, it has become another term commonly used by companies to sell their products and services, rather than an ethic or principle for many. I’m not sure of the ethics that fuel sustainability–desire to do less harm? desire to protect and preserve? They are often not very well articulated.

I’ve struggled with both environmentalism and sustainability as meaningful responses because they made me feel like something was missing. Being a better consumer of environmentally friendly goods, or my early attempts at sustainably, still made me feel not so great because I was mitigating problems. I’ve expressed that struggle quite a few times in posts over the years here, and I’m sure that so many of you share it—so the question is, what else is there?

What it seems we really need—as a society and as individuals—are tools for being proactive and directly engaging in long-term regeneration: healing the land, healing the planet, healing ourselves, and rebuilding the sacred relationship between humans and nature. We need tools that go beyond the above approaches and into envisioning “what’s next?” or “what’s better?” So many of the structures of our daily lives don’t work: our homes require too much energy for heating and cooling; our waste is treated as waste; our landfills fill up with things that still have value; fresh water runs from the streets of our cities and into the sewer system; our bodies are pumped with poison and chemicals; and our landscapes are barren and toxic. We need tools that help us facilitate the deep work of healing our damaged lands, to re-evaluate and develop better ways of living, and in directly rectifying the damaged relationship we have with nature. We need an ethical system that is simple to teach and yet profound. We need tools to help us envision the future today–what will our next iteration of lower-to-no fossil fuel living look like? What if we could design for that now? What if we are the ones building what the next iteration of human living could look like?

One set of tools to help us do this is permaculture design. Two Australian designers, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, developed permaculture, or “permanent agriculture” in the height of the sustainable living movements of the 1970’s. Permaculture was developed in response to the growing awareness of the damage humans were causing and the dwindling resources of our planet. Permaculture is a design theory using a whole systems approach modeled in natural patterns; it is a set of ethics and principles that we can use to help us design anything from an outdoor landscape or organic garden to a workplace or a community of people. Millions of people around the world are using permaculture design to revitalize their relationship to the land, enrich their lives, and enhance their communities. To design effectively using permaculture ethics and principles, we must carefully asses, observe, interact, measure, study, and analyze the existing site before we can begin to consider change. The act of interaction, analysis, and observation prior to making change is in itself a powerful tool—it asks us to go from reaction to mindful and directed thought and action.

What makes permaculture different than other things, like environmentalism? For two, permaculture gives a clear ethical system that actually makes a great deal of sense, and that can be directly applied to any design. Permaculture rests upon three primary ethical principles: people care, earth care, and fair share (which I covered in more detail earlier). A goal of any design is to address them all at the same time. We, therefore, design with the understanding that caring for the earth and caring for people are one in the same. Stop and think about that for a minute. The earth’s needs are equal with our own, and both can be satisfied with careful planning and analysis. Furthermore, also a matter of ethics, one of the things permaculture design can do—and do well—is to help us regenerate even the most damaged and poisoned of lands. In fact, many permaculture designers purposely select abused lands as these are the lands that can benefit the most and this is where they can do the most good.

Permaculture can be learned by anyone (most of what you need is freely available online) or through books or courses. Despite its straightforward principles, yet it allows for a lifetime of study and practice. It can be applied to any site or community–from apartment living to rural farmlands. It puts the power into the hands of the individual and the community, rather in the hands of others. It also considers the role of the design in the larger ecosystem and community. Bill Mollison, one of the co-founders of permaculture, described four goals for landscape design: ecological as well as economic; repair and conserve all systems; provide a unique and essential service for the bioregion; and creating something inter-generational (considering current generations as well as future). So while economics is there, for something like the farm; so is repair of land, conservation, and considering the future.

The actual design principles from permaculture are all rooted in nature (and some will be quite familiar to my readers, as I integrate them often into these posts). I have found these principles to be so useful that not only have I integrated them into my life in terms of my living and landscape, but I have used them extensively as themes for meditation and personal growth.

