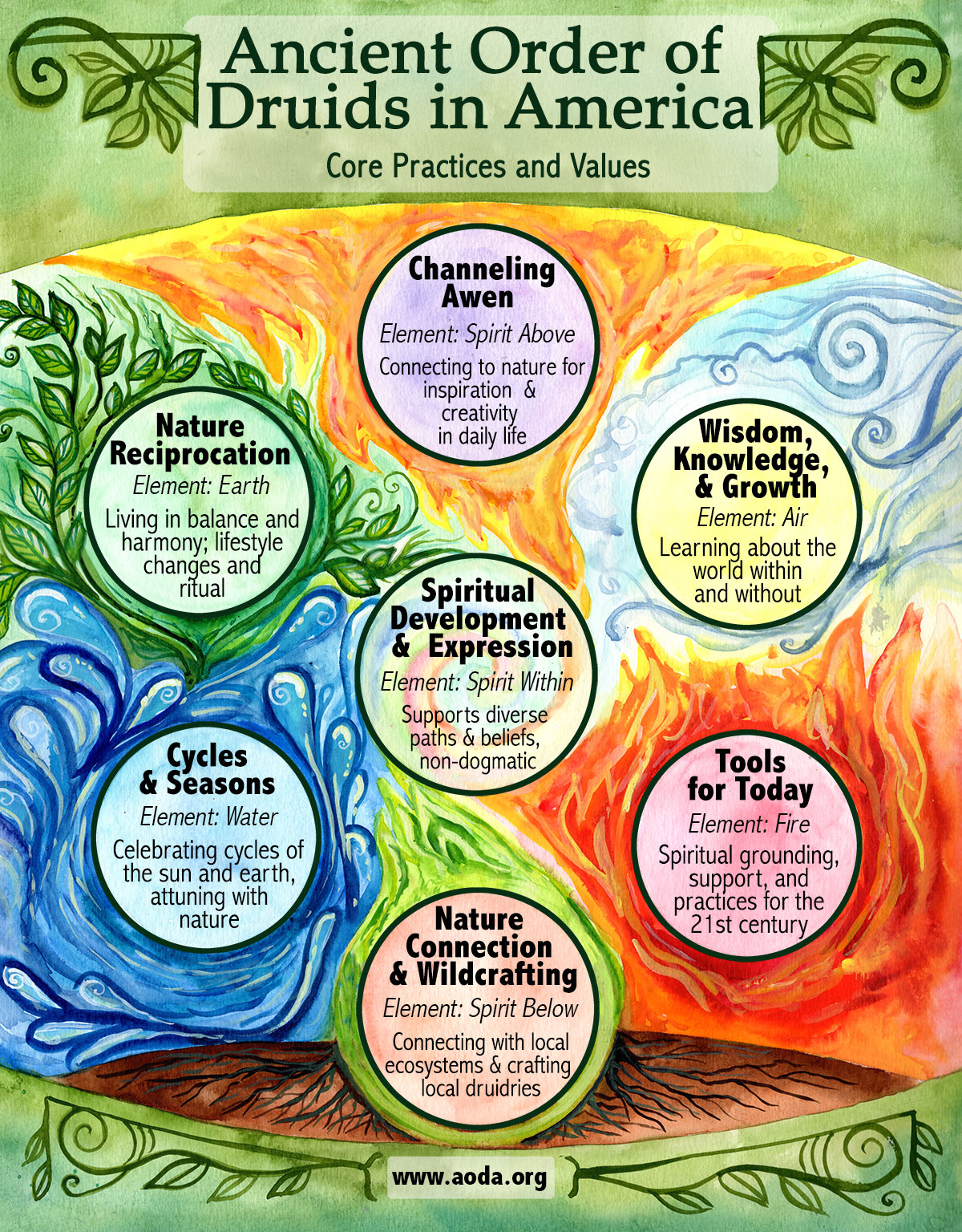

One of the strengths of AODA druidry is our emphasis on developing what Gordon Cooper calls “wildcrafted druidries“–these are druid practices that are localized to our place, rooted in our ecosystems, and designed in conjunction with the world and landscapes immediately around us. Wildcrafted druidries are in line with the recently released seven principles of AODA, principles that include rooting nature at the center of our practice, practicing nature reverence, working with cycles and seasons, and wildcrafting druidry. But taking the first steps into wildcrafting your practice can be a bit overwhelming, and can be complicated by a number of other factors. What if you are a new druid and don’t know much about your ecosystem? What if you are a druid who is traveling a lot or is transient? What if you are a druid who just moved to a new ecosystem after establishing yourself firmly somewhere else? This post will help you get started in building your own wildcrafted druid practice and will cover including using nature as inspiration, localized wheels of the year, pattern literacy, nature and relationship, and finding the uniqueness in the landscape.

