Permaculture design is many things to many people–but ultimately, it is a system of design that works with nature rather than against nature. Permaculture uses principles to allow us to have a clear thinking process for creating resilient ecosystems, fostering care, and ultimately, building interaction and connection with the natural world. But it is so much more than that. One of the things that happen with people who pick up permaculture is that they start seeing the world differently. Way, way differently. All waste becomes resources. The soil web becomes a living thing that becomes sacred. You learn how to nurture seedlings and watch them grow. You attune to the ways of the earth and the cycles and seasons. Even for people who aren’t particularly spiritual, something fundamentally shifts and you grow much more attuned with nature and begin having spiritual experiences.

I remember a conversation I had with one of my permaculture-practitioner friends some years ago. He was like, “Hey Dana, I know you are a druid. So…uh…the plants are talking to me.” I smiled and said, “That happens.” There was a long pause. He said, “That’s not weird? I’m not crazy?” And I was like, “Nope, they talk to me too. They’d like to talk to all of us, but we aren’t all in a space to listen.” Long pause. “Hmm. Well, that’s something.” Then I said, “What are they saying?” This conversation stuck with me. Here was a person who had dedicated his life to practicing permaculture, offering consultations and designs to others, and to nurturing the earth. But a rigid religious upbringing had him disbelieving that there was more than matter, that there was a connection to spirit. But for someone who literally spent all of his days with plants, nurturing plants with care and dedication, and teaching others about plants–it isn’t surprising that he started hearing the voices of the plants. And he just needed someone to say, yeah, you aren’t crazy.

Permaculture practices intertwine you very deeply with the land. And since the land is full of spirits, it is not surprising that people who practice permauclture start having experiences like the one I’ve described above. In the next few posts, I’d like to build a conversation about the philosophy and practices of what I call “animistic permaculture”, a practice that interweaves a belief and reverence towards the spirit of all things with the ethics, principles, and practices of permaculture. This post is part of my animism series–if you want, please check out the first post two posts: introduction to animism and biocentrism/ecocentrism as a core part of nature spirituality. If you are interested in learning more about permauclture, you can see the following posts: permaculture through the five elements, permaculture design and intentionality, permaculture’s ethic of care, permaculture for the inner landscape, Sankofa, and a discussion of my first homestead using permauclture principles.

Animist Philosophy applied to Permaculture Ethics

Let’s start with animist philosophy. This is a brief summary of my longer post on animism from earlier this year, so please feel free to visit that post for a more full discussion.

At its basic level, animism is a belief in the spirit of all things, which includes living things (animals, plants), natural features (stones, rivers, mountains), but also things that come from nature (which is everything human created, everything present on this planet and beyond). Thus, animistic philosophy assumes that all things have spirit in the world and that world of spirits can be interacted with in various ways. As I described in my earlier post, here are some common threads that define animism.

- Recognizing and honoring the spirits present in things present in the world and universe, both animate and inanimate, both natural and created

- Recognizing the importance of interacting in a respectful way with those spirits; building the right relationships and connections with them, and learning from some of them as teachers and guides

- Recognizing that humans are part of nature, like any other animal, and that we have a set of tools we have evolved, including both our five senses as well as instinct and intuition

- Recognizing that we have to cultivate our own intuition, observation, and listening skills (inner and outer) so that we might effectively communicate with the spirit present in all things.

- Recognizing that our actions have a significant impact on others and that we can engage in right actions to behave in ways that honor the sovereignty of all beings

Animistic philosophy and practices surround working with spirits, learning from them, avoiding the bad ones, and recognizing our connected and collective places in the world. Animism facilitates a deep connection to the world of nature through the spirits that inhabit all things on earth, and thus, offers a deep connection to the “inner” world of nature. That is, animistic practices highlight the interaction of the physical and metaphysical world of nature.

Permaculture

Permaculture is a set of design tools, practices, and philosophies that offer guidelines for how to design, create, and inhabit spaces that work with nature and that regenerate ecosystems. Permaculture is meant to help cultivate resiliency, help bring people closer to the land, and work with natural cycles and systems for intentional interaction in the world. The overall goal of permaculture is recognizing that humans can be a force of good, and that we can work to heal our landscapes and allow them to provide for the needs of all inhabitants–human, insect, animal, plant, and otherwise.

Permaculture has a foundational set of three ethics (people care, earth care, fair share), which help guide decision making and allow us to orient ourselves in practices rooted in care. Moving into practice, permaculture principles are used to help us apply specific practices that build resilient ecosystems (like swales, hugelkultur, planting polycultures, sheet mulching, etc). The principles are guidelines for how you can design and interact with the landscape to create dynamic, bio-intensive ecosystems that are resilient and sustainable. There are between 12-20 principles, depending on which specific version of permauclture you use–here’s one that describes Holmgren’s principles.

In sum, permaculture offers a wide variety of tools to ethically connect to and work with the “outer” world of nature, including understanding ecology, cycles and seasons, plants, pollinators, and so much more. This is a very physically-based practice rooted in what our five senses can hear, see, and experience.

