For three years, I have had my eye on our American hazel bushes here at the homestead. When we first moved to the property, much of the understory was damaged with the logging the previous owners did and it took time for the hazels to recover. Thus, for the last few years, I’ve watched the hazels grow taller and larger each year and kept looking excitedly for any signs of nuts setting. This past fall, I was delighted to find handfuls of delicious wild American hazelnuts and connect with the incredible wisdom that they offer.

While Hazel is a critically important tree in the mythology and magical tradition of Druidry and in Europe more broadly, The Hazel is one of the sacred trees identified by the druids as a tree tied to wisdom and the flow of Awen, and it is one of the sacred trees found in the Ogham. But here in North America, despite having our own native hazels (American Hazelnut and Beaked Hazelnut), we often turn our eyes towards Europe’s mythology and understandings. Thus, in this post, I’d like to share more about the American Hazelnut, and the ecology, uses, herbalism, magic, and myths of this most sacred tree.

This post is part of my Sacred Trees in the Americas series. In this series, I explore the magic, mythology, herbal, cultural, and divination uses, with the goal of eventually producing a larger work that explores many of our unique trees located on the US East Coast. Other trees in this series include Witch Hazel, Staghorn Sumac, Chestnut, Cherry, Juniper, Birch, Elder, Walnut, Eastern White Cedar, Hemlock, Sugar Maple, Hawthorn, Hickory, Beech, Ash, White Pine, Black Locust, and Oak. For information on how to work with trees spiritually, you can see my Druid Tree Working series including finding the face of the tree, communicating on the outer planes, communicating on the inner planes, establishing deep connections with trees, working with urban trees, tree energy, seasonal workings, and helping tree spirits pass.

Ecology

The American Hazel is an understory tree that is native to the eastern half of the United States and into the Eastern half of Canada. The second native Hazel we have is the Beaked Hazel (Corylus cornuta), which has an even wider range in North America–both have fairly similar growth habits.

As a deciduous tree, the American Haze produces brownish-yellow foliage in the fall and is in the birch (Betulae) family. It can tolerate a wide range of soil and light conditions, including acidic or alkali soil and full sun to part shade. I’ve primarily seen it in the Allegheny mountain region of Western PA either as a full shade understory tree or along part-shade edges of damp deciduous forests. It has simple, alternate leaves that are shaped like a heart or oblong (which have some variation from region to region) and tiny little hairs running up the branches. The leaves are toothed and soft to the touch.

The Hazel only reaches a height of about 12-15 feet at maturity and spreads in a thick cluster where many smaller hazel trunks will grow out of a single root structure and span 10 feet or more. Thus, when you find one American Hazel tree cluster, you will often find many more Hazel grows quickly once planted; it can grow 12-24″ in a single season. Within seven years (planting from seed), it can produce its first crop of hazelnuts and most of these trees can produce nuts for over 40 years.

While hazels will produce both male catkins and female flowers on the same plant, they are not self-fertile, and thus, require several in order to properly reproduce. Thus, if you are planning on planting some, keep this in mind. The male catkins are visible all winter. In early spring, like spicebush, tiny red clusters (the female flowers) burst forth. After pollination, the male catkins dry and drop off leaving the female flowers to transition into nut pods that feature two large green bracts (one of the characteristic looks of the hazel). When the nuts are ripe in the fall (here, this is sometime in September), the green bracts start to go yellow and then brown. An easy way to spot these in the fall as just as the leaves are beginning to come down, you can