Prior to this post, I’ve shared some of my earlier ideas for how you might develop a localized wheel of the year, consider the role of local symbolism, and develop different rituals, observances, and practices in earlier blog posts. The three linked posts come from my own experiences living as a druid in three states: Indiana, Michigan, and now Western Pennsylvania. For today’s post, I am indebted to members of AODA for a recent community call (which we do quarterly along with other online events). In our 1.5 hour discussion, we covered many of the topics that are present in this post–so in this case, I am presenting the ideas of many AODA druids that flowed from our rich conversation. For more on upcoming AODA events that are open to AODA members and friends of the AODA, you can see this announcement.

Nature as Inspiration and for Connection

While the principle of wildcrafting seems fairly universal, in that all druids find some need to wildcraft to varying degrees, there is no set method for beginning to engage in these practices or what they specifically draw upon in their local landscape. The details vary widely based on the ecosystem and the individual druid’s experiences, history, culture, and more. What an individual druid chooses to follow is rooted in both the dominant features of that landscape, what they choose to focus on in the ecosystem, and how they choose to interpret and build a relationship with their landscape. Here are some of the many interpretations:

- Following the path of the sun and light coming in or out of the world (a classic interpretation) and looking for what changes in the landscape may be present at the solstices and equinoxes

- Following clear markers of the season based in plant life: tree blooming, sap flowing, colors changing, tree harvests, dormancy, and more

- Following clear markers of migrating birds and/or the emergence or stages of life for insects (monarchs, robins)

- Following animal patterns and activity (nesting behavior, etc)

- Following weather patterns (e.g. time of fog, monsoon seasons, rainy season, dry season, winter, summer, etc)

- Following patterns of people or other natural shifts in urban settings (e.g. when the tourists leave, patterns of life in your city)

- Recognizing that some places do not have four seasons and working to discover what landscape and weather markers mark your specific seasons

- Drawing upon not only ecological features but also cultural or familial ones (family stories, local myths, local culture)

Transient druids or druids who travel a lot may have a combination of the above, either from different ecosystems that they visited or from a “home base” ecosystem, where they grew up or live for part of the year. There is obviously no one right or wrong way to create your wheel.

Another important issue discussed in our call tied to using nature as inspiration is viewing nature through a lens of connection rather than objectification. When we look at a tree, what do we see? Do we see the tree as an object in the world? Perhaps we see it as lumber for building or as a producer of fruit for eating. But what if, instead, we thought about the interconnected web of relationships that that tree is part of? What is our relationship with that tree? Thus, seeing nature from a position of relationships/connections and not just seeing nature as objects is a useful practice that helped druids build these kinds of deep connections with nature.

Wheel(s) of the Year: Localizing and Adapting

The concept of the wheel of the year is central to druidry. Druids find it useful to mark certain changes in their own ecosystems and celebrate the passage of one season to the next–practices which we’d define in terms of a wheel of the year. But to druids who wildcraft, the wheel of the year should be a reflection of nature’s cycles and seasons, things that are local and representative of the ecosystems that they inhabit. While many traditional wheels of the year assume either a fourfold or eightfold pattern and are based entirely on agricultural holidays in the British Isles and the path of the sun, this system does not map neatly–or at all–onto many other places of the world. The further that one gets from anything resembling UK-like temperate ecosystems, the less useful the traditional wheel of the year is. The disconnection and divergence encourage druids to build their own wheels of the year.

Druids describe widely divergent wheels of the year in different parts of North and South America. Some reported having only two seasons (rainy and dry) while others reported having up to 7 different distinct seasons in their wheel. Wheels of the year might be marked by some of the kinds of events described in the bullet points above: the return of a particular insect to the ecosystem, the migration of birds, the blooming of a flower, first hard frost, the coming of the rains, and so forth. I shared my own take on the wheel of the year here, and also wrote about my adaptation of Imbolc to my local ecosystem and local culture–these are two examples that might be useful to you. Even if you live in an ecosystem that isn’t that divergent from the classical wheel of the year, you still may find that you want to adapt parts of it to your specific experiences, practices, and connections.

From my earlier article on the wheel of the year, here are some practices that you might do to start building your own wheel:

- Nature observations: You might start by observing nature in your area for a full year and then noting: what is changing? What is different? How important are those changes to you?

