Learning and connecting with nature is a big part of practicing any kind of nature-based spirituality. As we know in the druid tradition, a multitude of ways exists to connect to nature. In order to connect with nature on a deep level, we need to understand nature, build nature knowledge, and use that knowledge in the world around us. There are lots of ways to know nature–spend time, observe, interact, use parts of nature in your daily practice, learn how to use nature to meet your own needs, and so forth. Knowing nature takes many different forms, and all of them are useful and relevant as we build our knowledge and understanding of the living earth. In today’s post, I’m going to share how to get to know nature better through bardic arts explorations. While I’ll use my own journey in botanical art and illustration as an example, the principles in the post surrounding observation can apply to anyone who is seeking to connect with nature through a creative, artistic practice (visual art, music, writing, etc).

One of the critical skills of deepening awareness with nature is observation. We teach this in AODA. In AODA, we ask members to go out into nature each week and observe the world around them, focusing on both the microcosm (the petals unfurling from a single leaf) and the macrocosm (the field of flowers). We ask people to engage in nature in multiple ways, including through stillness and focus. You can learn a lot just by slowing down and interacting–and taking the time to do this is always time well spent.

One of the critical skills of deepening awareness with nature is observation. We teach this in AODA. In AODA, we ask members to go out into nature each week and observe the world around them, focusing on both the microcosm (the petals unfurling from a single leaf) and the macrocosm (the field of flowers). We ask people to engage in nature in multiple ways, including through stillness and focus. You can learn a lot just by slowing down and interacting–and taking the time to do this is always time well spent.

However, it can be challenging to take up a practice of nature connection through this kind of practice for several reasons. The first is that, at least for a lot of people in Western cultures, nature and activity go hand in hand. When most people are out in nature they are moving–going for a hike, backpacking trip, kayaking, or walking/running. Some people are particularly committed in these outdoor activities to making certain amounts of miles, and may not always take the time to be in quiet and stillness. The second issue is that we have cultural and technological challenges with observation and paying attention. As technology becomes more ubiquitous, research shows that technology is training our brains to be less focused and more scattered, and mounting evidence is demonstrating that tools like smartphones are decreasing a range of cognitive functioning including our ability to pay attention, remember, think, and even regulate our emotions. I shared about this extensively in my recent posts on ditching the screen and embracing the green! Thus, the technologies that we use every day make it harder than ever before to simply sit still and observe nature.

And yet, observation of nature is a very powerful tool to deepen your connection with nature. By deeply observing, we can understand how things form relationships, we can explore how the wheel of the seasons unfolds upon the landscape, and we can learn about nature in more robust ways. We can understand the mysteries of nature. These are the mysteries that our ancient ancestors unlocked: of the planets and movement of the heavens, of the stones, of the trees, of the uses of woods and plants–so many things. This is knowledge that may be lost, and we can bring it back.

I suggest that anyone who is taking up a nature-based spiritual practice spend time observing and building their observation skills. In previous posts, I shared other techniques for this work: the druid’s anchor spot and the tree for a year challenge: these are rooted approaches to observation and interaction where you choose a spot to spend time in at least several times a week, or you choose a tree to visit each day for a year. These are ovate-based approaches, focusing on your relationship to the living earth and building nature knowledge through direct interaction. But these kinds of “sit still” practices may be difficult for some to do. So today, I wanted to share a third technique rooted in the bardic realm: using our observational skills to carefully create renditions of the natural world through our creative practices. And through all of this, it allows us to open up new experiences, connections, and deepen our relationship to other beings. So now I’ll delve into Drawing, Botanical Illustration, and share a few examples, then I’ll zoom out and discuss some general principles that can help you apply these ideas in a wide range of creative disciplines.

Drawing in Science and Botanical Art

Drawing is used both in artistic disciplines as well as scientific ones to help us learn about nature on a much deeper level. I have found it a particularly good way to really get to know plants, trees, and my local ecosystem and to slow dow. By spending time in close observation with a goal of replicating parts of nature, I end up looking closer, observing minute details about my chosen subject, and building a much more intimate connection.