Why Animistic Permaculture?

So when we look at the above, we see that animism offers deep insight and connection with nature through the world of spirit, and permaculture offers deep insight and connection to nature through the physical world. If we combine these things, we can gain insight and connection to nature through both metaphysical and physical practices, which allows us to do better work on behalf of the land. In other words, while these are two powerful tools separately, together, they amplify and enrich each other. These two practices are highly complementary and fit beautifully together, particularly for those who are interested in nature spirituality. Also, as my opening story suggests, those practicing permaculture end up developing very deep relationships with the land–relationships that often end up having spiritual significance. Putting these two together

Over these last 15 years at two different homesteads, I’ve been exploring the intersection of these two philosophies and exploring how to bring them together. I’ve been an animist druid since 2005. I took up the practice of permaculture in 2010 by applying these practices to my homestead in Michigan. Later, I earned both my Permaculture Design Certificate (Sowing Solutions, 2015) and my Permaculture Teacher Training (Omega, 2017). My book Sacred Actions: Living the Wheel of the Year through Earth-Centered Sustainable Practices interwove many permauclture design principles, thinking, and ethics into earth-based spirituality. I’ve made a lot of mistakes, but I’ve also learned a lot. In the rest of this post series, I’ll share some of what I have come to understand as the basic practices and principles for engaging in an animistic permaculture practice and philosophy. Maybe someone else would do things differently, but these are the things that have worked for me. Feel free to share your own thoughts in the comments!

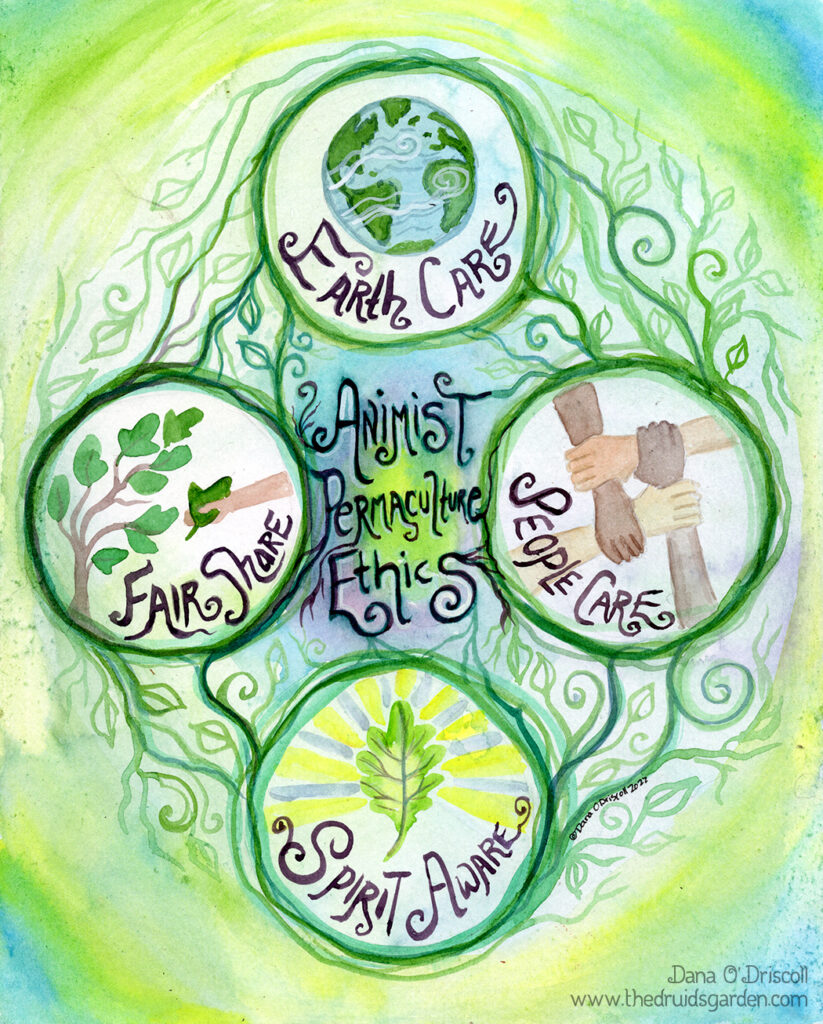

Animistic Permaculture Ethics: Earth Care, People Care, Fair Share, Spirit Aware

Permaculture ethics are the foundation upon which everything else in permaculture is built. They give us a compass, a way to make sure we are making the right decisions from the right place. The three permaculture ethics are:

- Earth Care: Care for the earth and all of her inhabitants. This would include caring for the land, the rivers, the soil web, all plants, animals, and other beings. But also caring thinking about the ecosystem and biosphere as a whole. While permaculture focuses on local issues and small solutions for individual practitioners, the principle of earth care applies to both the parts and the whole. In permaculture, earth care is a fundamental ethic–all things we do need to consider this ethic.

