I’ve been spending a lot of time talking about various wild foods and other kinds of wildcrafting and foraging on this blog, and I wanted to talk today about the principles of wildcrafting and ethical foraging more broadly. This post is the first in a series of two that focuses on introducing the reader to how to effectively wildcraft/forage, and is built upon my extensive experiences foraging and wildcrafting, which I have been doing in some form since childhood, but which I took up quite seriously about 7 years ago. This post offers definitions, supply lists, resources, what and how to learn, and information on timing. My second post in this series will discuss locations, avoiding environmental pollutants, and ethics. Also please note that this is an older post–see an updated discussion of foraging here!

Defining Wildcrafting and Foraging

Defining Wildcrafting: Wildcrafting is a modern term for an ancient practice. For as long as humanity has existed, we have gathered from the natural world for our food, shelter, medicine, clothing, ritual items, arts, and much more. Wildcrafting today refers to gathering materials from the land that you will use for various purposes, most frequently food or medicine, crafts, household items, natural building, carpentry, ritual items, clothing, and more. I often see the term associated with medicinal herbs, but there are many other possibilities for the wildcrafter. Non-food uses of wildcrafted items that I’ve covered in this blog include wildcrafted medicines such as jewelweed salve or various medicinal tinctures, smudge sticks, inks, baskets, and incense.

Defining Foraging: Foraging is a type of wildcrafting that is specific to finding food: wild food foragers hunt for food throughout the year (and I’ve covered many of my favorite foods one can forage for: burdock, black raspberries, violets, ramps, chicken of the woods mushrooms, and autumn olives, to name a few).

Other associated terms you might hear are bushcraft (a term for a variety of wilderness skills, such as shelter building, trapping, or fire making) and woodcraft (another term for skills associated with the woods).

Why Wildcrafting/Foraging?

This is a good question, and one that I get asked more often than one might expect. For me, wildcrafting and foraging have numerous benefits, many of which are not material. First, as a druid, I enjoy spending time in nature, in stillness, in focus, and simply enjoying the natural world around me. Wildcrafting gives me a good reason to get myself into the forest and the fields as often as I can. Second, I’ve been talking a lot on this blog lately about reskilling; developing the skills necessary to transition to a sustainable and earth-centered future. Learning once again to live off of the land, to live in harmony with the land, and to take only what is necessary is an important part of that path. This is what our ancestors did–and this is what we will again do–if we can learn to do it correctly and in balance. Third, I really enjoy the tangible benefits–the medicine, the food, the various craft items. I have tasted more new things and have been able to heal myself right from the land around me–these are empowering things.

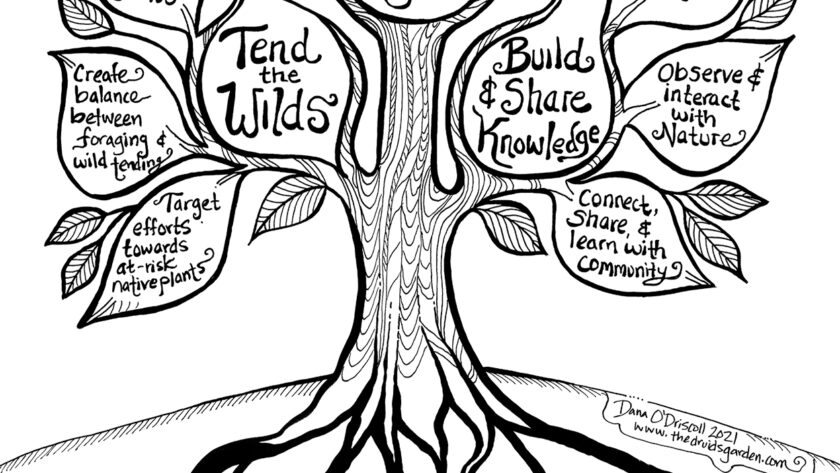

Knowledge is critical to this path. Not only knowledge of what you can take and use, but also knowledge of how that taking impacts the ecosystem. An ethical forager is a knowledgeable one, connected to the land, and knowing their impacts. So throughout these two posts, I’m really going to stress that you need the knowledge to do this effectively.

Wildcrafting Supplies

Compiling some basic supplies will allow you to make numerous successful excursions. Over the years, I’ve compiled the following supplies, which are useful and necessary:

Foraging Bookbag. When I got out foraging, I have a special “foraging” bookbag that I take with me with some basic supplies that are useful for finding food, medicine, and other kinds of things. The bag was one I purchased at a yard sale for 50 cents; it needed some minor repairs but works great.