- Interview the Old Timers and Wise Folks: Talk with the old farmers, wise women, grannies, and grandpaps in the area who have an innate knowledge. Ask them how they know spring has arrived, or that fall is coming, or what they understand to be the seasons. You might be surprised at the level of detail you get!

- Look to local farms and agriculture. Most traditional agricultural customs and products are directly dependent on the local ecosystems. You can learn a lot about important things that happen in your local ecosystem by paying attention to the agricultural wheel of the year and what is done when. If you have the opportunity to do a little planting and harvesting (in a garden or on your balcony) you’ll also attune yourself to these changes.

- Look to local customs and traditions. You might pay attention to regional or local fairs and festivals and/or look at regional calendars to see what the important dates are. Some of these may be contemporary customs from much older traditions (like Groundhog Day) or customs that used to take place but no longer do (like Wassailing in January). Reading about the history of your region, particularly, feasts, celebrations, and traditional activities might give you more insight.

- Consider family observances. Some families develop their own traditions, and some of those might be worth considering. For others, family traditions are often religious and may belong to a religion that you no longer want to associate with, and that’s ok too.

- Consider where the “energy” is. What is this season about? Where is the energy and power in the land at present? What is changing? Observation and interaction will help.

- Speak with the nature spirits. Perhaps the most powerful thing you can do is to connect with the nature spirits or spirits of the land and see what wisdom they have for you (using any number of inner communication or divination methods).

Pattern Literacy: Nature’s Archetypes

All druids seeking to wildcraft and connect deeply with the world around them would benefit from understanding what permaculturist Toby Hemingway called “Pattern literacy”. Patterns are nature’s archetypes; they are the ways that nature repeats itself over and over through broader designs, traits, configurations, features, or events. Each unique thing on this planet is often representing one or larger patterns. Learning pattern literacy is useful for all druids as a way of starting to engage with and develop wildcrafted druidries.

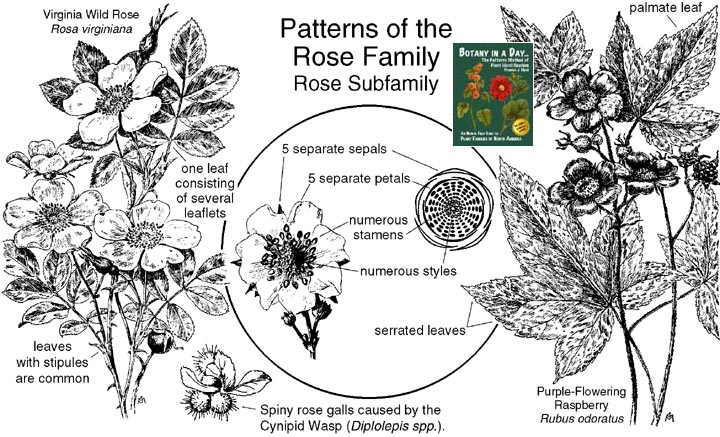

Let’s look at an example of pattern literacy from the plant kingdom to see how this works. The rose (Rosaceae) family is a very large family of plants and includes almost 5000 different species globally–including blackberries, apples, hawthorns, plums, rowans, and much more. Members of the rose family are found on nearly every continent in the world. Rose family plants have a number of common features, including five petals, five sepals, numerous stamens, and serrated leaves (often arranged in a spiral pattern). If you know this pattern, then even if you don’t know specific species in the ecosystem you are in, you can still do some broad identification–you can recognize a plant as being in the rose family, even if you don’t’ know the specific species. This information–along with lots more like it, comes from a book called Botany in a Day, which I highly recommend to anyone interested in learning plant patterns.

For those of you who are transient, traveling, or looking to connect to a new ecosystem, pattern literacy offers you a powerful way to form immediate connections in an unfamiliar ecosystem. Connections are formed through relationships, experiences, and knowledge–you can have a relationship with one species and transfer at least part of that connection to similar species in a new area. With pattern literacy, you can learn the broad patterns of nature and then apply them in specific ways to new areas where you are at. Once you can identify the larger patterns, you are not “lost” any longer, you are simply seeing how that familiar archetype manifests specifically in the place you are at. These kinds of immediate connections in an unfamiliar place can give you some “anchoring” in new places.

The best way to discover patterns is to get out in nature, observe, and interact. Reading books and learning more about nature’s common patterns can also help. In addition to Botany in a Day which I mentioned above, you might be interested in looking at Philip Ball’s series from Oxford University Press: Nature’s Patterns: A Tapestry in Three Parts. The three patterns that he covers are: Branches, Shapes, and Flow. Mushroom and plant books also often offer “keys” or key features that repeat over many plant families (e.g. shelf mushrooms, gilled mushrooms, boletes, agarics, etc). These kinds of books are other good sources of information. Learning nature is learning patterns–and pattern literacy is a critical tool for druids.