Within the realm of science, we have a wide range of inspiring figures who used drawing to deeply connect and learn from the world around them. From Beatrix Potter to Charles Darwin, drawing is more than just one way of reproducing the world around us, it is literally a way that we can deepen our understanding. In the link I just included to Charles Darwin, this article shares how his drawings of the natural world helped him come to propose his theory of evolution–which he eventually shared in On the Origin of Species. Drawing is used in many scientific fields as a core skill to learn, reason, and think through problems.

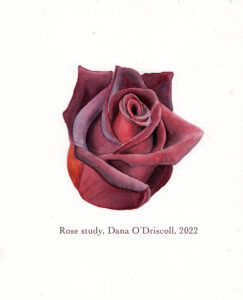

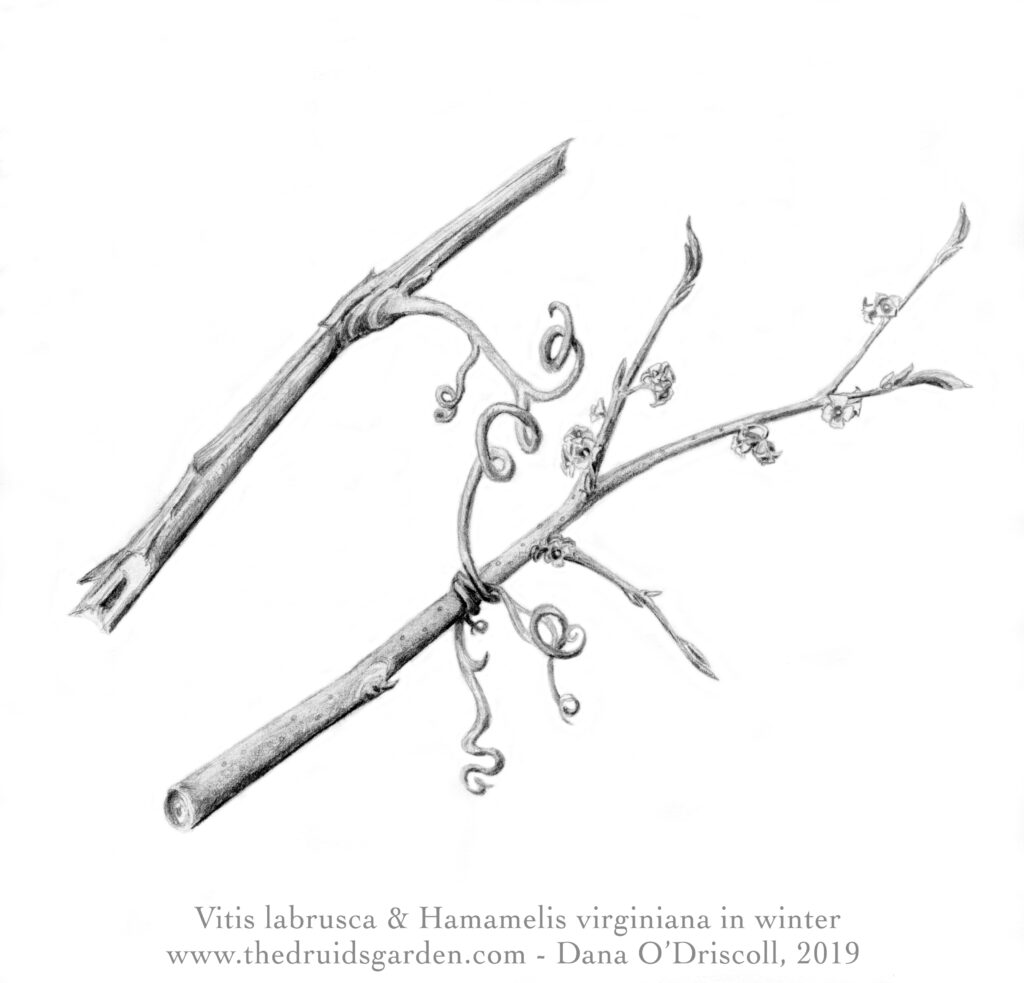

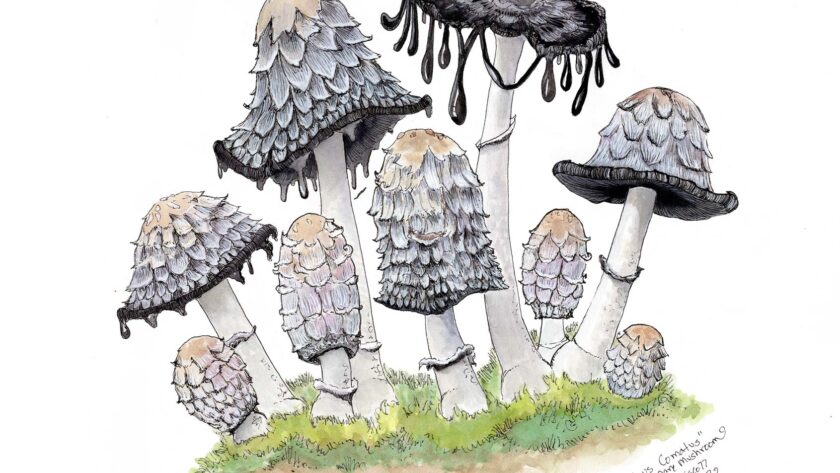

On the more creative side, one of the disciplines that I have been learning over the last five years is Botanical Art and Illustration. To study this, I’ve been enrolled in the Phipps Conservatory Botanical Art and Illustration Certificate program in Pittsburgh, PA–I will be finishing up my certificate in early 2025. Botanical Illustration is the hybrid of fine art and botany; we work to hone artistic techniques and media (traditionally pen and ink, graphite, watercolor and/or colored pencil) that allow us to render plants, flowers, mushrooms, trees, insects, and more with scientific accuracy. Botanical art seeks to capture, as accurately as possible, minute details about plants and other flora, rendering them in a way that allows clear identification and scientific accuracy–someone should be able to identify a plant or species in the wild from the drawings that an artist produces. In the process of pursuing this very rigorous and technical discipline and spending many hundreds of hours in observation, I’ve come to some interesting conclusions that I wanted to share. I don’t know how many druid botanical artists there are out there, so maybe these observations will be useful to others dedicated to their bardic arts!