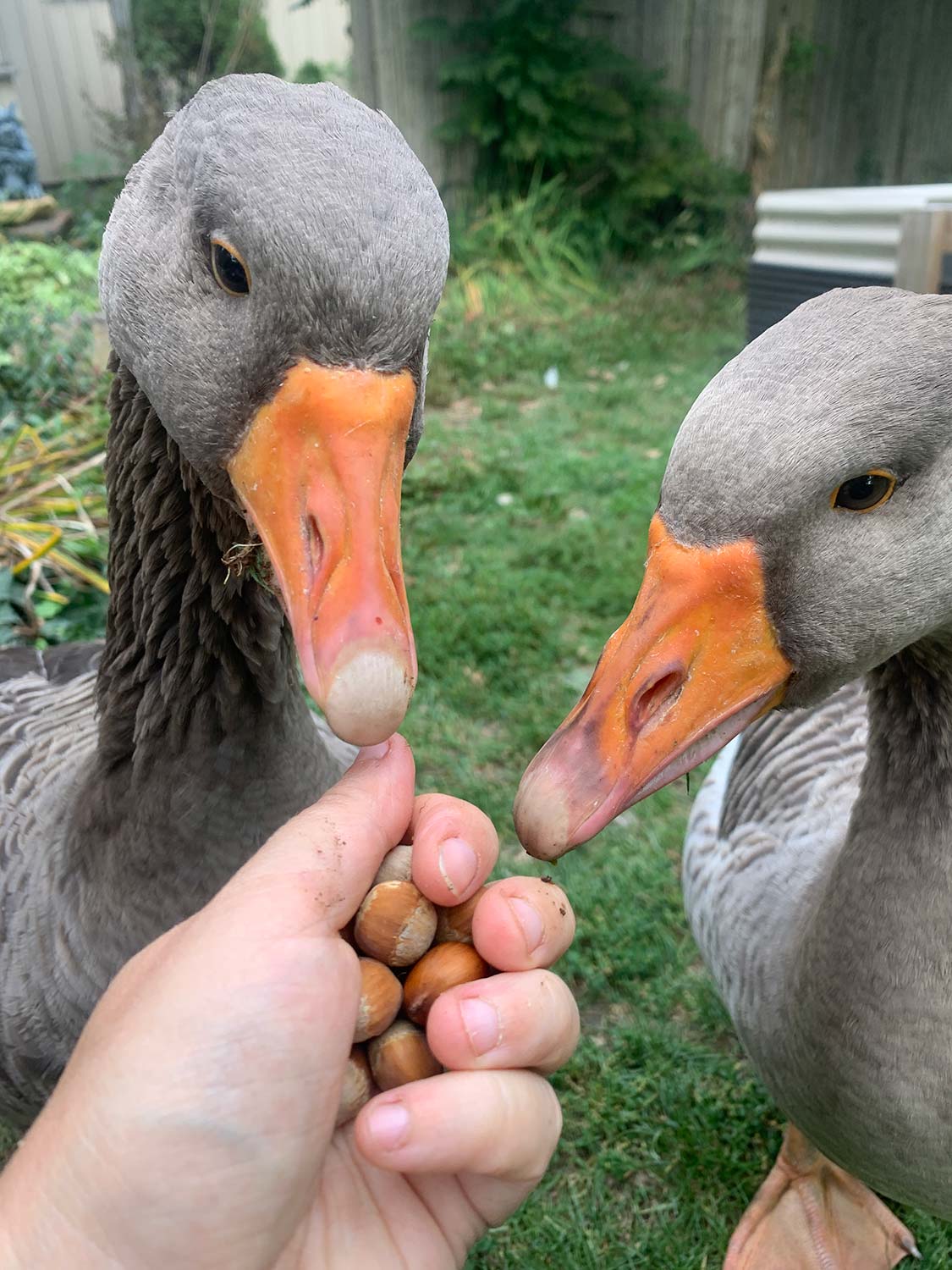

Not only are the nuts delicious for humans, they are also highly sought by wildlife including squirrels, deer, turkey, woodpeckers, grouse, pheasants, beavers, fox, quail, and even blue jays. The male catkins, which stay on the trees all winter, are foraged by ruffed grouse during the lean winter months. Of course, like all other nuts in the region, nut weevils may be present (in this case, hazelnut weevils, curculio neocorylus). When you harvest hazels, its a good idea to let them sit for about 7-12 days and let the weevils come out. I return those to the land and enjoy the rest!

Food Uses

Most obviously, American Hazel produces delicious nuts and they are well worth seeking out if you do any foraging. Here is a great blog post on foraging for either variety of hazelnut that grows wild in the Americas: beaked hazel or American hazel. It is important to realize that the wild American Hazelnut is going to be smaller and more flavor intensive than the domestic counterpart; this is because most commercial hazelnuts sold are either European Hazels (about twice the size of American Hazel) or are hybrids. This is a very common thing among wild foods: the domestic varieties have been bred for size or hybridized, but often at the expense of flavor. A wild hazelnut will be so rich and flavorful compared to what you will find in the store (also true of wild strawberry, wild raspberry, etc).

Hazelnuts are able to be enjoyed directly from the tree. When you harvest them, simply peel off the catkins and you will be left with a nut surrounded by a thin (and easy to crack) shell. This is for American hazel specifically; the beaked hazels are much harder to shell and you usually have to rot the catkins away (Sam Thayer discusses this technique more in his You can eat them like this and store the nuts for up to 18 months in a cool place. If you want to take it a step further, you can I prefer to roast them slightly in the oven. To do this, you can crack the nuts and then roast them at 275 for 15 or so minutes–you want them slightly brown but not scorched. Or, if you have a wood-burning stove, you can just put your nuts on the top of the stove for 10 -15 minutes in their cracked shell and roast that way. If you have enough, you can grind up your roasted nuts and make incredible nut butter. Beyond roasting, you can use American Hazelnuts in any recipe that would call for commercial hazelnut: cookies, ice cream, sprinkled over salads, etc.