- Essentials that are always in the bag include sunscreen, an essential-oil based bug spray, fire starting equipment, an energy bar, a can of pepper spray, a hat that easily folds up, a compass, fire-starting equipment, and basic first-aid supplies. I also bring water; usually I don’t bring much in the way of snacks because I can always find a few trailside nibbles (that is, unless I will be out for some time and then I will bring some other stuff).

- Tools: The Hori Hori. If you are only going to have one foraging tool-this should be it. Its a Japanese gardening tool that has a serrated edge, a sharp edge, and can dig and cut. I won’t leave the house without it! I purchased mine for $30 and its one of the best purchases I’ve ever made.

- Other Tools in the bag include a small hand saw that folds up to about 7″ in length; my hori hori of course, a pair of scissors, a smaller knife, and a pair of gloves. These are all fairly light. If I’m going out for roots or tubers (like cattail, ground nut, or burdock), I might take a long a little fold-up shovel or even a garden fork if I’m not going far, but those are quite heavy, and I add these only when I need them. The knives are for cutting various plant matter or mushrooms; the hori hori can be used for cutting and also be used for digging roots or limited sawing. The hand saw is for getting branches or barks (useful to cut up roots from a fallen sassafras tree, for example). The scissors are good for harvesting smaller plants or greens, such as yarrow or nettle. I usually use the gloves for harvesting stinging nettles, which I take every opportunity to get when I go out in the summer.

- Storage. The foraging bag also holds many different kinds of smaller bags for bringing things home–a few larger canvas bags for nuts or mushrooms, a few mesh orange/lemon bags (particularly good for mushrooms because it allows them to breathe), plastic bags of various sizes that I re-use, and paper bags of various sizes. I keep all of these materials in the bag and then when I want to go out (usually at least twice a week in the summer).

- Blickeys. If I’m going berry picking specifically, I may also bring a blickey or two (see photo), which can be created from a gallon plastic jug. You just cut part of the top off of the jug, so you can easy place things in. You leave the handle intact, which can go around your belt. They are super lightweight and free to make. If you don’t drink anything that would have them, a quick trip down your road on recycling day is sure to procure an abundant supply. Because I have a friend with a severe dairy allergy that I often share wild-harvested treats with, I only use ones that had water or apple cider (like the one pictured), not milk. So keep that in mind when making your blickey.

The blickey–fantastic for gathering nuts, berries, or flowers, repurposed and recycled

Clothing for Foraging. I also always make sure I am wearing long pants and a belt; sometimes I will also include a hat for the sun and my muck boots if I am going into swampy areas. Long pants are a great idea year-round–in the summer they can protect you from poison ivy (even the most experienced wildcrafter sometimes wanders into a patch unawares–like the time I was enthusiastically harvesting St. johns wort and realized that underneath the top layer of plants, there was a lower layer of poison ivy–thank goodness for the jeans and muck boots!) For shoes I will wear hiking boots or muck boots (the muck boots are really hot in the summer). The belt can hold a blickey or my Hori Hori or both.

Company for Foraging. I have found that foraging is much more fun with a friend than by one’s self. If I mention to some people that I’m heading out for a few hours, I almost always can find someone who wants to come with me and see what’s out there.

Other Resources. I usually take one or two field guides with me (see the next section for ideas), depending on what I’m going for. Since I’m still learning mushrooms, in the last two years, I was usually carrying a compact mushroom guide and one or two other books, depending on the time of year and what I’m looking for. I often bring more books and leave them in the car, such as Matthew Wood’s Earthwise Herbals. Field guides are particularly useful for plant ID. What’s Doing the Blooming has traveled with me far and wide.

Resources/Books for Wildcrafting

These are resources specific to the Midwest and Northeast Regions–if you are in another region, I’m sure there are other good guides for you to find (and a local forager friend could be of help here!)

Understanding Ecology. John Eastman has written a really good series of books on the place of many plants and trees in the ecosystem; and I highly recommend these works to anyone who wants to learn how to forage ethically and responsibly. Why? Because if we are going to take, we need to understand what we are taking and how what we take fits into the ecological system–what insects or animals depend on the plant, what other plants are typically found in the area, and so on. This is knowledge that our human ancestors intimately knew, and if we are going to engage in these kinds of activities, we too must understand it, first and foremost. The three books I’ve read from cover to cover that provide this information are: The Book of Forest and Thicket, The Book of Swamp and Bog, and the Book of Field and Stream (they are the three tan/white books in the front of the photo). Honestly, this is a good place to start even before you begin gathering anything.