Furthermore, the act of any designing work involves intentionality—something sorely lacking today. Many of permaculture design’s principles used in the natural landscape work to improve existing conditions: keyline design, for example, uses water catchment and keyline “plowing” to quickly build soil, sequester carbon, and effectively manage water. A multitude of techniques unfold from the principles and ethics.

Does permaculture actually work? Yes, it really appears it does! Sites around the world demonstrate just how powerful this approach can be in multiple settings. I’ll share a few examples here from across the spectrum: from large-scale farming to community design to urban settings: permaculture can be applied effectively.

Permaculture’s answer to traditional, large scale farming. Just over 40% of the available land in the USA is used for farming, over 95% using conventional agricultural methods (read: fossil fuels, GMOs, and poisons). Current industrial farming practices emphasize only thing: the amount of food grown for the plate (and hence, the profit of the farmer). The food is grown with absolutely no sense of earth share or fair share, and these practices essentially chemically shut down any natural processes that don’t immediately contribute to the crops and kill the life in the soil. US farms are currently losing topsoil at a rate of 3 cm per year (and topsoil is where life grows; where the nutrients are concentrated).

As a comparison, permaculture thinks about the yields not only to ourselves but also to the land, how farmlands managed differently can also provide: pollen, nectar, and habitat are yields for pollinators, build rather than lose soil, and so on. A farm of this nature would still have plenty of growing capacity for human food production—but it would yield much more. A good example of a larger permaculture farm doing industrial-scale production is Mark Sheppard’s New Forest farm. Not only is Mark regenerating the land and creating soil, habitat, and encouraging biological diversity, he’s out-growing other industrial farms of his size (see his fascinating analysis in Restoration Agriculture). And the yields benefiting people from his farm include honey, wax, propolis, pastured pork, pastured beef, free range chicken, free range turkey, raspberries, blackberries, elderberries, hazelnuts, chestnuts, and more. He shows how perennial treecrops can provide for many of the same caloric needs currently being filled by soy and corn—and they need to only be planted once, as opposed to every year. And, as he writes in his book, he could literally walk away from his farm today and it would still be producing a variety of crops in 1000 years. Now that’s regeneration!