- People Care: Caring for the peoples of the earth. This includes considering people’s basic needs (food, shelter, water, warmth, community, creative outlets). In permaculture, we’d consider also how designs are able to meet both the needs of the earth and the needs of the people living there. People care also can be expanded more broadly to consider how we best care for each other and create a safe, supportive, and healthy world. Many also include “self-care” in people care–for to care for everyone else (land and people) one also needs to care for oneself.

- Fair Share: Taking only what you need redistributing excess or returning it to the land. This ethic speaks to the heart of how permaculture practitioners are trying to unwind capitalism and its excesses–thinking carefully about what you need to survive and thrive, but not taking more than that.

These principles are extremely useful to live and follow if you are also following an animistic philosophy, especially because of point #2 above–the need for respectful interaction and building right relationships with the land. By recognizing that care is a fundamental part of interacting with both the worlds without and within, you are essentially setting yourself up for positive relationships and connections with the world of spirit. If you are offering care in every interaction with plants, the spirits of those plants are going to work with you on the deepest level.

For an animistic philosophy of permaculture, care is a foundational principle but is not the end of an ethical system. Here’s why: one can care for something and still see it as a “lesser” being (perhaps rooted in narcissism). I’ve seen a lot of this in permaculture practices–you have a flock of chickens, you feed them and care for them and make sure they get free range time each day–but they are still lesser beings. Care in this case is insufficient–if that chicken has a spirit and you are both equals, is care enough? And even more problematic, sometimes care can become unbalanced or destructive. In fact, we see “care” being applied to all kinds of things that not care-oriented actions at all (“lawn care” being a great example–there is nothing care-oriented about chemical applications to eradicate dandelions).

In applying animism to permaculture, it is important to recognize not only care but equality–we are equal to all other beings and all beings are deserving of their sovereignty. The difference here is that this approach re-frames the relationship of humans and nature into a biocentric one rather than an anthropocentric one. Hence, I offer one more ethic to turn the triad into a quaternity: spirit aware.

Spirit aware: Spirit aware has several aspects. The first is that we are aware, engaging, and interacting with the spirit of all beings. The second is that in accepting that all things have spirit and we are equal in all things, we are able to offer due respect, reverence, and autonomy to all other beings. In theory, this seems straightforward but in practice, it requires some pretty big shifts. I’m going to delve into this in more depth next week, but I’ll share a small example here:

Let’s say you want to cycle your nutrients and take up the practice of humanure (yay!). If you are a permaculture practitioner, engaging in this practice would start with a period of observation and interaction where you can decide how to place and manage your humanure piles. You decide to place them over by some trees on the edge of your property. The site you choose is flat, it does not have drainage issues, and it is in the sun. It is also not too far from your home. You’ve considered earth care (no drainage to a local stream), people care (not too hard to carry buckets to the compost pile or tend it), and fair share (humanure practices allow for nutrient cycling, not waste streams).

But without talking to the spirits of the land, you may never know that the root systems of the nearby trees are very close to the surface, and situating your pile there would eventually kill the trees due to the weight of the piles. In talking to the spirits about the need for a humanure pile, they suggest a spot 20 feet to the left of the tree stand. This allows you still have an excellent location but does not cause any harm to the trees. The trees are happy because you’ve worked with them to find the best spot, and you still get everything you need to have a successful humanure practice.

The difference between scenarios 1 and 2 is that in scenario 2, the practitioner is spirit aware–asking the spirits for their guidance and making sure they are in agreement. The practitioner has taken the time to do this additional step, and it is a critical one. How can this step happen? Stay tuned for next week when we dig into a few permaculture principles and explore how to deeply connect with the Genus Loci, or spirits of place.

Humanure! Wow. I always learn so much for each and every post, Dana. Thanks!

P.S. I LOVE the new tarot deck and accompanying manual.

Hi Cynthia,

Yes! Humanure! I’m glad you are learning from these posts and love the new deck :). Blessings to you!

This is wonderful! I have always felt drawn to animism. I grew up in Washington state and Honolulu, Hawai’i, but, over 50 years ago, when I was a high school junior (1970-71), I went to Ireland for a year because my grandmother’s cousin was a nun and ran a convent school there, way out in the West, right on the Atlantic coast. I thought it was so very cool that the farmers at that time, when they plowed their fields, would plow around the fairy forts that some people had in their fields, they never plowed over them. I was told that would be a terrible thing to do, you never want to upset the fairies. I have wondered since if they knew their fairies because they (the Irish) were the indigenous people, whereas most of us here in America came from elsewhere, we are not familiar with the spirits of the land. In Hawai’i there are things that you just don’t do because you don’t want to upset the menehune.

I’m just starting to learn about animism, are there any books, besides your blog posts, where I can learn more? Thank you, Dana, I look forward to reading your posts every Sunday, I learn so much from you!

Hi Heather, thanks for sharing your story! A book I really like is Ani.Mystic: Encounters with a Living Cosmos by Gordon White. Lots of good stuff in that book :).

But I would say, you can learn more about animism by learning to talk to the spirits themselves and letting them guide you. They are the ultimate teachers and guides.

I am so very grateful for this enlightening inform. Thank you

You are welcome 🙂