I remember when I first saw a Tamarack tree. It was growing in a bog where I was hiking in late fall. I looked at the Tamarack tree in its golden splendor and wondered if the tree was sick or had gotten too wet–was this confier dying? It had knobby cones and branches, sitting there looking like it was in its death throes. When I commented on it to my friend, she responded, No, that’s just the tamarack tree, a friend of mine said, and we examined the tree growing on the edge of a beautiful wetland. Sure enough, a few weeks later, the tree was bare for the winter and only grew back in the spring. The Tamarack tree has a special place in the ecology in North America, especially as a mid-succession tree in very wet and swampy areas.

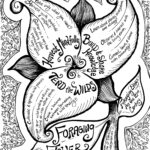

The Tamarack tree is known by many names: the Larch Tree, Eastern Larch, American Larch, Black larch, Red Larch, Hackmatack, Juniper cypress, Larch Tamarack. The term “larch” is an old German word like Hackmatack is the Abnaki word for “snowshoes”, suggesting one clear use of this tree.

This post is part of my Sacred Trees of Eastern North America series–here you can learn about the many wonderful trees upon our landscape. In this series, I explore the magic, mythology, herbal, cultural, and divination uses, with the goal of eventually producing a larger work that explores many of our unique trees located on the US East Coast (which I hope to have completed by early 2022–so you will be seeing a lot more tree posts!) For my methods using ecology, the doctrine of signatures, and human uses, you can see this post. Other trees in this series include Dogwood, Spruce, Spicebush, Rhododendron, Witch Hazel, Staghorn Sumac, Chestnut, Cherry, Juniper, Birch, Elder, Walnut, Eastern White Cedar, Hemlock, Sugar Maple, Hawthorn, Hickory, Beech, Ash, White Pine, Black Locust, and Oak. For information on how to work with trees spiritually, you can see my Druid Tree Working series including finding the face of the tree, seeking the grandmother trees, tree relationships, communicating on the outer planes, communicating on the inner planes, establishing deep connections with trees, working with urban trees, tree energy, seasonal workings, and helping tree spirits pass.

Ecology

Tamarack is particularly interesting from an ecological perspective for a number of reasons. First, while Tamarack is in the pine family, it is quite distinct because it is deciduous (and is the only conifer that is deciduous in much of its range). Thus, it drops its needles in the fall and follows the maples and oaks rather than its pine brethren. It literally serenades the sun with a brilliant yellow-orange color before it drops its needles for the cold months of the year. Tamarack also is a mid-succession tree, growing in bogs and marshy areas, providing food and habitat, and eventually making way to the Eastern White Cedar tree, the pinnacle species.

As John Eastman notes in The Book of Swamp and Bog, Tamarack has early rapid growth for the first 40 years of its life—it puts on growth very early in the season (around Beltane) and slows down by Midsummer. It produces small oval-shaped cones that usually appear on branches that are between two and four years old. These cones will be wind-pollinated in the spring by pollen cones that appear yellow on the same tree, and eventually mature, open, and drop seeds in the fall. As the tree loses its needles in the fall, these cones and branches look a little wicked and nobby, like an old woman! Like many other trees (Oaks) the Tamarack is strategic about seed production, producing bountiful seed only every 3-6 years. In the northernmost parts of its range, Tamarack may reproduce by way of the layering of lower branches on the ground and sending up a shoot.

As a mid-succession tree, Tamarack prefers nutrient-poor sites, including bogs, and its presence in a wetland may suggest it is growing at what Eastman notes is a “hinge line” or “transitional zone” between floating fen-mats in a bog and more grounded acidic bogs where plants like sundew grow. However, growing in such a wet environment does mean it develops shallow root systems and thus may be easily blown over by the wind. This bog environment also supports the germination of new Tamarack seeds—they often germinate on sphagnum moss. It also is frequently found with leatherleaf (promoting its germination through its ‘nurse tree’ status), and can be found with poison sumac, eastern white cedar (which succeeds it ecologically), shrub willow, and bog birch. Here in Western Pennsylvania, we often see the Tamaracks on the edge of acidic bogs that grow such wonderful and carnivorous plants like sundew and pitcher plants.

