As many of us seek to transition from our current destructive culture and create a powerful vision for the future, we need good models of what this kind of transition may look like. As we are moving forward, this often includes a vision where humans can live in harmony with nature, restoring nature, living regeneratively, and learning how to rebuild relationships with nature and each other. But the details of how to do this are often lost. What does it mean to live regeneratively? To rebuild our relationships with ourselves, nature, and others? What kinds of things should we do? How should we live? This past week, I had an opportunity to spend five days at Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage for a Natural Building workshop, and I was so amazed by Dancing Rabbit’s principles, work, and community. I believe Dancing Rabbit offers one such powerful, tangible, and time-tested model of how we can create a more hopeful vision for the future by attending to our living, being, and inhabiting the present. In an age where so many things seem to be going in a direction that harms the living earth and choices often seem limited, Dancing Rabbit offers a future-focused model to inspire generations to come.

About Dancing Rabbit and their Principles

Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage, located in Routledge, Missouri, is an ecovillage that has been around for almost 25 years. Dancing Rabbit has about 50 residents and emphasizes the village in ecovillage, meaning that it is a “community of communities.” It is situated with two other ecovillages with very different kinds of models–Red Earth (which is a homestead-based land trust) and Sandhill (an income-sharing commune). All three–and many other ecovillages–can be found in rural Missouri because Missouri has no building codes or other legal restrictions, which allows a good deal of freedom in how people live, and what they build, thus allowing for much more ecologically-conscious approaches.