Bardic Arts as Gateways to Deep Connection – Drawing and Botanical Art

I want to share two stories to understand the magic of drawing as an observation–after I describe these stories, we’ll talk about some general principles if you want to use observational practices in your own bardic arts.

In one of my early botanical illustration classes, I really started to get clued into how special this particular art form was not only as a bard but also as an ovate. For my final project in one of my first drawing courses in 2019, it was already December and there wasn’t much out there to draw–but I was drawn to the witch hazel who had recently finished blooming. I thought I knew witch hazel. I had spent literally hours with her sitting in a witch hazel grove, I had depicted her as part of the Plant Spirit Oracle, and I had spent time crafting things from her wood. But when I sat down to render her accurately in the winter months, I realized how little of her I had really seen in the dark half of the year. I spent a great deal of time just observing the ways that the winter branches looked, how the flower pods were clustered, and the growth habit of the small trees. I got out a magnifying glass, and went even deeper to really understand. And the witch hazel branch I had picked to draw from also had a grapevine growing around it, making it even more complex. As I drew this witch hazel and vine, I realized how little I truely knew these on such an intimate level. The way the bark was cracked and peeling on the fox grape…The practice of observing the witch hazel branch and flower, and then trying to render her exactly, took me to a new level of awareness. I noticed things I never had before. Hours and hours passed with this close connection and then the piece was done. My relationship with Witch Hazel and Fox Grape was deepened and never has been the same since.