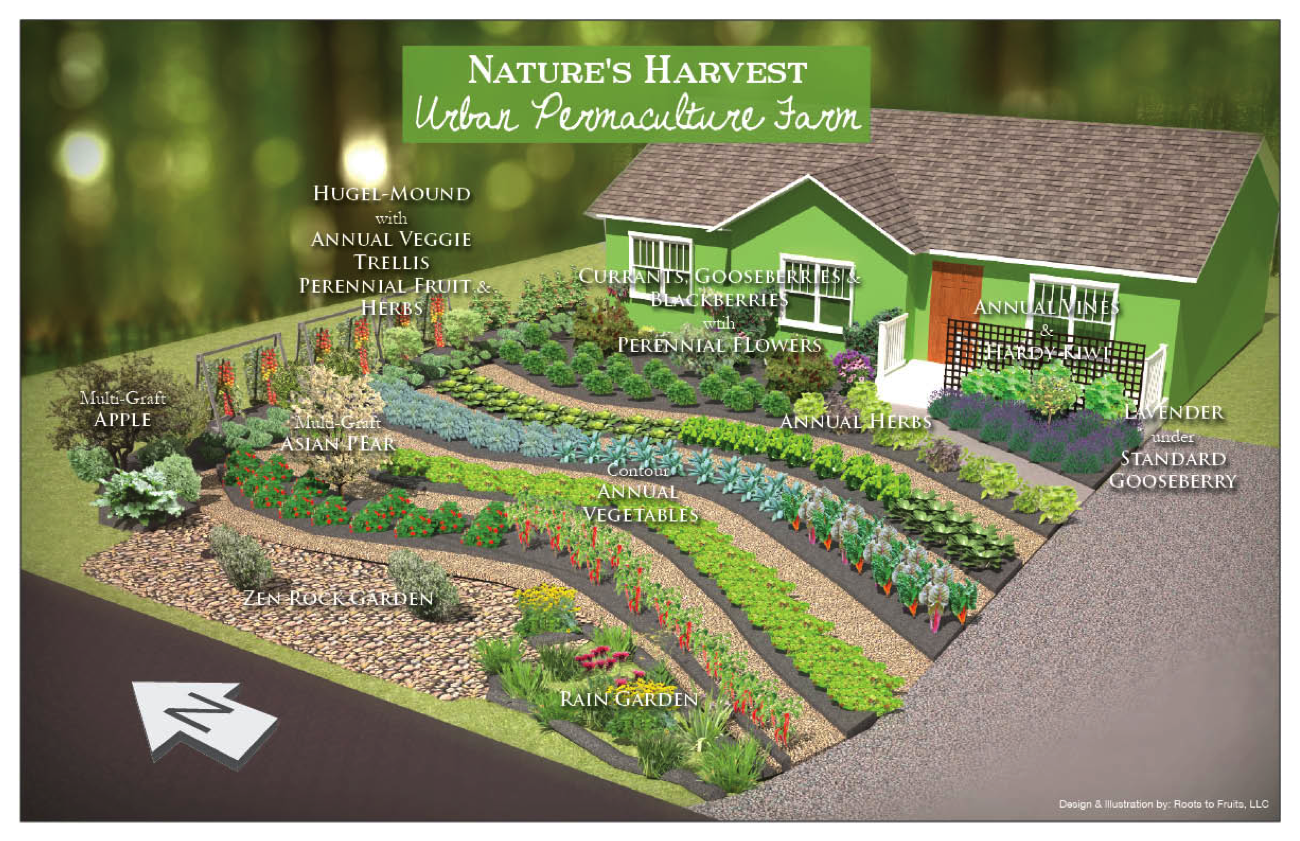

Urban backyard. On the other end of the spectrum from large-scale farming, so many examples exist of urban front and backyard designs using permaculture. One example is Paradise Lot, developed by two permaculture designers, Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates. They regenerated a small urban area and actively worked to sequester carbon. Eric and Jonathan bought a tiny duplex on 1/10th of an acre in an urban setting in Massachusetts. Initially, their site was bare, dry and contaminated. Using regenerative permaculture techniques and soil building, the site is now now extremely abundant and fertile. They managed to sequester over 5 tons of carbon over a period of five years (Imagine if everyone sequestered 5 tons of carbon in their back yard rather than produce more from mowing!). They are producing a variety of yields: food, forage, nectar, good soil, beauty, shade, and more. This was all done using the same principles and ethics of New Forest Farm. Like New Forest Farm, if Eric and Jonathan walked away from Paradise Lot, it would continue to be abundant indefinitely. There are a lot of other sites like Paradise Lot, including one I recently visited as part of my PDC and will be sharing with you in an upcoming post, and my friend Linda’s site in Oxford, MI that I blogged about earlier this year. This is a really empowering and wonderful way to integrate permaculture!

Community-level design. A final example incorporating permaculture principles on a community-wide level was the site of my permaculture design certification course (PDC), Sirius Community near Amherst, Massachusetts. One of the oldest ecovillages in the world, it was modeled after Findhorn in Scotland. Sirius uses permaculture design in every aspect of their living: earth care, people care, and fair share are woven into daily life almost as much as breathing. They mill their own lumber and use it to build structures that are ecologically sound and innovative: greenhouses, a community center, various residences, and more. They use extensive passive solar and heating designs in these structures—when I was at Sirius, several days were 95 degrees, and while it was sweltering outside, it was quite cool in the buildings due to these smart uses of heat and cool (compare this to my townhouse in PA, where anything about 80 degrees inside is completely insufferable). Acres and acres of gardens, including food forests, perennial herbs, and annual vegetables provide a significant amount of the food not only to Sirius’s permanent residents but also to the many guests and visitors (we were fed for two solid weeks from these gardens—a delight!). All waste (including human) is fully incorporated back into the land in some way. Solar, wind, and wood generate much of the power and heating.…I will stop here, as I’m planning a full blog post sharing more about Sirius and detailing more of the incredible things they are doing. But suffice to say, this can be done at a community level, especially from the ground up.