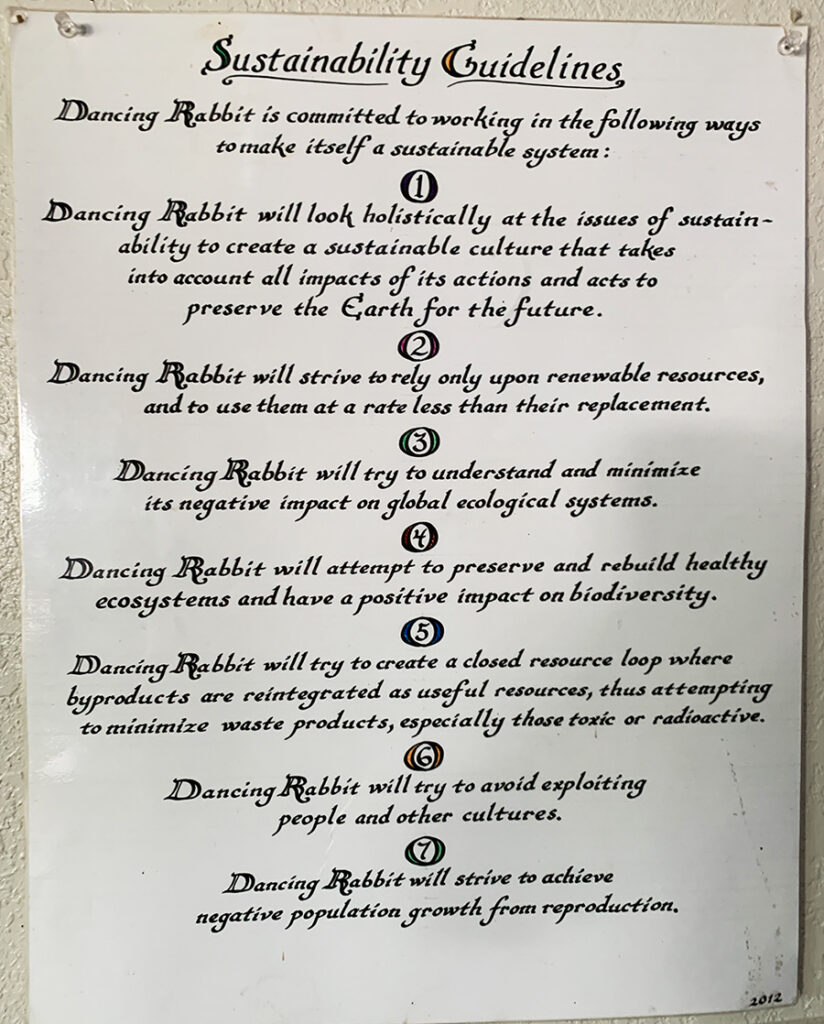

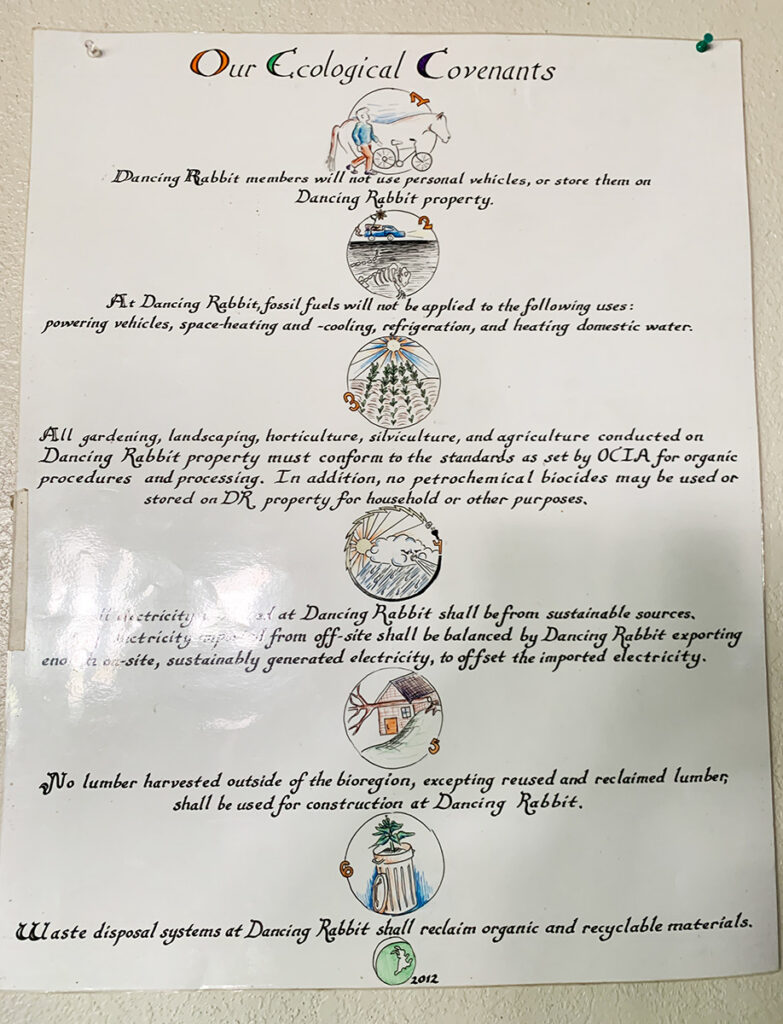

Dancing Rabbit has a strong ecological focus, which is shown by their Sustainability Principles and Ecological Covenants. These guidelines help guide the decisions and everyday living. In fact, they are so important that they are printed and hung right in the common house. I’ll let them speak for themselves:

These principles are enacted in the Dancing Rabbit community in many different ways, including through their village structure, community structure, and engagement with the living earth. Imagine what our world would look like if more communities adopted these principles–these offer a powerful, necessary roadmap for human habitation and interaction with the living earth.