The experience with Witch Hazel and Fox Grape opened up a door in me, realizing another way that I could combine the druid, bardic, and ovate arts through my botanical illustration work. In a second example, I’ve been working on an intensive study of mushrooms for the last few years. One of the mushrooms I’ve been working with deeply is the American Yellow Fly Agaric (Amanita Muscaria var. Guessowii). I find it fascinating that the red Amanita Muscaria / Fly Agaric is the most famous mushroom in the world, depicted in everything from Super Mario Brothers to Santa Claus. But, the yellow version that grows on the North American East Coast where I live is pretty much unknown. I knew I wanted to depict this beautiful mushroom so others could appreciate Guessowi the way that I did. For two summers, I sought the Guessowwi mushroom. When I found her, I spent much time communing with the mushroom–talking with her, making offerings, sitting with her, really just spending time to understand her energy. I also worked to observe all the details: how did the gills attach to the stem? How long and large was the stem? What were the different ways that the warts (veil remnants) would arrange themselves? How did this mushroom grow from the earth? What were the color variations? How did the volva (bottom part of the mushroom that attaches to the earth) look? How did the bugs eat this mushroom? What were the various stages of growth? What kinds of trees did the mushroom grow under? To do this, I spent a lot of time in the woods–I took tons of photos, spore prints, and samples, and just communed with the Guessowii. I did spirit journeys with her to learn her deeper wisdom. Also in 2023, I was involved in writing and leading a mushroom ritual at MAGUS 2023–where my group worked with visioning wiht the Amanita!

Through this deep observation process, and bolstered by a large group ritual as well as some of my own personal rituals, I became energetically aligned with the Amanita Muscaria var. Guessowwi. I learned this mushroom so well that I was seeing this mushroom in my dreams, thinking about the mushroom, anticipating where the mushroom may show up next, and feeling as though the boundaries between myself and the mushroom had been removed. Perhaps I became a bit obsessed with really doing this under-appreciated and little-respected mushroom justice.

By the time I sat down to paint the Guessowii in Fall 2023, I was more than prepared–I had a bank of over 50 photos. I had some dried specimens, but most importantly, I had Guessowii embedded in my spirit. I drew upon the bank of that knowledge to do my first sketches, working out the composition of the piece, and figuring out how many I wanted to depict and in what form. As I blended my paints and began to painstakingly and carefully layer washes and brush strokes, mask areas for the veil remnants, and so forth, I could feel the spirit of this mushroom guiding me. I had invested so many hours in learning her and honoring her that now we were together as I painted. The end result is probably the best piece I’ve ever done as a botanical artist–it took me over 50 hours. I felt like I lived side by side with Amanita as I did this piece. In the end, she was rendered as she wanted to be rendered. It also opened up a lot more spiritual work: energetic connections, spirit journeys, and much more. This was definitely an initiatory experience where I learned a great deal about her and many other wonderful mushrooms. And that work continues on!

Observation and Deepening Connection to Bardic Arts

Stepping back from the stories of these drawings, I wanted to share some more ideas and principles that could help someone interested in the bardic arts, drawing, painting, or even botanical illustration connect more deeply through observation and the synthesis of the bard, ovate, and druid paths.

Beings in Nature as Unique

When creating art from nature, each individual animal, insect, tree, mushroom, or plant has their own uniqueness–their own way of existing in the world. A maple is not just any maple, they are a specific maple. In the same way that you are not a general human but rather are a specific and unique human, a human being that is unlike any other. I think it is a sign of respect to render a specific being when you are engaged in the bardic arts. As you create any kind of art from the inspiration of that being, you begin to know them on a much more intimate level. Part of what you are doing is you are telling their story with your own work. You are essentially depicting them in some way, translating them for the world. Honor them, see how they want to be depicted, and do your best to represent that uniqueness.

Pick something you are excited to connect with deeper. I’m never going to have time to document the entire world around me, but I can pick beings in the ecosystem that really appeal to me, and that I want to build a deeper connection with. Find some being that calls to you and work to observe and build a relationship with. Maybe the first time, or even the 10th time, you are not necessarily ready to craft a bardic practice or piece around this being. But someday you will be! As my story of the Amanita Muscaria var. Guessowii shows, it can take you a long time to build the relationship but once you do, you can create wonderful bardic creations!

Bardic creation removes the boundaries between self and other. I think that one of the key takeaways for me on this journey was how engaging in this very deep connection with nature literally breaks down boundaries. This happened with the Guessowii–to understand and fully represent the mushroom, I had to become one with the mushroom. I really think there’s something special when you get deeply into the Awen–when you are flowing and really deeply embedded in the subject matter. In the case of botanical illustration, I am observing the mushroom more than I am drawing or painting, and while I’m doing that in a flow state, I just lose myself to the work. It is beautiful, it is magnificent, and it allows deep connections. The boundaries between myself and another being are removed. And even once the piece is done, I can bring myself back to that place.