In Edible Plants of Eastern North America (1943), Fernald and Kinsey note that American Hazels were harvested extensively in the country and ground into a meal, which was then baked into a cake-like bread.

John Eastman in Forest and Thicket notes that the hazelnut oil, when pressed, can be used for perfumes and that the wood has traditionally been made into charcoals for drawing.

Other Uses

Within the permaculture community, Hazelnuts are an important crop for food forests and to support perennial agriculture. The entire idea behind perennial agriculture is that we can plant trees or other crops once and then gain many harvests, and cultivate a food forest rather than an annual vegetable garden. This has made nut crops, like chestnut and hazelnut, important symbols in that movement.

American Hazel, like all other hazels, has the ability to be coppiced. This means that once established, you can cut the tree back to the roots and harvest the thin trunks. There are coppiced hazels in parts of Europe that have been a continual source of raw material for centuries; this is a very sustainable and regenerative practice. Within a few years, the hazel will send up new wood and regrow.

Because Hazels are understory trees without thick trunks, most of the wood applications in Hazel have to do with their ability to produce lots of small, flexible branches and be coppiced. Hazelwood has been traditionally used for building small structures like fences, in wattle and daub natural construction, in building the traditional coracle boat, or for creating supports in a garden.

Native American Uses

Erichsen-Brown notes in Medicinal and other uses of North American Plants: A Historical Survey with Special Reference to Eastern Indian Tribes the extensive uses of Hazelnut among Native Americans in North America. Archeological evidence demonstrates Hazelnuts at an Iroquan site and in caves in what is now Ohio in Pennsylvania; this evidence dates from 800-1400 AD that large amounts of nuts were consumed by the tribes living here. Hazelnuts were dried, ground up, made into meals and gravies, and used to create mush. The oil was also used for hair and mixed with bear grease by the Iroquis.

Medicinally, the Hurons used a bark poultice of the hazelnut tree for ulcers and tumors. The Chippewa used hazel and white oak roots combined with the inner bark of chokecherry and the heart of ironwood for hemorrhages or serious lung conditions. Similarly, the Ojibwa used the bark poultice on cuts.

The inner bark was used by the Chippewa (along with butternut or inner bark of white oak) as a dye for blankets, rushes, and more. A recipe given in Erichson-brown is to use the hulls from the nuts to set the black dye of butternut when boiled with tannic acid. The Chippewa and the Ojibwe also made drumsticks of hazel along with brooms and twig baskets. The bark was also used to expel worms, in a similar fashion to walnut.

Hazel does not appear to feature much in the legends that I have read of Native American traditions. Since so much was lost due to the cultural and physical genocide of many tribes, however, it is hard to say what magic the Hazel may have had to these amazing peoples.

Hazel in the Western Magical Traditions

In Celtic mythology, Hazel was an extremely important tree and tied directly to the mythology of the druid tradition. In Irish mythology in the Finnean cycle, it is written that the Hazel tree is the very first tree to come into creation and that all of the knowledge of the world was contained in the Hazel tree. The Salmon of Wisdom (An Bradán Feasa) lived in the Well of Wisdom (Tobar Segais) which was surrounded by nine sacred Hazel trees with their wisdom-containing nuts. The nuts of the trees dropped into the water and eaten by the Salmon. The first person to catch and eat the Salmon would gain this knowledge. While many tried and failed, Finnegas spent seven years fishing and finally caught it. Finnegas sets his apprentice, the young Deimne Maol, to prepare the fish but not to eat it. Deimne sets the fish upon a spit and begins to cook it. In the process of cooking when the fish is nearly prepared, Deimne burns his thumb and puts his thumb in his mouth to ease the pain–and, of course, acquires all of the knowledge from the Salmon of Wisdom. Deimne becomes Fionn mac Cumhaill (Fin McCool), the leader of the fabled Fianna and hero of many Irish tales. Those students of Welsh druidry will note the similarities between this story and the one describing how Gwion became Taliesin. In modern revival Druidry, the wisdom of the hazel and the Salmon of Wisdom in the sacred pool remains very important symbols of our tradition.