Village and Community Structure

Dancing Rabbit’s model of a village is one that defies easy explanation, and I am going to do my best to describe it as I understood it from my visit there. Each person who joins Dancing Rabbit (after going through both a two-week visitor program and a six-month trial period) joins the village as a resident (called Rabbits). The land that Dancing Rabbit sits on is 280 acres, with the south-eastern corner being dedicated to the village itself. The land is held by a land trust, and so no resident “owns” the land but rather leases the land they live on for a nominal fee each month. Houses and other structures built on the land can be bought and sold, and only residents can buy, sell, or build new homes or other structures. The average lot is about 2500 square feet, which is enough for a small house, garden, and shed; residents can also lease more land further out from the village for various agricultural pursuits. Dancing Rabbit has a Dairy share (goats, cows), several gardens tended by subcommunities, an orchard, and many small residential gardens. The term that I heard over and over again is that it is a “community of communities” with a lot of freedom, flexibility, and the ability to adapt. I’ll share some of the core features of Dancing Rabbit to show how they enact this ecological approach. This page offers an overview of their impacts compared to average Americans–Rabbits, in general, consume about 10% of what an average American would consume in terms of fossil fuel, water, and more.

Vehicles. Recognizing the destructive power of fossil fuels, Dancing Rabbit members agree to not use personal vehicles or store them on Dancing Rabbit property. Dancing Rabbit residents instead can make use of a fleet of fuel-efficient vehicles or the community’s pickup truck on a per-mile basis. Since they live in a very rural area, the vehicles are often used to make trips into town, pick up materials for buildings or gardens, or help transport guests from the airport or train station nearby. Thus, Dancing Rabbit has reduced the “personal care” which could be held by up to 50 people to just 5 vehicles and also significantly reduces the cost of having access to a vehicle.

Energy. Many people also choose to join the village’s energy co-op, which is their own energy grid, produced sustainably through a bank of solar panels. Other Rabbits choose to generate their own power with their own solar panels (most commonly), windmills, and batteries. All Rabbits commit to using wood for heating and ecological design for cooling.

Accessibility. In some ecovillage models, you have to make a sizable financial investment to “buy in” which prohibits many from joining. At Dancing Rabbit, anyone regardless of income can join because there are many inroads in. Residents have many different options to choose from: tenting, renting a room in a house, work trading, building their own low-cost naturally built home, or buying a home that already exists on the property. These options are further detailed on their website, along with associated common costs. They work very hard to keep costs low, which allows more diverse individuals to enter and join the village–see more about this under “houses and habitats” below.

Meal sharing. A final thing that the Rabbits also share is a community approach to meals. At present, there are three different cooking co-ops. Many of them also have community-tended gardens, animals, or other shared resources. If you join one of these, you get to eat your meals each night with your co-op, and all co-op members take turns cooking (imagine a situation where you only had to cook once a week! Amazing).

Decision making. Consensus-based decision-making and non-violent communication are cornerstones of how the community addresses challenges, resolves conflict and creates a future together.

While I’m describing the community structure in broad strokes, I think it starts to be apparent how Dancing Rabbit is able to live up to their ecological covenants and sustainability principles–by re-thinking the idea of how a community is organized, by sharing resources, and by learning and growing together.

Houses, Habitats, and Land

A big part of creating an ecologically-conscious lifestyle involves the places we inhabit. And homes and structures are the basis for so much that Dancing Rabbit accomplishes–how else could you avoid using fossil fuels for heating, cooling, and refrigeration? Intelligently designed houses, using natural materials, on land that is not restricted by building codes, seem to make the perfect mix. I’ll only briefly share about the homes at Dancing Rabbit because I’ll be doing a follow-up post that offers more details of this about my natural building workshop and will go into more detail.

I’ve visited other ecovillages in other places in the country, and those that are located in areas with more restrictive codes routinely say that the growth of their village is restricted by those codes. For example, one ecovillage I visited required electricity (grid-tied), running water, and septic tanks for every single structure–and because of that, they were perpetually short on housing. Their village couldn’t grow because every house they built cost them almost $30,000 in these hookups and systems. Fortunately, the lack of codes in rural Missouri basically means that Dancing Rabbit can build whatever structures they like, where they like, and of whatever size they like–and they have many, many naturally built structures. This also means that ecological living really can be taken to a new level at Dancing Rabbit. Another thing about Dancing Rabbit homes is that they work intelligently with the living landscape–passive solar is a common feature, as are homes that are partially underground or feature other natural heating and cooling methods. I got to stay in a great little earthbag “gnome dome” while I was there which was warm in the evenings (dipping into the low 50’s) and cool during the days (rising to the high 80’s) just by design.