Observation and interactions as central. My mother, also an artist, always told me to “look more than you draw” which is a lesson she had really learned in art school. Every time I sit down to depict something, I hear her words in my head (or sometimes there at the table, if we are creating art together). Most artists who have developed skills agree that observation is a fundamental part of the process of creating good art. The idea, here, is that in order to represent something in nature, you must deeply observe it till you know it as well as you know yourself. What this really is about is that we want the fullness of the natural being to express themselves, we are a vessel to allow that fullness of expression to come forth. By looking more than we draw (or paint, or write, or whatever else we are doing that is a bardic practice), we give more space for that being to speak through us. It is hard to put these concepts into words, but you will know it when it happens (and if you’ve experienced it, please share!)

Skill matters less than you think. Skill comes with practice, time, and making mistakes. You can be a beginner and still gain the benefits of what I’m sharing here–and everyone can get better at the bardic arts with practice. When it comes to drawing, the most important thing is that you slow down, look more than you draw, and really just work to depict what you see. You won’t get it right the first time, maybe even the 10th time, but if you keep practicing and trying, it will come. Like anything else, with practice, you can get much better. I’ve written a lot on this in my bardic arts series.

Bardic Creation –> Knowledge. The final point here is that I have never learned how to identify plants, trees, and mushrooms better than when I drew them. The ones that I have taken careful time to illustrate in this way are ones that I will always be able to connect to, always depict, and always identify in any setting. This bardic creation builds ovate knowledge.

I hope this glimpse into one artistic process has the Awen flowing for you! I would love to hear about your own bardic creations and the methods through which you may connect with beings in nature to depict them! I love hearing others’ stories and journeys of their bardic arts.

lovely lovely

Thank you 🙂

Hi Dana, lovely post today and wonderful art. It’s realistic yet somehow extra alive. I wanted to bring to your attention that the articles you linked for smartphone use and cognitive disturbance both concluded no association or contradictory results between the variables (though, in my own experience, they are certainly associated..). Thank you for your continued ‘Spiritual Advocacy’ 🙂 always a treat

Hi Hazel,

Thanks for sharing – I think they are associated, that’s for sure! I will link different articles when I have a moment to do so. Blessings to you! 🙂

An answer is in “The Twelve Blessings’, of the 5th.”Blessed are the Thanksgivers” in which the Devic Kingdom of universal service is taught. These nature spirits are in the foundation of Druidism.

Thank you, Graztite!

I can relate with what you say Dana about the art of observing and becoming one with the subject of observation. In my case I am passionate about the honeybees and other bees as a small medium size beekeeper. Observing the bees not only help me to understand and manage them better, it opened a connection with them that is going both ways. I am convinced that when I enter the bee yard they recognize me and let me know their needs. And our interaction is like a dance. Before leaving the bee yard, I honour them and bless them. I also ask the spirit of the bear to not hurt them and I feel it understands me in its natural way. This is my short opening through the world of the honeybees, bumblebees, wasps and other insects and animal life’s. Thank you Dana for making us more aware of our connection with the surrounding Life.

Hi Jean! I love that you are sharing the story of the bees. I used to keep bees when I left in Michigan but I haven’t taken up the practice since coming to PA. But I totally agree with you–the bees do get to know you, your voice, and they are very friendly to those who respect them. I love that you honor and bless them! Such a wonderful story. There’s so much sacred geometry in the beehive as well!

I am in awe of those that are able to sustain the focus needed to really engage with the Awen in the Bardic Arts. This area has always been a challenge for me. I consider myself creative but not artistic. When I started my Candidate year, I chose the Bardic path because this was something I really wanted to work on. The Ovate studies come easy to me. The Druid path is less easy but more so than the Bardic Arts. As a person of neurodivergence, it can be a real challenge to stick with any practice for long enough to truly feel that you have been able to develop it well. Perhaps I have not yet found my medium. I used to think it was dance but due to some injuries I have sustained over the last little while that has become out of reach, at least for now. I am working on drumming (Bodhran)but even then I am not sure how to connect it into the Awen, at least not yet.