John Eastman also notes that in boggy environments, Tamarack is a “nurse tree” which allows it to produce shelter and biomass to allow other shrubs and smaller plants to grow in otherwise inhospitable conditions, particularly leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne Calyculata). Tamarack is also a favorite nesting site for Great gray owls as well as habitat for black-backed woodpecker, common snipe, common yellowthroats, and song sparrows.

A destructive pest—the larch sawfly (Pristiphoera Erichsonii) eats the Tamarack needles and has been responsible for destroying nearly all of the old-growth Tamarack trees in the Eastern US and Canada in the early 20th century. Tamarack has slowly rebounded from this destruction and you can once again find healthy stands of Tamarack in many parts of its range. This sawfly is an excellent food source for blue ays, sparrows, woodpeckers, cedar waxwings, grosbeaks, and sparrows. At least half of the seeds dropped are consumed by ruffed grouse, wild hare, red squirrel, gray squirrel, porcupine, and white-tail deer. These animals also consume the inner bark, which is nutritious (and also an emergency food for humans).

Human Uses

Tamarack is not a very sought-after wood these days, which is somewhat surprising, given its many uses–this is likely due to the historical loss of much of the Tamarack wood due to the larch sawfly and its inconvenient growth location in swamps and bogs. Still, the wood is heavy, hard, strong, coarse-grained, and has excellent rot resistance, particularly in wet conditions or when exposed to water. It has been traditionally used for many applications where rot resistance matters: fence posts, telegraph poles, railway ties, building materials, ladders, floorboards, and various kinds of poles. In 1938, it was noted that it has been used extensively for building ships, especially for parts of ships that are directly exposed to water.

According to Charlotte Erichsen-Brown in Medicinal and Other uses of North American Plants, the Tamarack had a wide range of uses for the Native American people and early white Colonists of North America. The Ojibwe used Tamarack resin to seal boats (similar to white pine) and the bark to cover their wigwams. The roots were used to weave bags and sew the edges of canoes as the Tamarack root fiber is particularly durable compared with other materials. The inner bark was used as an emergency food by many, as nearly all conifers have nutritious inner bark. One of the things that Native Peoples often used tamarack wood for was boiling maple sap—it is a hot, fierce wood that burns brightly—exactly what you need for a good sap boil!

Turpentine can also be made from Tamarack trees. The trees were tapped, in a very similar method to maple tapping, and the sap collected–this is the process of making a “gum” turpentine as opposed to a “wood” turpentine (which is done with the stripped bark). After the trees were tapped, the gum is distilled to produce a volatile oil that was strong and mixed with paints and varnishes for lasting quality. This same sap was also used for all manner of wound healing in earlier times in North America.

Medicine and Herbal Qualities

Unfortunately, while Tamarack had a range of traditional colonial uses, it has limited coverage and uses in present-day herbals.

The best references to the medicinal qualities of the tree can be found in ethnobotanical sources. Erichsen-Brown notes that that the Ojibwe used the crushed needles and bark similar to how they would use white pine. Likewise, the Potawatomi used the roots and bark from the trunk. The fresh inner bark is used for poulticing wounds/inflammation; seeped bark as a tea. It was used also as horse medicine; the inner bark was shredded and mixed with other feed grains to create a soft and supple hide.

The only coverage of the plant I could find in modern herbal sources was through M. Grieve’s Modern Herbal, which offers insight on the bark, which she notes is used as a laxative, tonic, diuretic, and alternative. She notes that it has widely been used for treating issues with the liver, rheumatism, jaundice, or dysentery. Her dosage indicates that 2 tablespoons of the decoction of the bark are necessary.

I have been experimenting with some of the Tamarack’s medicine in the form of salves for bruises (one traditional use) and they seem pretty effective. I’ll keep updating this post as I try some of the other traditional uses and if I find more information.