Wild Foods. If you are going to be looking for wild foods, I recommend Sam Thayer’s books: The Forager’s Harvest and Nature’s Garden. They are both available from his website (he self-published them, and they are the best foraging books I’ve ever read). I often have them with me out in the field and I study them when I’m not out and about.

General Plant ID. For flowers, there is a great and compact book called What’s Doing the Blooming? and its super useful for all manner of blooming plants (good for wild food, medicine, and even dye plants). Blooming plants are often fruiting plants later in the year, so you can identify them early in the season using this. Otherwise, any field guide with photos should be sufficient–there are some produced by the Arbor Day foundation on trees that are also useful.

Medicinal Plants. I took a four-season herbal intensive with Jim McDonald and that’s how I learned to ID many plants. I combined this with Matthew Wood’s two volumes, The Earthwise Herbal (vol 1 and 2). Usually if I need to find a specific plant, I’ll study it before I leave the house, locate it in one of my field guides, and then try to find it when I’m out.

Dyes. There are numerous dye books and mushroom dye books that are also useful if you are going that route. Some that I like are: Dean and Cassleman’s Wild Color and Bessette and Bessette’s A Rainbow Beneath My Feet: A Mushroom Dyer’s Field Guide.

Native American food/medicine/craft books. Some native American books that cover medicinal or edibles are really useful in terms of recipes and information. I have a few out-of-print ones on my shelves, and they have taught me much about traditional uses (such as hemlock-hickory tea and how to make pemmican!)

Other crafts: What you are looking for is very dependent on the craft. Books on basketweaving and natural weaving will describe what to get for those crafts; pine-needle basketry will obviously be about pines, and so on. Natural papermaking books will obviously teach you about what to gather for that (I have a few posts on natural papermaking as well). I haven’t found good books on foraging for incense supplies, but I do have some information on my blog here, here, here, and here about it. My post on smudge sticks perhaps is the most comprehensive in terms of wild plants you can burn that smell good (never fear! I am working on a much longer post on that subject in this upcoming year–still testing plants at this point!)

How to Build Knowledge

Only some of my knowledge on this subject came out of books. A lot of it came from learning from others–I walked at my grandfather’s side and later, my uncle’s side and they taught me much about plants as a child. Much later, I attended a full year of my friend Mark’s “Eat Here Now” classes where he did a monthly plant walk at various locations. I attended several mushroom hunting workshops to learn the mushrooms (and would like to attend more). And of course, I attended my four-season herbal intensive (which included one day per month of plant walks out in the field). I also went out with others who knew different kinds of things and we learned from each other. I talk to people about plants often–and am always ready to learn something new or teach someone else.

I have found that focusing your energies on one area can lead you to success and allow you to, over time, build a very diverse set of knowledge about things you can wildcraft. Now, when I got into the woods, I am ready for anything–crafting supplies, dye plants, medicine, wild snacks, and treats, wood to carve, and much more. I focused my energies each year on learning a different set of things and adding to my repertoire–the first year, it was mainly art supplies and incense making–I gathered resins and found every berry I could and tested its dye and ink capacity. The second and third years, I focused on learning all of the wild foods I could and kept looking for dye plants and such. The fourth year, I focused on wild mushrooms and brewing, in addition to food and craft/dyes. Finally, this year, I added medicinal herbs (and will probably continue to focus on them for some time). I made it a point to go out into the field at least six times a month looking for what I was looking for and also paid attention to what was already growing at my homestead.

Its also a good idea to learn characteristics of plant families — the book called Botany For Gardeners, recommended to me by Karen (one of the frequent readers and commenters on this blog–thanks Karen!) can really be of assistance. This way, you can begin to identify plant families and even if you find a plant you don’t know, its features will give you some clue as to other related plants.