Thank you for your post and images of your art work. Truly beautiful and Awen-inspiring!

Melissa

Hi Melissa!

Thanks so much for your comments! So I wonder about tackling it from another angle? One thing you might try is to identify when you get into a flow state in any aspect of your life (the flow state is what we druids would call the Awen, one specific aspect when things are just flowing for you, you are deeply embedded in it, you lose track of time, you are able to suspend your self-judgement, you are really immersed and present). See when and where that happens for you (it can happen with creative practices but also with cooking, video games, exercise, etc). Then once you get that feeling, see how you can bring it into your creative pracitices by setting up the right conditions for it. I can say more, and maybe I will–in my day job as a professor, I am currently undergoing some study of expert and emerging writers and I have a lot to actually say about flow states and awen and how to cultivate it! :).

I am also a person who identifies as neurodivergent (I have dyslexia). I do think things may be a little different for us (and different between us). Depending on the nature of your own neurodivergence, things like hyperfocus can really connect to the Awen. I have found for me that being able to focus is all about meaningful rituals. For my visual art, I typically do it at night, in a time and place where I will not be bothered. I have specific music, I light candles, I invoke the awen, and I really make it a ritualized experience. For my writing, I always write on Sunday mornings for about 4 hours; I have specific music that I play each week in the background; I drink tea or cacao, and I keep my door shut to stay in the Awen. It has taken me a while to figure these things out–how I best work, how to keep the dyslexia in a productive space rather than a disruptive space, and so on. Happy to chat more about it with you :).

In terms of research and strategies to help people with neurodivergence get into flow states and connect in that way, there aren’t many out there to share yet (at least not ones with scientific backing). Again in my day job, I actually am working on another study with one of my graduate students about neurodivergence and flow states–she’s also likely going to do her dissertation on the topic. So we are currently collecting data for that study to try to understand the relationship between these states and how neurodivergent people may access them…. Most scientific research takes a bit of time, so ask me again in about two years, haha! But at some point I’ll share some results on the blog once we have something to talk about. There’s not a good deal known about these now (especially for writers, which is what I typically study).

Hi Dana,

I will endeavour to pay better attention to when I get into Flow states and what the conditions were around them. I actually had one yesterday while working on a lesson plan for a course idea I was using for one of the classes in my Adult Learning Certificate. I find my Flow states tend to be around organizing, planning, or “hunting” (when I am out in nature scanning for things to see or find or when I am in a second hand store looking for treasures). If there is a topic that I am interested in involved then it is a lot easier. The Ovate Arts tend to be easier for me as it involves research and learning. Being AuDHD, the special interests are what get me engaged.

I feel like my art may be in writing but it can be hard to get my butt in the chair to actually commit thoughts to paper. I am great at generating ideas but not so great at seeing them through to completion (hahaha classic ADHD).

I would be very interested in your research once you have something to share. Anything that can help us neurospicy people access our gifts is, well, a gift.

Thank you very much for your insights; they are greatly appreciated.

Melissa

Hi Melissa, Thanks for your comment! I will share when I have more! In the meantime, one of the things that has helped some folks is using alternatives to the traditional typing or writing. For example, I have one student with both Autusm and ADHD, and what he does is walk around a park and dictate his writing into his phone, which he then transcribes and edits. The movement of the hike helps keep him going and talking aloud is easier than reading. I think a big part of figuring this out for yourself is really digging into understanding yourself and being really metacognitive about yourself and try to understand your needs. When do you focus best? What generally gets you into the flow? When can you do your best work? When shouldn’t you be trying so that you don’t get frustrated? Some people can use a regular schedule (that works well for me) but others need flexibility.

But I think the other thing is to do what you are saying you will try–paying attention to your own flow states and when they happen, so you can replicate those conditions and get into them in more often.

I will also stress here that modern technology, especially video-rich social media, are very detrimental to focus and flow. So many things are pulling at our attention and it can be very hard to avoid all of them and just write, paint, read, or whatever else!