Recognizing the Uniqueness in the Landscape

Another useful way of wildcrafting your druidry is thinking about what is unique and special about your landscape. These can be natural features, beauty, diversity, insect life–and these unique features can be a land’s journey through history and restoration from adversity, the story of that land. Finding and connecting to these unique features may give you a way of seeing how your land is unique in a very local way. Some landscapes have old-growth trees, others huge cacti, others endless fields of flowers, and still others huge barren mountains with beautiful pigments. Each place is different, special, and unique.

For transient druids, traveling druids, or druids who are new to an ecosystem, recognizing the uniqueness in the landscape has added benefit. It allows you to focus on what is special and best about the landscape you are in rather than focusing on a landscape that you miss (e.g. being able to appreciate the prairie for what it is rather than focusing on the fact that there are few to no trees). Thus, this offers a way of orienting yourself in an unfamiliar environment.

Ready, Set, Wildcraft!

Hopefully, this post combined with my previous writings on this topic can help you develop a connection with your landscape, and thus, find new ways of deepening your wildcrafting practice. Find the cycles, find the patterns, discover what is unique, and discover what changes–all of these suggestions can help you better understand the world around you. If you have any strategies or ideas that weren’t shared here that have helped you wildcraft your druidry and connect with your local landscape, please feel free to share!

Reblogged this on Blue Dragon Journal.

Reblogged this on Paths I Walk.

Reblogged this on Good Witches Homestead.

I absolutely love your insight to the natural world of plant and earth energy!! I have a interesting question for you about black henbane. It’s not native to where I live at all, it’s been popping up all over the North east end of my city and getting closer and closer to my home; this makes me very excited for a variety of reasons but either way I’m absolutely fascinated by the natural spreading of this plant.

I don’t have black henbane growing here, so I’m not familar with it. So sorry I can’t be of more help! Blessings!

Thank you for this wonderful blog, Dana. I hear what you are saying… thank you. I think I am becoming more familiar with the Druidic way of being in the world, and it still seems that it is a perfect match for my way, except that i am one of those that is so far from the UK/Eurasian climate that I am still challenged by some aspects of living in a different Hemisphere to one that supports most of the Medic herbs I’m longing to grow. I’m a permaculture fan, incorporating those principles wherever I am able, and a bush regen-er as well. To that end I don’t have many exotic plants living here with me other than ‘weeds’ that were here before I arrived, new ‘weeds’ that appear every so often after a flood or drought, and those non-native plants that have huge merit as either food/shelter/wildlife habitat or Medic value which i’ve planted intentionally.. I’ve planted Elderberry, even though in some areas not too far away it is weedy.. but I will harvest flowers and fruit (I’d always leave some flowers!) so it shouldn’t escape too readily. …

I hear what you are saying… thank you. I think I am becoming more familiar with the Druidic way of being in the world, and it still seems that it is a perfect match for my way, except that i am one of those that is so far from the UK/Eurasian climate that I am still challenged by some aspects of living in a different Hemisphere to one that supports most of the Medic herbs I’m longing to grow. I’m a permaculture fan, incorporating those principles wherever I am able, and a bush regen-er as well. To that end I don’t have many exotic plants living here with me other than ‘weeds’ that were here before I arrived, new ‘weeds’ that appear every so often after a flood or drought, and those non-native plants that have huge merit as either food/shelter/wildlife habitat or Medic value which i’ve planted intentionally.. I’ve planted Elderberry, even though in some areas not too far away it is weedy.. but I will harvest flowers and fruit (I’d always leave some flowers!) so it shouldn’t escape too readily. …  I haven’t yet managed to adopt Hawthorn, although it is the chief medicine for my heart issues. I love that plant not only for its Medic value, but because of the energy of that plant, the atmosphere that it infuses into the surrounding area, as witnessed during an overseas adventure years ago.. Seeing a Hawthorn or yew very quickly became synonympus for me with ‘sacred place’. It is also very beautiful, and creatures will love it even if I do harvest the berries.. The term wildcrafting is one that appeals to me so powerfully, yet truly wildcrafting probably refers only to harvesting and creating with endemic plants etc, doesn’t it, or can that definition be extended to allow for these plants that came from elsewhere but now call this place home? They are all my friends, wherever they hail from.