If you are interested in seeing more examples of successful sites, the film Inhabit profiles a number of different permaculture sites across the US and the great work so many are doing.

A ray of hope….

One of the greatest challenges we face in the western world is responding to what is happening globally. A lot choose to ignore it, and go on living as though nothing were happening. Others weep and lament, and feel disempowered to change anything—and so they mourn but do little else. Still others try, but feel that what they are doing can’t make a difference. Even if everyone today started practicing permaculture, we are still paying the hefty tolls of over a century of industrialization and those tolls are irrevocably changing our culture and our world. Yet some of those changes, if we design carefully enough, can be very positive—the problem is the solution, as a permaculture principle suggests.

At this point, as the earth’s atmosphere has just gone over 400 parts per million of carbon, every ton of carbon that we can put back into the ground matters. Imagine if everyone started sequestering carbon as part of their “lawn care” like Paradise Lot! Every response we can have is a response. And its not just individual—when we engage in actions that show a different path, they are like wildfire—spreading further than we can even imagine. I don’t think anyone knows what the future will bring—but permaculture, for me, helps light my way on that path. It gives me tools and ethics of empowerment to teach the next generation. What it does is give me the power of hope.

PS: Look for my post next week, where I show these principles in action on my 5-year homestead project—another success story of a regenerated landscape!

Hey Willowcrow,This is so great!!! It makes me so happy that more people are being exposed to these concepts. My husband and I do riparian restoration, and we are envolved with a group of people who teach about permaculture, land restoration, sustainable grazing techniques and repurposing and using everything. I love everything you said. I would have loved to have been at your class in Mass. It looks like such a wonderful place. I bet everything you ate was grown there. While I can’t say we do everything we would like (stilluse gasoline, flushing toilets- which is so stupid, not growing all our food yet, and stuff), but we do put a lot of time and effort into educating people how to heal their land. Our focus isn’t food per se, as we manage our land as a wildlife refuge, but we do grow some. We have encouraged people around here to use key line, but they haven’t so far, and I see their land blowing away every spring. Our land is green at that time, because we welcome beavers who provide us with sub-irrigation, so we always have deer and elk and all animal people that need water – geese, ducks, etc. We grow grass hay, which the neighbor cuts and uses for his cows, but he cuts it high, so that the ground stays healthy. We sequester a lot of carbon. There is an agency that we work with a lot. It is called The Quivira Coalition. Their motto is The Radical Center. Their mission is to save the land. Ranchers and “enviromentalists” don’t always get along, politically or land use wise. Environmentalists, as you say aren’t doing much (more reactive than proactive) and ranchers are selling off their land to subdivisions because they just can’t make it in an industry that is filled with all the monoculture/animal factory/GMO people, so QC gets these two groups together to save the land. They do a lot of on the ground projects all over the world, using Bill’s (my husband) techniques for water harvesting and other people’s techniques and they also do a conference every year and get people from all over the world to speak about their permaculture and land healing success stories. A lot of organic farmers come. It’s a great conference – usually in November. They set up a room for book sales and sell books from all over about all things permaculture. Many of the speakers have written books, (ike Bill 🙂 ). Bill has developed ways for people to use existing water in benificial ways. To keep creeks healthy, and to keep water on the land longer – treating it as a rescource instead of a nuisance (can you believe anyone would ever think of it as a nuisance? But he helps restore wetlands. Here in NM there are a lot of arroyos that take water swiftly off the land. Usually formed from old wagon roads, or cow trailing. He is able to look at the landscape and see how it was hundreds of years ago, and what it could be like in 20 years. His vision is long term. Anyway, I really ran on here. I guess I just wanted you to know that things are happening around here. We live in northern NM, so it is hard to grow a lot without a whole set up that we plan to do in our retirement (Bill is 80!) I doubt he will ever really retire. He works all over the west and is driven to teach what he knows before he has to leave. I would love to go to a workshop like the one you went to one of these days. I have always loved the concept of Findhorn. I used to read about them in the late 60s, early 70s and had planned to go there, but never have. It would be easier to go to Amherst! Ahhhhhk! I am still rambling! I love what you are doing and teaching, and I got all excited reading it. Wonderful!!! Thank you Willowcrow. It is so exciting that there is hope. Peace,Mary

Date: Fri, 24 Jul 2015 11:32:39 +0000 To: mmaulsby@hotmail.com

Wow Mary, how exciting to hear what you are doing in NM! I’m actually still in my PDC for another week here….and we’ve studied riparian zones, key lines, all that good stuff. I can’t even imagine what the next week will be, but it will be life-changing. What is your husband’s book? Maybe I’ve read it!