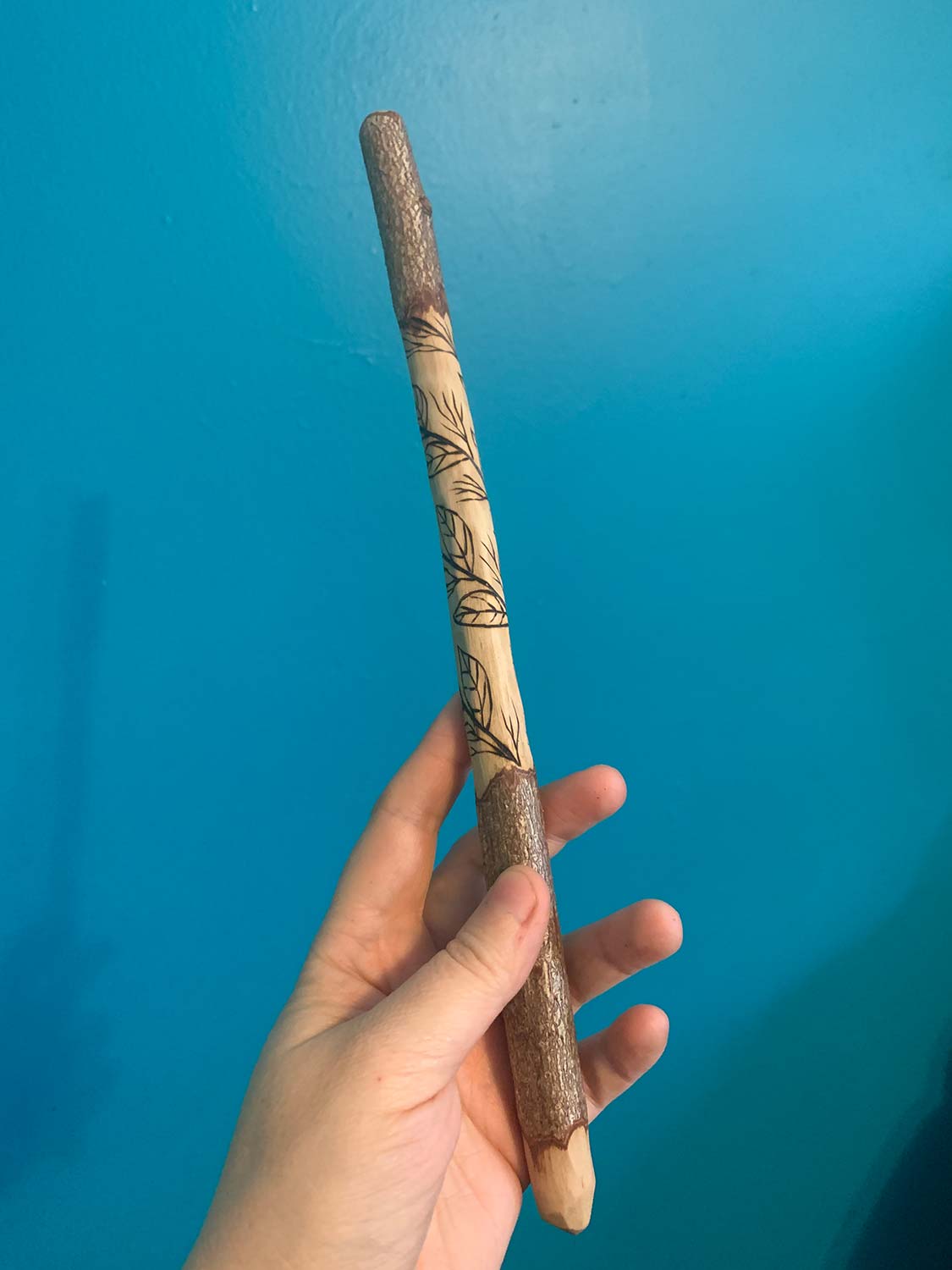

Greer notes in the Encyclopedia of Natural Magic that Hazel has been used by magicians extensively throughout the West. Hazel is best used for wands and various kinds of divination rods and sticks (including dowsing). Cut the hazel with a single stroke with a consecrated knife at sunrise on a Wednesday for the best effect. Hazelwood makes an excellent wand and transmits energy effectively. Greer also notes that the nuts are excellent for communing with Mercury or connecting with Mercurial energies. One area that I disagree with Greer about, however, is that he says that Witch Hazel (Hamamelis Virginiana) and American Hazel are interchangeable. In my own experience, while witch hazel became the traditional wood for dowsing rods, I do not believe these woods serve similar functions on the landscape, and thus, I have found them to have different magical qualities.