I haven’t yet managed to adopt Hawthorn, although it is the chief medicine for my heart issues. I love that plant not only for its Medic value, but because of the energy of that plant, the atmosphere that it infuses into the surrounding area, as witnessed during an overseas adventure years ago.. Seeing a Hawthorn or yew very quickly became synonympus for me with ‘sacred place’. It is also very beautiful, and creatures will love it even if I do harvest the berries.. The term wildcrafting is one that appeals to me so powerfully, yet truly wildcrafting probably refers only to harvesting and creating with endemic plants etc, doesn’t it, or can that definition be extended to allow for these plants that came from elsewhere but now call this place home? They are all my friends, wherever they hail from.

Thank you for your always fascinating blogs and insights, Dana.

Thank you for your always fascinating blogs and insights, Dana.

Hello Shewhoflutesincaves!

Nice to hear from you! My belief about wildcrafting druidry is that it should be rooted in a local ecosystem, which would include anything that is present in that ecosystem. I don’t buy into the whole “native vs. invasive” binary (which is perpetuated by the chemical industry). Rather, I say, “what’s growing here and how can I build a sacred relationship with it?” Some of the best invasive plants are also the best edibles and medicine: Japanese knotweed being a great example. So to me, the origin is less important than presence. And YES on the hawthorn–some of the most powerful heart medicine on the planet! I hope this is helpful to you!

Blessings!

I was a druid once, long ago.

What is the druidic community currently doing to save the rivers?

Why is encouraging humanity to consume natural resources more important to your society then actually making sure we continue to have water available for our children?

The natural patterns of this planet have been altered since we began establishing the foundation of modern society in these lands. Our rivers are now dedicated to electricity to power blogs and social media. Every time anyone clicks a button, writes a post, advertises for a business, orders something like your book online or flips a lightswitch, that person is actively murdering our water supply. Yet, we waste clean drinking water to flush our own urine and feces down.

Loving nature, doing rituals, giving offerings, and reciting prayers, mantras, for the betterment of humanity etc does absolutely nothing when compared to the fact that all of our life is dependent on water. If you expect that a few prayers and rituals is equivalent to the amount of water an average human life wastes, I’m sorry, but nature would rather keep it’s water alive and functioning than have all the prayers in the world.

Maybe instead of telling people how to plant cute gardens, you could encourage more rain water collecting habits and more humanure techniques. Because your feces has more life producing content than your intentions do.

Hi Poop, Thanks for your comments. I get that you are angry and frustrated about the inaction of people globally. I am too.

This blog is one of the ways I respond to that, to try to help educate and teach others and lead by example. Since it is clear that you are not familiar with my body of work nor my own lifestyle, let me share: this blog has over 500 posts, many of them focused on both small and radical lifestyle changes and how we build a better world. My new book, Sacred Actions (https://thedruidsgarden.com/books/) which covers many topics designed to protect the waterways including humanure and water reduction. That book is full of suggestions for regenerative living, to help people transition from waste-driven activity to care-centered and earth-honoring activity. Everything in this book is what I live and how I live. These include all of the things you suggest: honoring humanure and liquid gold, rainwater collection (as well as other water-saving activities, like swales) and a bunch of other stuff. I work locally here to protect and heal our waterways, including the 2500+ miles of streams dealing with Acid Mine Drainage. My home is powered by solar, not coal or hydroelectric. I practice humanure and composting my own waste, see this post: https://druidgarden.wordpress.com/2017/01/01/embracing-the-bucket-a-colorful-compost-toilet-for-small-space-living/. I live 100% everything that I share on this blog and in this book. It’s easy to point fingers, and it’s hard to make lifestyle changes and actually live in line with nature.

Now here’s where you and I differ. I believe in the power of ritual and ceremony; as the old adage goes, “as above, so below; as within, so without.” I understand that as a civilization and a world, we face grave challenges, challenges that seem insurmountable. Beyond doing my own part and encouraging others to do theirs, the earth needs our prayers, our ceremonies, and our kind attention. It needs us to be there for it, both physically and energetically. I’m in good company, as people all over the world in all kinds of traditions, including those from indigenous backgrounds that are very earth-aligned, believe and do the same thing. In some cases, people believe we are well beyond the tipping point–and if that’s the case, then ceremony and prayer is one of the few effective avenues we have left.

This is about SO much more than cute gardens. A garden is a good place for people to start to reconnect. It’s a helpful gateway into much more dedicated regenerative and sustainable living practice. But ultimately, we are talking about all of us making radical lifestyle changes and changing the nature of our cultures and civilization. And in the meantime, we can all do as much ceremony as we can on behalf of the world.