A final point about building knowledge–one of the first things you should learn is what can cause you harm. I think first-time foragers should all learn to identify poison hemlock in ALL of its stages before anything else. Poison ivy gets a lot of notoriety, and frankly, can give you a bad rash and a few unpleasant weeks. But Poison Hemlock WILL KILL YOU if ingested–and it has many lookalikes in the Apiaceae family (such as Queen Anne’s lace/Wild carrot). Even just touching or smelling Poison Hemlock can cause nausea, dizziness, and disorientation. Recently, I was officiating at a friend’s wedding. The bridal party was getting ready to pose for photos along a bridge on a trail. I saw a huge patch of it right where people were standing and watched someone reaching down to touch it (it was pretty, in full bloom). I quickly pointed it out and had everyone move to give it the respect it was due. Interestingly enough, a few months later, one of the people in the bridal party reached out to me to learn more about this plant and many others. Other plants I would learn quickly include the death angel/avenging angel mushroom, poison sumac, and poison oak. When you start looking for particular plants, also be aware of what plants may look similar to the plant you want ( a good foraging book, like Sam Thayer’s books, will teach you this).

What You can Wildcraft and Setting intentions

Truthfully, the better question is–what can’t you wildcraft? I’ve taken particular joy in learning as much as I can about as many plants as possible and their uses. For example, see my extended post on the dandelion. One of the things you want to ask yourself is–why are you wildcrafting? For medicine? For Food? For crafting? This will determine, to a large extent, what you are looking for and what resources you will need. You also want to consider the abundance of the plant and who else may be depending on the plant as a food source (more on this in Part II of this series).

Setting your intent: Wandering vs. Targeted Harvesting. Sometimes I go out wandering to see what I can find, while other times, I have a very specific harvest in mind. Determining this will indicate where I should go (e.g. a few days after a “weather event” to look for mushrooms; to the outskirts of a housing development to pick serviceberries, and so on). If I don’t have anything in mind, I will go to one of several wild areas and make it a point to return to the same area at multiple points in the season to gauge how the crops are progressing.

When you are first learning, the other thing is that you might not know where to get certain things. These “wanderings” then, while time-consuming, are wonderful times of discovery. They help you establish your “spots” for future harvests–look for abandoned apple orchards, berry patches, abundant fields, and so much more.

Keeping records. I keep fairly detailed records of harvests and locations. I know others who draw extensive maps so that they can find their mushrooms again the following year. All of this is useful as you are learning–looking at your records from one year can help you figure out the locations and timing of where you want to go.

Wildcrafting Timing

Timing is a tricky thing in wildcrafting. Generally, the more often you go out, and the more time you devote, the more impressive harvests you will find. Each year can be its own wonky thing, and you can never be sure that the wild blueberries will be blooming at the same time (they, like everything else, can often vary by several weeks depending on the weather) I find it better to visit early in the season and stop back often for things you really like than to miss the harvest entirely. For example, as I mentioned in my dandelion post, each year there are about 7-10 days of “peak dandelions” where they are blooming and abundant–and this is really the only time to make wine because its the only time they will be in the volume you need. If you miss the harvest–you’ll have to wait till the following season.

The other important thing about timing is that not everything is abundant each year. This is why we must take advantage of harvests when we find them and understand how to stretch those harvests out in times of scarcity. I remember, for example, the great apple harvest of 2013; the great st. john’s wort harvest of 2014, and the great berry harvest of 2011 and 2013 (and the lack of any berries to speak of in 2012 and 2014!) Canning, drying, freezing, and other forms of preservation can allow us to enjoy the bounty even in years of famine. A lot of people, as i mentioned in my earlier post, don’t really understand this. The supermarket is always abundant, and if you are going to share wild foods with them, I would suggest making them come with you on a trip or two so that they understand the work of it–and also the joy.

Stay tuned for my second post next week, where we’ll delve into understanding the ethics of foraging, discussing where to harvest safely, and more!

Excellent Article!!!

Thanks Linda! 🙂

One of my most favorite topics and activities. Invite me whenever you’d like! 🙂

Will do, Elissa! 🙂

Reblogged this on Fairy faith in the Northwest and commented:

awesome stuff!

You’re welcome! 🙂 Although you might be thinking of a different book. I don’t think there’s much about plant families in Botany for Gardeners.

I often end up wandering into the woods with no equipment at all, and if I find edible mushrooms, I cut them with my car key and bring them back in my hat. That is, a beginner may not need to worry much about having particular equipment before getting started.

Reblogged this on Mystic Grove and commented:

Great blog full of wonderful information

Thank you so much! 🙂

So helpful. I am currently taking a Master Herbalist Program and feel stuck because I’m truly a beginner! This has helped me confirm I need to connect with some veterans in this craft! Thank you!

Glad it was useful to you :). What herbalism program are you taking?

[…] really enjoy foraging for foods in urban environments, you just never know what you are going to find. In the spring, […]

Reblogged this on Rattiesforeverworldpresscom.