Another aspect of the community that is critical is the creation of common areas. Without restrictive codes, not every building needs everything, and thus, a lot of resources can be shared. The Common House is a large structure centrally located in the village that has showers, composting toilets, internet, a washer and dryer, a library, private workroom, offices, community space, an open kitchen, refrigerator, and play areas. In other words, you can walk to the common house to get nearly all of your needs met–get a hot shower, cook some food, get online, wash your laundry, and so on. Because the common house is centrally located, this allows people to build houses that are much simpler–they don’t need their own electricity, plumbing, bathrooms, internet, and so forth if they don’t want–allowing much more ecological choices. Community members pay a small fee to use the common house and also offer labor in various ways to support the common house (e.g. anyone who is using the composting toilets is involved in helping move the humanure to the compost areas). When we were visiting, in addition to the common house, we got to tour Sub Hub, which was a second, smaller common house that two community members were building–as the community expands, so does the need for more common areas. The whole community house is a really, really brilliant system that is adaptable, flexible, and really speaks to how to live in a way that is sustainable.

Naturally built homes are extremely energy-efficient, use local/reclaimed materials, often use either light clay straw or strawbale for insulation, and are wood-heated. Most of the homes are cozy but not huge–they don’t need to be huge if you have access to community spaces that handle a lot of basic needs. Residents often build their own homes and/or buy a home that is already built; the built homes can be customized in any way imaginable, and often feature art and other wonderful aspects that allow for much more uniqueness and expression than the common modern home. Members can have very simple tiny houses or more elaborate houses with water collection, electricity, internet, a kitchen and/or bathroom. Or, they can create a very small structure that is private and cheap, with none of those features, and then just walk to a common area to access everything. These are the homes of the future–with very low physical and ecological footprints and the ability to be built and maintained by hand.

A final feature I wanted to talk about with the land is land use. The village itself features an array of gardens, walking paths, and wonderful nooks and crannies for you to get lost in. As you move to the edges of the village, you see barns, livestock, larger gardens, orchards, and other features. Further out, you can see forests as well as some of Dancing Rabbit’s land regeneration practices where they have planted thousands of trees to help heal the damage of long-ago farming. Because of their principles and covenants, it is quiet because people aren’t constantly burning fossil fuels for lawn mowers, power tools, chainsaws, or vehicles. With codes or restrictive laws, there is also a lot more flexibility about things like lawns. The village mows paths, and some people use a sickle, an electric mower, or a hand-powered mower to keep small lawn areas clipped for gathering, but most of the village chooses to grow gardens rather than lawns. The path system is all walkable, meaning that you aren’t constantly healing the drum of fossil fuel-powered machines.

Reflections

I think that a lot of us–myself included–spend a lot of time negotiating between earth-honoring, ecologically-based living and still maintaining a foot in the present age to pay for our sustainable living practices (e.g. bills and mortgages). That difficult balance often has us feeling pushed and pulled in various directions, and we are viewed as oddities or extreme by modern society. We are feeling constantly like we are swimming upstream, doing what we can but never feeling like we are doing enough. I think that going to Dancing Rabbit was like coming home–to a place where my lifestyle was reflected in every decision and choice that was made, starting from the ground up. They modeled for me how much further I have to go. But they also reinforced that there are real limits to sustainable living outside of this kind of setting, particularly surrounding things like building codes, restrictive laws about mowing your lawn, and so on. Dancing Rabbit is located in one of the least restrictive states, and it could not be replicated in many places (such as where I live in Pennsylvania). This has given me a lot of food for thought–how do we change the systems that restrict many sustainable living activities so that more of these kinds of places can be created?