In Celtic Tree Mysteries, Steve Blamires notes that the wood was used for dowsers extensively in the British Isles. In the Ogham, hazel is noted as the “fairest of the trees” and is tied to the flow of Awen, divine inspiration, particularly for the crafting of poetry. The other thing Blamires notes, which I have not been able to find an original source for, is that there is a ritual by the druids called “Diechetel Do Chenaid” where chewing hazelnuts were used for inspiration or to learn of something lost. I’m not sure if this ritual comes from myth or is speculation, so if anyone knows more about it, I would appreciate them sharing! Finally, Hazel wands (probably due to their Mercurial connections) were used as a symbol for a herald.

Hazelnut does not appear to have any uses within other folk traditions in the Americas, such as Hoodoo.

The Divination and Magic of the Hazel

Given everything above: the ecology, food uses, and mythology surrounding hazel, I’d like to propose the following three divination and magical uses for American Hazel.

Wisdom. While the mythology surrounding wisdom and creative inspiration comes from the British Isles, I think that mythology is strong for those of us practicing druidry in the US today. Thus, the American hazel is associated with Wisdom and knowledge, just as the British counterpart.

Creative Inspiration and the flow of Awen. Flowing inspiration of all kinds comes from working with the Hazel tree. Be inspired by the joy and connection this tree offers. Eat of the hazelnuts and find your inspiration! Bring hazel into your life through the crafting of wands, amulets, and more to encourage that flow.

Renewable tools. Hazel offers many tools and gifts for those seeking a sustainable lifestyle and to transition to more sustainable practices. Thus, Hazel offers the knowledge and uses of its many tools and the idea of sharing these practices widely. Hazel offers much hope for us to think about how to transition from mono-crop agriculture that is destroying the land to instead, work with the energy of the hazel, a tree that can be infinitely renewable and incredibly generous.

Friends, readers, I would love to hear your experiences with the Hazels where you live! What have you experienced or discovered about them?

Reblogged this on Blue Dragon Journal and commented:

I love these little trees. They grow in the Pacific NW and are quite delightful. Their nuts are hard to find as the local wildlife get there first!

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Dear Druid, I really enjoyed this post! We bought a small piece of land outside Punxsatawney. And I’d like to take an ecological, permacutural, functional aesthetic approach to our upcoming garden. You’ve inspired me to introduce these hazels, as i thin out the edges of the regenerating forest. (Clearcut #2, 3, or 4?)

I am a Western Pa native, and self-taught naturalist. I talk to trees, plants, soils and water, sense their Beingess and increasingly feel their frequencies.

Suzy, awesome! I wrote you an email (and deleted your contact info before sharing your comment). I would be delighted to connect and so happy to hear what you are doing up in Punxy! :).

I enjoy your posts and your plant spirit oracle cards, but it makes me sad that many of the vegetal life is focused on the east coast, and I am unfamiliar with them. I live in Denver, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, and the vegetation is very different here. Do you know of any druids publishing about this area of the country? P.S. I love the deck anyway!

Hi KDKH! Thanks for your comment. I’m rooted in Pennsylvania, so all of my knowledge comes from there. I wouldn’t be the right person to write about Denver plants….but maybe you are! I don’t know anyone now that is doing that work, but if you look at this post, I outline my methods: https://druidgarden.wordpress.com/2021/02/21/wildcrafted-druidry-using-the-doctrine-of-signatures-ecology-and-mythology-to-cultivate-sacred-relationships-with-trees/

Blessings!

I do well with trees as individuals (but not archetypes), but struggle with the smaller plants. This is why I love your cards! I’ll check your article and see how i an progress. Thank you.

The practices between plants and trees are the same, but trees have a bit more force of personality and strength. But some perennial plants can be very powerful as well! The herbs, perhaps more than any of the plants, are used to working with us :).

Reblogged this on finding serendiipitii.

Thanks for the reblog!

Reblogged this on Good Witches Homestead.

Thanks for the reblog!

Have you considered (or, rather, will you consider) releasing the Sacred Trees series as an e-book, or self-published book-for-order? I’d really like to have these in print form and, while I certainly can do them individually, I’m guessing many others would be interested in the same. Just a thought!

Yes. This has always been my goal with the series! I have about 5 more trees to finish (which I will do in the next 1-2 months) along with some other writing to complete. My plan is to complete this book (and the connected oracle, called the Tree Alchemy Oracle) by the end of 2021. We will be releasing an Indegogo campaign for it as well! Stay tuned :).

Wonderful! I look forward to that!