I think long-term vision is what we need. Its funny you talk about the river as a nuisance. I wrote about snow some time ago, and I realized that it had the same problem (as do big storms, etc). American lives aren’t wired currently to allow any wiggle room, so when nature does its thing, as it has been doing for hundreds of thousands of years, people respond dramatically because many of them are balancing on an edge time-wise, financially-wise, and so on, and its hard to recover from a small event. We fight nature rather than work *with* nature. The permaculture design certificates are offered all over the world–I’m sure you can find one in NM. Although frankly, I’d come back to Sirius for this PDC again and again. Great people, wonderful community, fantastic instructors…. :). WE have people from all over the world studying here. It is a bit closer to me though!

Oh, lucky you, you are still at that beautiful place with like minded people.

Bill has written several books. The one I was referring to is called “Let the Water Do the Work: Induced Meandering, and Evolving Method for Restoring Incised Channels.” This is about a method he came up with and has been using for about 20 years called Induced Meandering. He has also written a book called “A Good Road Lies Easy on the Land,” which address rural roads, and harvesting water from them. Mostly ranch roads, but some of the oil people are trying to do a better job with roads to the wells. Though of course the wells are horrible, the roads to them cause almost as much damage to the land. He is working on a book right now with another technique for wetland restoration. He is a busy guy – especially for 80, as he is also working in the field and doing workshops as well. Anyway – his name is Bill Zeedyk if you ever want to google him. You are in the east, which is such a different landscape than our here. Have you ever been out west?

I haven’t been out west in a long time, and when I go, its usually for conferences and I’m stuck in a city for four days (blah). Bill sounds like a wonderful man to spend time with!

Well, it is beautiful here. If you come again, we should meet up for luch or something. I will totally make you ditch your meeting and take you to someplace incredible. Haha. Yes, Bill is great. Actually his very first job in his 35 year Forest Service career (from which he retired over 20 years ago) was in the Alleghany National Forest (1957). He was telling me about how the oil people are just decimating it now, as they never had the mineral rights. All those beautiful old black cherry trees. So so sad. Major healing needed. You being there is certainly good for Nature.

[…] also found “The Power of Permaculture: Regenerating Landscapes and Human-Nature Connections,” which […]

Reblogged this on A Vital Recognition and commented:

Reblogging Willowcrow’s wonderfully-worded post with an added strong suggestion to check out the film “Inhabit”, which is linked in the post. The hope-giving documentary shows a wide variety of people, places, and situations that permaculture design has be successfully applied, inspiring the empathetic viewer explore what ways they too could apply permaculture design.

Thank you for the reblog. Let’s hear it for hope!

Hello,

I am a fairly new reader and I really appreciate your posts. What would you suggest for someone who lives in a small town setting and currently feels stuck as an environmentalist? I want to go beyond but have no idea where to find information useful in my situation.

Thank You

Hi Tamara, thanks for writing to me. When you say “stuck” as an environmentalist, I’m not sure what you mean–there are so many ways to interpret that phrase. Stuck as in you don’t feel you are making a difference? Stuck as though you aren’t sure the direction you want to go? Stuck for some other reason? Again, what do you mean by “go beyond”? Give me some more details and we can talk about possibilities! And thank you for posting and for your question!

I got some unique and valuable information from your article. Thankful to you for sharing this article here. What is restoration agriculture?

[…] This big plan wants to make huge, self-sustaining ecosystems. They would copy the earth’s natural patterns and processes. Moving away from old farming and towards new, regenerative ways can help fix issues like less biodiversity, bad soil, and climate change26. […]