I also was struck by the peace in the village. It felt right in ways that were hard to describe. I think one of those ways is that in most places where humans are (including where I live in a very rural setting), you are constantly hearing the drone of more than one power tool, lawnmower, or chainsaw. It’s like there’s always that buzz in the background, disrupting your thinking and the general ambiance. This is part of why I have focused on doing a lot of my meditations and interaction in nature on rainy days–usually, there is less fossil fuel noise pollution. At Dancing Rabbit, the psychological difference and lack of these constant machines are palatable. There’s also a lot less technology on average–they are using plenty of appropriate technology, but people are spending more time talking to each other rather than having their heads buried in their phones. There are also a lot fewer wireless signals in the air, broadcasting everywhere. The cultural norms towards technology were different and healthier. All of these things–along with many others–really sang to my spirit. I slept better in my little Gnome Dome (earthbag home) than I feel like I slept anywhere–and a lot of it had to do with waking up to the sounds of roosters crowing and birds singing, rather than my neighbor’s obnoxious lawn mower.

Another takeaway I had from being at Dancing Rabbit is the resilient and groundbreaking work that the Rabbits are doing. I have a tremendous amount of respect for individuals who have made this wonderful village their home. I heard story after story of how they made the choice to leave their careers and live by their principles. The work they are doing is incredibly important and their model gives me hope. Their pioneering spirit, education, outreach, and more are a welcome balm in this challenging age.

In sum, Dancing Rabbit’s pioneering spirit, smartly designed community, and vision for the future is a welcome balm in such a challenging time. I would encourage all of my readers who are able to go and visit this amazing place–take their workshops, learn from them, and see a real model for a sustainable future that is comfortable, attainable, and just. I know that I will be visiting Dancing Rabbit again in the years to come to be inspired, learn, and grow.

How are relations with the neighbors? Are the Rabbits a self-contained oasis among other self-contained residences, or is there an interaction and larger sense community in the area? Thanks for your thoughtful writing.

Hi Dan,

Its quite a rural area with a lot of space in between everyone, which certainly helps. I don’t know about all of the neighbors, but I didn’t hear that there were problems. There are two other eco villages right in the same area. You can walk to Red Earth (I’ll do a post about them as well sometime soon); so there’s a lot of interaction between those communities. I got to meet a few of the Red Earth homesteaders and we also toured some of their homesteads and naturally built homes. So I think there’s a pretty nice sense of community there–and Missouri is apparently a mecca for eco villages because of the lax laws, so there’s also others in the region.

To be clear, there ARE building codes for the State of Missouri…but the local counties don’t have the money or the resources to enforce them, so we have a fair bit of leeway. We DO need to conform to state DNR (Department of Natural Resources) regulations for greywater systems due to our local population density. However with universal adoption of an engineered humanure system, we have very little outflow.

As far as neighborly relations go…some of our kids go to public school, some of us go to one church or another, some of us play bridge on a weekly basis with other locals, and we dress modestly when we visit the local Mennonite businesses. We publish a regular column in the local newspaper talking about what’s been happening in our ecovillage. One of our members is the local fire chief. We interact with the wider local community on a regular basis, and are not seen as *that* weird. Aside from bridge club, some locals come to Dancing Rabbit to see one or more of our health practitioners (acupuncture, massage therapist, etc.).

We’re certainly not a utopia, and don’t pretend to be. We’re just trying to figure out how to live in better alignment with our values and with each other, and share what we learn so that others can move in that direction also…wherever they are!

Hi Cob, thanks so much for your comments and clarification! I appreciate your thoughts and sharing. Thanks again for the great time at Dancing Rabbit :).

Actually Cob, building codes are enforced on the county level and there are no building codes for our county. Some counties use generic building codes such as the IBC, International Building Code, while others make their own elaborate code.