Magical Uses in the Western Tradition

Part of the reason I spent so much time in this post on ecology and human uses is that–unsprisingly –there is no real tradition of the magical use of the Tamarack tree. While this isn’t surprising (as many of the trees I am covering in this series lack such coverage), it does mean that we have to use the tree’s ecological functions to ascertain its magical meaning. It is not found in the Hoodoo traditions, nor in the traditional western occult texts, nor in the PA dutch and other folk magic traditions. (It you have info I don’t about this, please share!)

Magical and Divination Qualities of Tamarack

Addressing Stagnation. Tamarak’s medicinal and ecological function includes it growing and addressing a range of stagnant, watery conditions. In the body, stagnation leads to all kinds of illness and atrophy; in the wild, stagnation can lead to anaerobic bacteria formation (stinky, nasty piles of compost for example). One of Tamarak’s key magical and divination qualities, then, is being able to address this stagnation and help get it flowing again.

Standing up to emotional challenges. Flowing from the first meaning, the second key meaning of Tamarack is helping you endure a stagnant emotional condition. For example, perhaps you are in a difficult family circumstance that seems to keep repeating itself, you are dealing with cycles of abuse, PTSD, or other draining and long-standing emotional conditions. Tamarack will help you stay the course during this time and offer you strength to endure (and not rot away in the mire!)

Surprise. A final divination and magical meaning this tree suggests is that while it is in the pine family and is a conifer, the tree does not follow the same pattern as most other pines–rather, in a surprising twist, it drops its needles after serenading the sun. Seeing Tamarack in a reading may suggest to you that things are the opposite of what you expect and to be surprised with the outcome.

I hope that this post brought you happiness and joy as spring turns to summer. And perhaps you will have an opportunity to meet the wonderful Tamarack tree and share in her magic. Blessings!

Reblogged this on Good Witches Homestead.

Thanks for the reblog! 🙂

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Reblogged this on GrannyMoon's Morning Feast.

I love these posts and am so looking forward to the book compilation. I’m in southern Illinois so many of these sacred trees of PA also live with me. My tree teachers/sisters are various oaks of course but the understory has revealed some others like holly, sassafras’s, chokecherry and pawpaw. Blessings on your service to our sacred teachers. Yvonne

On Sun, May 23, 2021 at 7:32 AM The Druid’s Garden wrote:

> Dana posted: “I remember when I first saw a Tamarack tree. It was growing > in a bog where I was hiking in late fall. I looked at the Tamarack tree in > its golden splendor and wondered if the tree was sick or had gotten too > wet–was this confier dying? It had knobby co” >

Yvonne, I am glad you are enjoying this series! It is sort of amazing to me, once I’ve gotten beyond the big overstory trees like pine, oak, or cherry, just how little we have on the magic of the trees here in our own landscape. I’m glad that this project is speaking to you!

In fact, I’m working on the PawPaw post today! 🙂

Greetings,

I cam across this blog when searching online for methods of collecting resin from trees. I am wondering if there is someone I could contact about this matter.

Thanks,

Robert

Hi Robert,

You are welcome to contact me here on the WordPress Blog. Or you can email me if you’d like – adriayna (at ) yahoo (dot ) com. Thanks 🙂

[…] posted on The Druid's Garden: I keep in mind once I first noticed a Tamarack tree. It was rising in a bathroom the place I […]

One thing I missed in your post on Larch are First Nations’ legends concerning Larix laricina. I think many Nations’ legends of Larch’s selfishness and being brought low, only to be redeemed and become the great medicine tree and great soul that she is today, is not only a reflection of her ecological function and physical attributes but also of her innate nature. Much of the European’s Larchs’ mythology and spiritual uses can be understood through the interpretation of the legends, as the Larixs are similar as one tree tribe. I really enjoy the work that you are doing and comment from the happy place of a fellow animist. 🙂

Thank you for sharing this! 🙂

Hello! thank you for this comment. Do you have a source for the First Nation’s legend of the larch tree? I would love to follow this story to its origin. thank you

This site has a great database of many stories from Indigenous tribes: https://www.firstpeople.us/