The wheel of the year is a principle that many in the druid traditions think about in terms of seasonal celebrations. The wheel is different for people living in different ecosystems, and one of the things you can do is develop your own localized wheel of the year, which can help you understand your own seasons, how to observe and honor those seasons, and also reflect those seasons in your own life. This is one of the first ways that many people go from being disconnected from nature to feeling like they belong to their ecosystem–by simply observing how the seasons change around them and taking part in various seasonal harvests, festivals, and activities. The wheel of the year is also an opportunity for us to practice these same cycles in our own lives, including creating times of abundance and times of fallow. In my own life as an herbalist, wild food forager, and homesteader, I see these wheels of the season woven through almost everything I do. The seasons and weather determine everything: from when we plant garlic to when we harvest tomatoes, and living closely by the wheel puts me in a deep relationship with the world.

I’ve written a number of posts in this area including offering free wheel tools for mapping out your own wheels, wildcrafting your wheel of the year part I and part II, and creating observances and activities for your local wheel, . But in today’s world, the wheel of the year is also being impacted by the age of the Anthropocene, so I’ve written a series on that as well, exploring new themes for each of the traditional eight druid holidays. In today’s post, I want to delve into a specific aspect of the wheel of the year tied to herbalism and wild food foraging practice–harvesting and reciprocal practices by the wheel of the year.

Wild Harvesting and Reciprocation by the Seasons

Few things can teach you as much about the wheel of the year as taking up a wild food or wild medicine practice and developing a reciprocal practice with the land. I pair harvesting and reciprocation together because one, they belong together, in that we should always give more than we take. But also, in order to offer a full reciprocal interaction with the land, sometimes you are harvesting and reciprocating at different times of the year.

For those that are new to these ideas, I created this guide with graphics that you can use and share. I also have two posts introducing you to the ins and outs of foraging practices if you are new and just getting started. I recommend that everyone learn a little bit about foraging and reciprocation as it allows us to deepen our understanding of our own ecosystem’s wheel of the year, embed ourselves deeply in our landscape, learn what is abundant and what needs to be protected and learn how to connect with nature to both support our own needs and to give back. The wheel of harvesting allows us to follow the sources of wild food, wild medicine, and reciprocal practices to honor and give back to the land. It also allows us to observe the changing climate in the age of the Anthropocene.

When I first got into wild food and wild medicine harvesting, I was amazed at how quickly the land changed–how the harvest window of some plants and mushrooms were quite brief, how they varied based on rain, temperature, and other broader climate factors, and how quickly I could miss the opportune moment. Foraging taught me that I had to really be deeply embedded and observant in the world around me. Foraging also taught me relationships with plants–I often couldn’t do much for a plant in terms of reciprocation (beyond asking permission and making an offering) in the moment, but later when the plant went to seed, I could come back, scatter and plant the seeds, and continue that wheel of the year.

For example, I’m friends with a large milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) patch in a local clearing in the forest near where I live. I’ve been visiting this patch for almost 10 years. It is a beautiful place with thousands of milkweed plants, more than enough for me to harvest a bit for fresh eating in the summer–and milkweed is one of my favorite wild edibles! But I always return to the patch in September and October to harvest the seeds–there is no need to scatter more milkweed in the abundant patch, so I carry them in pouches and spread them in other places as the fall turns to winter. In this way, I am both harvesting some milkweed for my own use and also being able to spread the seeds of my friends far and wide, repopulating a key species that has been in decline. These two activities happen at different times of the year, based on the yearly cycle of the milkweed. In this way, I am both harvesting some food for myself and my family but also ensuring that the plant species survives by spreading the seeds of these plants that offer me food. This is what I mean by reciprocation.

Reciprocation looks different based on different plants. My reciprocal and honoring interaction of the multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) involves harvesting literally as much as I can of her for wild medicine–tea and tinctures–because she is opportunistic and is too abundant and is harming other plant populations. In this case, I might harvest the hips and then also cut the plants and pull out the roots, to minimize her disturbance. That helps the overall ecosystem, and while Multiflora may demand a blood offering for this work (by scratching me with her thorns), the larger spirits of the land tell me this is the right approach.

Harvesting by the Wheel of the Year – General Principles

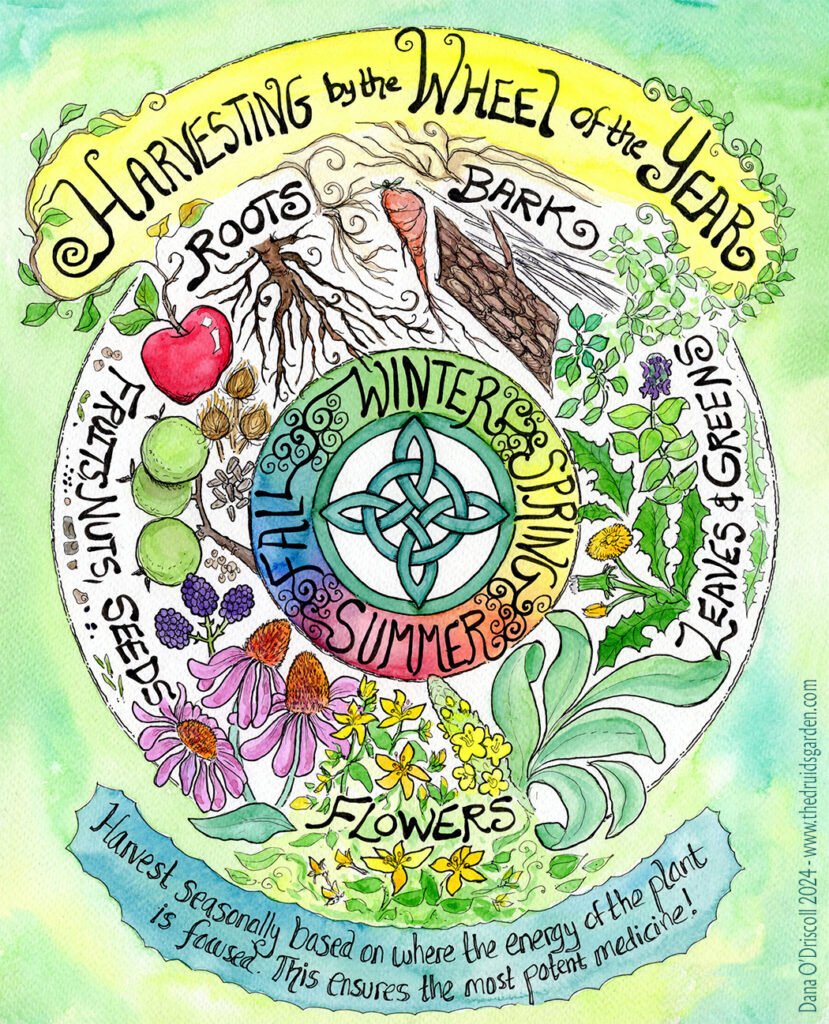

The graphic above I’ve created shows the general pattern for harvesting by the wheel of the year if you live in temperate climates where you have four seasons. Since I live in one of these climates in Western PA, and have always lived in a temperate climate, I can’t speak about other climates but I would encourage you to use the resources and posts I linked above to start figuring out what the wheel of the seasons looks like where you live.

The general principle is that you want to harvest seasonally based on where the energy of the plant is focused.

In a temperate climate, in the spring, the plants are either coming up from scattered seeds or they are returning from their slumber, where their nourishing roots kept them alive in the cold winter months. Thus, the spring focuses on greens and leaves. As those plants grow and strengthen into summer, the energy of the plant moves to flowers, which we see in my bioregion especially starting in mid-May with the Dandelion and moving into the Summer solstice and beyond. As the flowers complete their life cycle, they turn to fruits, nuts and seeds as we move from summer to fall. These fruits, nuts, and seeds work to spread the genetic material of the plant to new locations–and as part of our reciprocal practice with wild foods and medicines, we can do this work too. As the plants begin to die back after their life cycle is complete, perennials put their energy in their roots so that they can again survive the winter. As we go deeper into the winter, this is a good time to harvest both roots and barks, when the plants are in dormancy. As spring returns, the cycle begins again with new green growth.

Let’s consider our friend the common mullein (Verbascum thapsus) plant as an example here to illustrate the wheel, reciprocation, and harvesting by the wheel of the year and also some of its complexities. Mullein is a biennial, meaning that the first year the mullen grows as a basal rosette, creating a beautiful fuzzy circle of big pale green leaves. The roots store energy through the first winter and then the second season, the stalk shoots up a beautiful huge spike full of flowers and later seeds. At this point, the life cycle of the plant is complete and the seeds scatter to create new mullein plants. Understanding this specific life cycle and the wheel of the year is critical for both harvesting and reciprocation, especially since Mullein has several different medicines present in the flowers, leaves, and roots. Mullein leaves are a wonderful exportant, helping remove lung congestion and encouraging a productive cough that can get up phlegm and clear the lungs–both in tincture and smoke. They help clear the airways and are mildly demulcent and astringent. They can be harvested throughout the growing season but I like to harvest them before the flowers come in (or in a 1st year mullein plant that will not send up a stalk, I can harvest them throughout the growing season). Mullein flowers are wonderful analgesics (pain relievers) and have demulcent, nervine, sedative, and anti-inflammatory properties. They are well worth seeking out but may only be in season a few weeks–they must be harvested a few at a time from each stalk, with you coming back every day or so to harvest more. Mullein roots, from the first-year plants, are anti-inflammatory, anti-spasmodic, diuretic and nervine, and are often used for strengthening the bladder’s trigone muscle when there is leakage (combined with other plants, like corn silk or nettle root!). They can really only be harvested at the end of the first season (or in a pinch, at the beginning of the 2nd season). As I recently shared in my mullein torch article, you can also use the mullein stalk to make mullein beeswax torches after she’s died back for the year–and that stalk is also what you would gather to scatter the seeds for more mullein in a reciprocal practice.

So knowing both what I wanted to harvest from the plant for medicine and understanding this wheel of the year sequence can help set me up for success. Without it, I might have no idea when to go get the flowers (or how to find them) or when would be best for the leaves.

Another observation here is that the growing season does happen so quickly–you need to be on top of things. This is especially true in an age of climate change–what used to be traditinally blooming at the summer solstice may now bloom several weeks earlier. In fact, this entire season was off by about 3 weeks–everything blooming about 3 weeks earlier than what it would normally have been. So you also have to observe if a warmer or cooler or wetter spring may impact the overall season and when you can harvest for either food/medicine or for reciprocation.

I don’t have mushrooms on this list. I would need to make a separate graphic for mushrooms, as rather than having that same kind of seasonal cycle, they often have seasons when they can be found. There are spring mushrooms, summer mushrooms, fall mushrooms, and even winter mushrooms. Some mushrooms like tinder hoof fungus (Fomes fomentarius), Chaga (Inonotus obliquus), or Artist Conk (Ganoderma appalantum) grow over many seasons, but The majority of the mushrooms have their own time they fruit in the wheel of the year. Usually, they are other markers to give you a hint of when these mushrooms may come out. However, with increasing heat and drought, it is more tricky than it used to be. This is where looking at larger patterns, regular observation, and regular interaction can help!

New Book Project and New Online Mushroom Herbalism Course Announced

I have two things to share. One of them is that I’ve started working on a herbalism coloring book and a fully illustrated guide to herbalism book. I don’t have the name for the project, and the graphics shared in this post represent one of the pages from the book. I’m planning on working on this in the next year or two, and you’ll get bits and pieces shared here and on my Instagram account. I want to create something entirely by hand, in honor of books from the 1970’s like Alisha Bay Laurel’s Living on the Earth and inspired also by the early Americana work of Eric Sloane. This is to embrace the humanity of it all as a statement against the astounding amount of bad AI-generated content (writing and art) out there today. So hey, I can guarantee you that 100% by hand created book = 100% by a human being. If there’s anything you’d like me to see, please share!

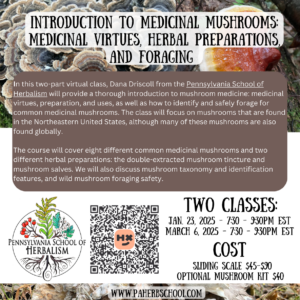

The other thing I’m happy to share is that through the Pennsylvania School of Herbalism, I’m offering a fully online two-part mushroom medicine class that takes place in late January (session 1) and early March (session 2) It has a sliding scale options to make it affordable to anyone. As you know, I’ve been studying mushrooms and herbalism intensively for many years and am ready to share and teach! I’ve taught a shorter version of this in person over the years, including last year for our Western PA Mushroom club. We’ve also teamed up with a local mushroom farm to offer a medicinal mushroom kit you can buy for the two preparations covered in the course if you live in the US. Please click here to learn more about the upcoming mushroom course or see the flyer below!

Oh I’ll definitely be keeping an eye out for the new book! That sounds like it’d be so fun to color and learn at the same time

Awesome! Now I just need a year or two to finish it :).

The devastation of Hurricane Helene upon the land , trees and rivers of Tennessee and North Carolina is beyond comprehension. Are there any groups focused on healing in the area? I have reached out to my local tribal council in Northern California for instruction on the making of “Bokashi Balls” used in river clean up. What are others doing?

Hi Janeen,

I don’t know of any groups focused specifically on healing the area, but we could get a group together to help you through the Land Healer’s Network. We can setup a ritual time and have different people around the globe direct energy, if that would be of help. Please let me know!

I’m writing from California. The movement does not require me personally. I thought land and river healing would be on the hearts of others. If you feel called to organize others; that would be amazing.

Hi Janeen, I’d argue that the movement needs every one of us personally–including you! I am already organizing others – please see https://aoda.org/earthrituals/.

AODA does yearly rituals to bless the land, sea, and sky and also our community. These are large-scale and distributed rituals.

Hello Dana. Thank you for all the wonderful thought provoking posts you write! My question on this one – I have thought about the year as a circle for decades, but in my mind, it always went counter clockwise! Do you know a reason for that? or am I just thinking backwards? 🙂

Hi Linda,

That’s a great question. I’m not sure that I’m the best person to answer it as I am dyslexic, and the order of things or the direction of anything A) never makes any sense to me and B) often gets mixed up, lol!

But here’s the way I always thought of it. If I were standing in the south, looking north, staring at either the north star or the great bear of the starry heavens, I would see the sun rising in the east. The sun would go overhead and then go set in the west, and I’d see the moon rise. So I think the elements, tied to the directions, is tied to that idea.

Blessings,

Dana